I looked up to meet the doctor’s eyes. I knew the question before she asked. Suddenly, I became hyper-aware of the overpowering smell of disinfectant, coating every surface of the emergency room.

“Have you been eating?”

I lied, obviously. Any lie comes easy if you repeat enough, and easier once you believe it. But draped in a hospital gown, the lie tasted bitter.

I realized it was the first time I had tasted anything in a long time.

More than 91 percent of women in the United States are unhappy with their bodies. Magazine covers gleam with dieting tricks and exercise routines, playing on the accurate assumption that these concerns plague nearly every woman.

On a college campus, the compounded effects of academic stress and constant comparison with peers only amplify the issue of body insecurity.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders identifies three major eating disorders: anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. U.S. prevalence rates are 0.3 percent, 1 percent and 3 percent, respectively.

According to the 2015 National College Health Assessment report, 0.6 percent of University of Wisconsin students have been diagnosed with, or sought treatment, for anorexia — twice the national average.

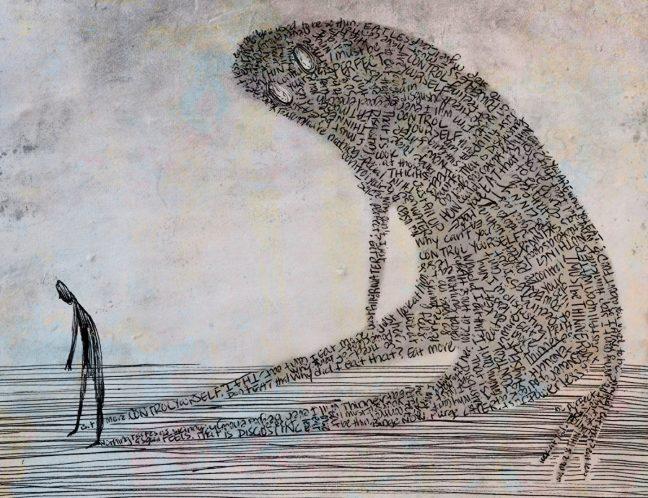

But statistics fail to reflect the magnitude of body hate, disordered eating, fat talk and insecurity pulsing in the veins of a college campus. This story remains untold by aggregate data. It is silent suffering. It is unbearably painful.

Seeds of insecurity planted at a young age

UW senior Andrea Collins, a psychology major, recalls her earliest memory of disordered thoughts and eating in fourth grade.

“I can’t remember a time I was comfortable with my body. I had friends who I thought were way prettier and skinnier than I ever would be,” Collins said. “The first day I starved myself, I called them to proudly claim I ate nothing but a granola bar.”

Collins’ experience is consistent with the profile of most eating disorders. Some people are already genetically susceptible, and environmental factors — such as the media — begin to have an effect at a young age, UW psychology assistant professor and researcher James Li said.

The distressing reality is that by the time many girls begin to understand their bodies, they have begun to criticize their bodies, UW senior Bridget Sicard said.

For UW alumna Emily Rhodes, the trauma of losing a parent triggered already aggressive dangerous, distorted thoughts.

“I was in second grade, keeping a diary of my weight and what I ate,” Rhodes said. “In my life, I have never had a good body image.”

Andrea Lawson, co-director of mental health services at UHS, said disordered eating often starts as a coping mechanism to manage stress or family issues.

“During a major transition, a switch gets flipped, and it turns into an eating disorder you no longer have control over,” Lawson said. “And college campuses are prime for that.”

Arrival to campus can be the trigger

Upon arriving at UW, Sicard navigated campus as if wearing a radar.

“I would compare myself to every single girl that walked by me on the street — ‘what do her legs, arms, butt look like?’ — and I would compare it to myself. I ran through this every day. It consumed my thoughts,” Sicard said.

The 2015 Healthy Minds survey, conducted nationwide, found 19.7 percent of UW students screen positively for an eating disorder. Put another way, Lawson said, if you know five students on campus, you know one who screens positive for an eating disorder.

A positive screen for an eating disorder does not imply diagnosis, but a heightened risk for dangerous behaviors.

Comparison and competition are defining features of the campus setting, Lawson said. In addition, extreme behaviors from drinking, to sleeping, to eating, to exercise become normalized.

“At their core, campuses are so competitive in so many different realms. There are measurable ones, like grades, athletics, internship experience,” Collins said. “But there are also those you can’t measure past your own perception, and body image is one of those things.”

After struggling with disordered thoughts and behaviors throughout high school, Sicard found herself immersed in this atmosphere. Terrorized by the “freshman 15,” she lost her sense of control, and began binging.

Chanda Bolander, coordinator of Eating Disorder Services at UHS, said fear of the “freshman 15” causes a heightened anxiety that can turn into an eating disorder.

But this fear is rooted in myth. Numerous studies on health and bodies have repeatedly found the “freshman 15” is nothing more than a parable, Lawson said. Average weight change is around five pounds — normal for freshmen-aged women who are still going through puberty.

But some still experience body hate, regardless of the number on the scale. UW senior Jeung Bok Holmquist, a film major, said entering college transformed their obsession with weight to an obsession with appearance.

“The body dysmorphia was constant,” Holmquist said. “I was delusional, convinced I was truly overweight when I truly was not.”

Body dysmorphic disorder is a body image disorder characterized by persistent, intrusive preoccupations with an imagined deficit in one’s appearance. While not necessarily linked to weight, BDD often occurs with eating disorders.

And for someone with very low body image, at high risk for developing BDD, the campus environment can be the trigger.

UW junior Kyra, who asked to be identified by her first name only, was diagnosed with anorexia nervosa in seventh grade. She spent six months in treatment prior to college before dropping her weight once again during her first semester.

From living in a dorm to rushing a sorority, being exposed to people who all seemed happy and beautiful was overwhelming, Kyra said. And post-anorexia treatment, many people develop bulimic tendencies.

“Living in a dorm, sharing bathrooms, sometimes deterred my behavior,” Kyra said. “But so often, you overhear someone judging another person as fat or ugly … It was very triggering. I felt I could be that girl they were talking about.”

Campus atmosphere can exacerbate body hate

A range of factors, including stress and isolation, make college campuses a hotbed for several mental health issues, said Sandra Eugster, founder of Westside Psychotherapy outpatient clinic in Madison.

“If you’re not told your cognitions are distorted or your behavior is concerning, then in the college setting, body expectations overshadow more rational thoughts about appropriate exercising and eating,” Lawson said.

Will Cox, assistant scientist in the psychology department, studies the effects of fat-shaming. On campus, while fat-shaming may not be overt, a serious concern is “fat-talk” among peers.

“We have young women who get together — each girl talks casually about how fat she thinks she, but it actually has negative effects on [the others],” Cox said. “The way you talk about yourself affects how others feel about themselves.”

Women are used to talking poorly about themselves, and it’s highly contagious, Sicard said.

This also heightens risk for social reinforcement of dangerous behavior. Girls often severely restrict intake before a night of drinking to save calories, exercise serves as punishment for unhealthy eating and fashion choices become driven by how clothes reflect body weight rather than aesthetic preference.

The strain on women to appear as thin as possible also stems from the uninvited, persistent hyper-sexualization of the female body, Kyra said. The worthiness of a woman, so deeply intertwined with her desirability, leaves girls feeling pathetic or irrelevant if they aren’t “sexy.”

While men are not subject to the same standards, they aren’t immune to body insecurity and disordered eating. UW senior Matt Grande, a psychology major, struggled with body image throughout high school, and has engaged in restrictive behaviors during college.

For men, the pressure is not to be skinny, but the polar opposite, Grande said. The male narrative is centered around exercise. Instead of expressing their insecurities, men become obsessed with working out.

“I know men experience it, but we never talk about it,” Grande said.

Body insecurities don’t discriminate

For marginalized students, body shape becomes yet another dimension on which they don’t belong.

The alienation minority students already face because of their identities can elevate the risk of body hate, UW sophomore Saja Bilasan, who is majoring in psychology and gender and women’s studies, said.

Bilasan, who identifies as Arab, said her body image challenges intensified in college, where she began a pattern of restrictive eating and binging.

“The lack of body diversity is the main problem. I see so many girls here with the same body type and it’s the one associated with being beautiful,” Bilasan said. “Too many body positivity campaigns all center on white women.”

As a result, it can still feel like there is no right way for a woman of color to have a body, Bilasan said.

Holmquist, who is Japanese, describes their standard experience scanning a lecture hall — an experience shared with many students of color at UW.

“You sit in a 100-person lecture and you see all these skinny, white girls with the same clothes, the same body … and you realize, I will forever not look like them,” Holmquist said.

While eating disorders have been historically perceived as a plight for white women, Bolanger said the demographic picture of UW students seeking treatment from UHS confirms eating disorders do not discriminate. Eating disorders are not gender-specific, she said, nor do they vary by race or class.

UW senior Sam*, who identifies as a gay man, found that coming out in college exacerbated pressure to fit a certain body type. The societal expectation is that gay men are skinny, Sam said. But striking that balance between “not-too-muscular” and “not-too-scrawny” is near-impossible.

But the LGBTQ+ community can also be a protective factor. This was the case for Holmquist, when they transitioned to identifying as non-binary.

“The gay women I hang out with are so loving, accepting of their bodies,” Holmquist said. “I think we’ve unlearned some of what straight women are taught, which hinges on obsession with male gaze.”

Unfortunately, not all students have the support of family or community, UW alumna Ameerah*, said. As a Muslim and first-generation American, she knew discussing this incredibly stigmatized disorder with parents would only catalyze arguments and denial.

Removing barriers to access in treatment

The tremendous stigma and shame associated with eating disorders contributes to what Eugster sees as a real disparity between eating disorder statistics and reality.

Most people suffering from eating disorders or disordered eating are not seeking treatment, which makes it increasingly difficult to understand the magnitude of the problem, Eugster said.

The complexity with eating disorders is how easily they can manipulate the mind into believing these are healthy, goal-achieving mechanisms, since they are very functional in the short-term. In reality, Lawson said, an eating disorder is a separate part of you, sabotaging your goals and identity.

“The difficulty is pulling the two apart — what is me, and what is my eating disorder,” Lawson said.

An additional danger is the large subset of students on campus who don’t seek treatment because they don’t meet the criteria for the disorders, but continue harming themselves.

And waiting for symptoms to appear before seeking help can be deadly. UW junior, math and geography major Claire, who chose to be identified by her first name only, recalls distress when she experienced amenorrhea, the loss of menstruation diagnosed in anorexic patients.

“I remember thinking, ‘I started this because I wanted to be healthy, and now I’m not sure I can have a child’,” Claire said.

To serve this population, eating disorder treatment at UHS is not exclusively administered to students who are diagnosed with an eating disorder, Bolanger said. People don’t always fit into the boxes built by DSM criteria.

Treatment starts with a phone call discussing symptoms and service options. UHS offers individual counseling, brief treatment and group therapy, Lawson said. Group therapy can be especially helpful since eating disorders are “disorders of secrecy.” It can be helpful to talk to others who have experienced the same thing.

But for Rhodes, the fear of not being taken seriously prevented her from utilizing group therapy offered by UHS.

“I went to UHS and they offered group therapy, but I didn’t want to do that,” Rhodes said. “I feared I’d walk in, and I’m not really small, so people would think I didn’t really have a problem.”

While UHS can offer services within its scope, patients requiring more intensive therapy are referred to outpatient clinics, like Westside, where Eugster approximates nearly 30 percent of clientele are UW students. Full-blown anorexia is not so common, but there are a huge number of women hyper-exercising and under-eating, Eugster said.

This is consistent with the narrative of many UW students, who are restricting, binging and purging without diagnosis, but require treatment nonetheless.

Kyra, still in the process of recovery, believes prevention efforts are critical. Restrictive behaviors are reversible, but the firm grasp of negative thoughts, even after treating the behavioral component, is powerful.

Recovery is a jagged road

Recovery requires nourishment, Li said.

The effects of being undernourished mirror exhaustion. The daily rigors of life and difficulty concentrating or handling stress, paired with the disordered cognitions consuming the mind, put the body in a state of weakness which is unreceptive to therapy, Li said.

But after restoring the body, recovery of the mind is possible.

“I would sit down with another chair in front of me and talk to my eating disorder,” Collins said. “I needed to tell myself it was not a part of me and I could overcome it, with an action plan.”

When it comes to awareness, a general sense that many classmates also feel insecure about their bodies is inadequate, Collins said. Complacency and acceptance that body hate and restrictive eating are simply part of the college experience fuel the continuation of this epidemic.

“The university should be talking about this to freshman,” Kyra said. “We talk about sexual assault and substance abuse, and these dangerous behaviors are happening on a similar level.”

For Sicard, and the many others on campus who share her experience, eventually realizing that she had control over nothing but treating herself with love ultimately began her healing process.

Recovery is a lifestyle, not a destination. Inevitable ups and downs, relapses and moments of weakness do not negate progress.

“We all come in different bodies, and there is so much beauty in each body we don’t appreciate,” Bilasan said. “Learning to appreciate my own individuality definitely helped me. That’s what healed me.”

***

If you are concerned about your eating behaviors, or those of someone you care about, please visit UHS for support.

*Names have been changed to protect the privacy of some sources who have experienced eating disorders.