Former University of Wisconsin doctoral student Yeaji Kim developed the universal system Tactile Stave Notation to create better sheet music for blind and visually impaired musicians.

Tactile Stave Notation allows students to feel the same symbols and notations their teacher is seeing, bridging the gap that braille posed between a teacher and their blind student, UW professor of piano and piano pedagogy Jessica Johnson said.

Kim, who struggles with musical literacy as a blind musician, found that braille was an extremely complex and daunting way for new musicians to read music, Johnson said. Kim came up with Tactile Stave Notation with the hope of creating an easier way for the visually impaired to study music.

A major obstacle is finding teachers to work with the visually impaired. With this system, teachers won’t have to learn braille to teach their students.

“This system is incredibly innovative,” Johnson said. “The potential impact on the way music is studied [and] learned as well as the way that it will allow more people access to diverse types of music is very exciting.”

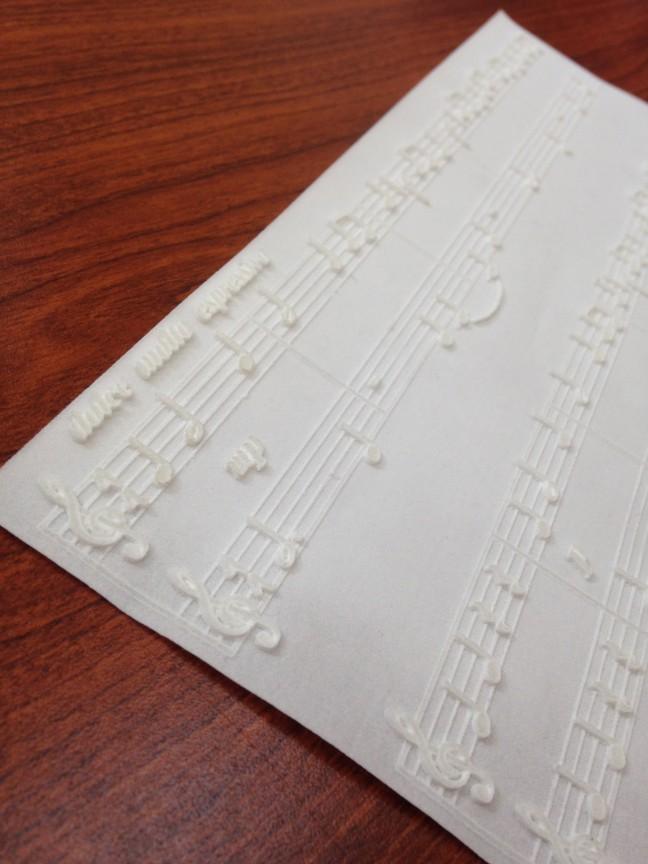

To create this notation they use a selective laser-sintering machine, one of the most advanced technologies that exist for 3D printing, William Aquite, a research associate in the department of mechanical engineering, said.

This machine puts down a layer of powder on a printing bed and a laser selectively melts certain sections, sintering two layers, meaning they are partially attached, which allows for the score to be depicted on different layers.

Working these powders poses a challenge though, as there is a possibility of both shrinking and warping in the process after they heat up and cool down, Aquite said.

“The main advantage of this process is the resolution you can get,” Aquite said. “The resolution you can achieve is one-four-thousandth of an inch so it is very high accuracy.”

Johnson said there is no system in existence like Kim’s for music notation.

Johnson said Kim felt she didn’t have all the information that the composer intended, making her reliant on the teacher.

“This motivated her to develop an alternative notation system that would be accessible and facilitate better communication between visually impaired musicians and their teachers,” she said.

Kim returned to South Korea last year, but has continued her collaboration with UW engineers to further improve the notation. Aquite said he sends prototypes to Kim who emails feedback as they continue to adjust the notation to find the most readable form.

Engineers working on this project have tried to predict at what stages there will be changes and then use reverse engineering to correct them. Aquite said accuracy in this process is imperative not only so Kim can feel the notation, but so she doesn’t cut her fingers on residual powder.

With no software or programming available to translate a sheet music into 3D print, every detail in the process matters as engineers adjust different levels and sharpness of corners to create the most readable notation, Aquite said. Being an experienced musician, Kim is much more sensitive to touch than a younger student.

Aquite said they are still working on finding the correct resolution.