Researchers at the University of Wisconsin are taking part in a new study funded by the National Institute of Health examining the development of Alzheimer’s disease in people with Down syndrome.

The study focuses on people with Down syndrome because they are at a high risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease.

One of the co-researchers of the study, Sigan Hartley, is a Waisman Center investigator and a professor of human development and family studies at UW.

AstraZeneca resumes COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial on UW campus

“We know that this is a condition that can affect anyone in the general population,” Hartley said. “We now know as a research community that adults with Down syndrome have an increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease.”

People with Down syndrome have three copies of chromosome 21 — one extra copy compared to the general population. This extra copy of chromosome 21 causes phenotypic differences and intellectual disability ranging from mild to moderate, according to Hartley.

Waisman Center Associate Director Bradley Christian is a co-director of the national study and leader of the UW research team.

According to Christian, the prevalence of Alzheimer’s in people with Down syndrome was only noticed within the last several decades, as there was a dramatic increase in the life expectancy of people with Down syndrome.

Christian said this increase is due to the many recent improvements in healthcare for individuals with Down syndrome, which allowed them to live longer.

“But because of having three copies of chromosome 21, [people with Down syndrome] also will virtually develop the brain neuropathology of Alzheimer’s disease,” Hartley said.

One of the genes within chromosome 21 regularly produces and releases a protein called amyloid beta, according to Hartley. But because people with Down syndrome have three copies of chromosome 21, they often produce this protein at a higher rate than the general population.

New research study utilizes mouse model to test stem cell treatment for Parkinson’s

Clusters of the amyloid beta protein creates buildup in the brain. This buildup creates issues with communication between neurons and other pathology that is thought to lead to Alzheimer’s, according to Hartley.

“If we know [people with Down syndrome] are nearly all on this trajectory to getting Alzheimer’s disease, we absolutely want to be able to study this so we can eventually be able to identify some interventions to be able to prevent or delay this disease,” Hartley said.

Normally, the brain can clear out these extra proteins, according to Christian. But over time, the brain may not be as effective in doing so, leading to Alzheimer’s disease.

Christian said if people without Down syndrome develop Alzheimer’s, it is generally in their late 70s to 80s, when their brains become more ineffective at clearing amyloid beta.

For people with Down syndrome, however, Christian said the extra release and inability to clear amyloid beta proteins causes them to develop Alzheimer’s as early as their late 40s.

Christian said by the time they reach their 60s, the overwhelming majority of people with Down syndrome will be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Removing plaques of amyloid beta may slow down the progression of Alzheimer’s symptoms.

Christian said many other studies are now exploring this possibility. These treatments are referred to as anti-amyloid therapies.

Because such a large percentage of people with Down syndrome develop Alzheimer’s, researchers can focus on the population of people with Down syndrome with near certainty that they will see onset of the disease, according to Christian.

The ongoing UW study is focused on the Alzheimer’s Biomarkers Consortium in Down Syndrome.

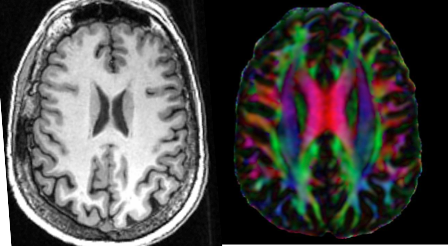

“We’re completing what’s referred to as a natural history study,” Christian said. “That is, following the accumulation of amyloid and then looking at a number of markers. We’re following that over the course of time in what we call a longitudinal study.”

Christian said researchers track how people are performing on cognitive or memory tests and lifestyle components. Tracking these test results alongside looking at the biomarkers allows researchers to see the onset of biological markers in Alzheimer’s in relation to the symptoms.

Christian said rather than searching for a specific treatment, the study is focused on when and how a treatment or intervention may be most effective in this progression of biomarkers and symptoms. If an intervention does not occur at the most effective time, the benefits may not be as clear.

“We’re working closely with another study that is going to be developing treatment trials for people with Alzheimer’s disease,” Christian said. “We feel that all of these findings and results could easily be translated to the general population.”

Christian said once researchers know when amyloid beta plaques become present in the brain and when treatment is most effective, this information can be used for the general populous.

With an aging population in the U.S., Christian said the incidence of Alzheimer’s is going to increase and researchers must work quickly to combat the disease.

“It’s really bringing together many of the valuable resources that we have here on campus as well as expertise across many different fields in this project,” Christian said.