As topics like obesity, climate change and stem cell research increasingly stir up heated debates among Americans, one University of Wisconsin professor questions whether there may be a growing anti-science sentiment in the U.S.

Dietram Scheufele, UW professor of life sciences communication, delved into the question of American anti-science sentiment at a “Crossroads of Ideas” lecture Tuesday at the Morgridge Institute for Research. He said it’s not necessarily that Americans deny science, but their personal values and political alignments strongly influence what information they accept.

Scheufele said this is due in part to the idea that Americans live in “tribes.” Homophily, the concept that Americans mostly interact with people who are just like them reinforces what they know, don’t know and what they refuse to know.

Tribes can refer to a group of people who share any kind of similar beliefs, but the most dominant in the U.S. revolve around religious and political ideologies, he said.

“We’re a deeply religious country,” Scheufele said. “That’s not good or bad, or right or wrong, but it’s a reality in terms of how we communicate science and ultimately, how we think about science.”

A survey by the National Research Council shows the way science questions are worded can have a big impact on how Americans might receive them. For example, a question asking whether astronomers believe the universe began with a big explosion is more likely to have Americans respond yes than a question that asks Americans whether the universe began with a big explosion.

Americans align themselves closely with people who share similar beliefs — religious or otherwise, Scheufele said. It restricts their social worlds and essentially allows them to tune out any information they don’t want to hear, he said.

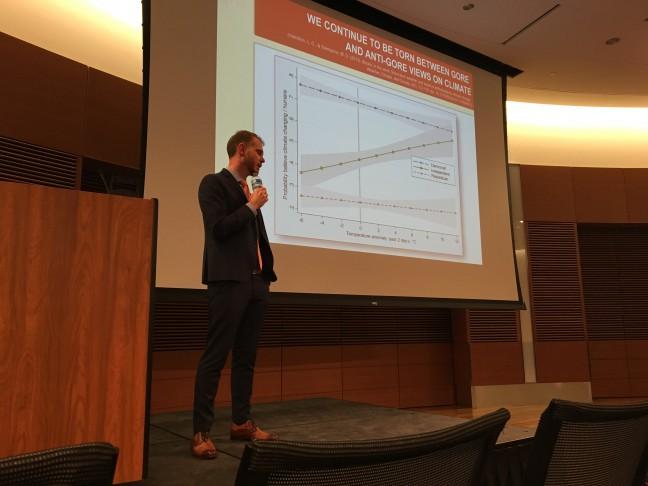

Tribe separation is especially evident in politics, as Democrats and Republicans are ideologically far more polarized today than they were in the past, Sheufele said.

According to a Pew Research Center study, 27 percent of Democrats think Republicans are a threat to the nation’s well-being, while 36 percent of Republicans think that Democrats are a threat.

“It’s not just that we disagree, it’s that we hold unfavorable views,” Scheufele said.

The rapidly changing media landscape is partially responsible for this, Scheufele said. According to talk show host Rachel Maddow, “opinion-driven media makes the money that politically neutral media loses.” As consumers of this system, audiences only encounter what they already know or want to know, he said.

In the end, public perception depends on the way messages are relayed. Some think sound science will speak for itself — but that has proven not to be the case. The solution is about outcomes and values, Scheufele said.

For example, he said it’s more effective to focus on things like global competitiveness and energy independence than combatting climate change when talking about green energy. Neither “tribe” has to be right or wrong, conversations about science prove to be much more effective.

“Slicing up the audience by interest makes a lot of commercial sense,” Scheufele said. “But it’s particularly problematic because the social environment in the tribe which we think we belong to really shapes how we act and how we behave.”