In 1981 the AIDS epidemic officially began in the United States, and the world regarded an HIV diagnosis as a death sentence. Searching for a name for this terrifying new illness, the press began using the term GRID (gay-related immune deficiency). When it was determined that the disease is diagnosed in people of all sexual orientations, the Center for Disease Control introduced acquired immune deficiency syndrome as the correct term. In the wake of technological and medical advancements, testing positive for human immunodeficiency virus no longer means resigning to a painfully immediate death. According to recent studies published in PLOS One, the average person in North America that tests positive for HIV can expect to live to 63 — and gay men live even longer, to an average age of 77.

What is HIV/AIDS?

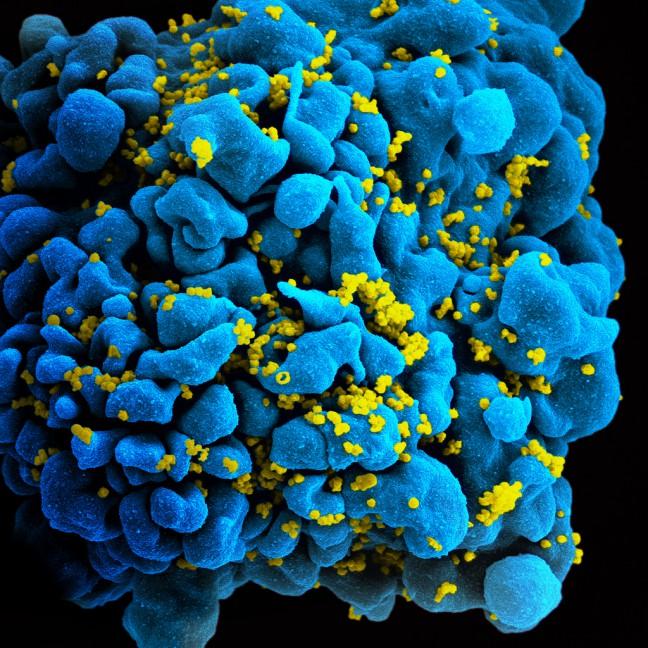

It is impossible to “get AIDS.” It is caused by infection with HIV. HIV enters the body through the bloodstream or mucous membranes (places where blood vessels are close to the skin, making infection transmission possible). These mucous membranes include the lining of the vagina, cervix, or womb; the urethra of a penis or inside the foreskin; and the delicate lining of the anus. Once a person is infected with the virus, HIV attacks the cells of the immune system, rendering the body unable to fight off infection. A person who tests positive for HIV can find the virus in their semen, pre-cum, vaginal fluid, breast milk, blood and rectal secretions.

If HIV infected fluids enter the body, that person is at risk for HIV. These fluids may enter by unprotected vaginal, anal or oral sex, although oral sex carries a very small risk in comparison. Sharing dirty needles, such as those used for intravenous drugs, is another prominent route of HIV transmission. HIV can also be passed along through pregnancy, birth, breastfeeding from mother to baby or via blood transfusions and medical procedures (most countries have processes in place to prevent this, including the United States). It is impossible to contract HIV via surfaces, air, kissing, insect bites, sterile needles or water.

Get Tested!

Health care providers test for HIV by taking blood or oral fluid samples. HIV tests may not detect infection between the first two weeks and three months after exposure, so it is important to get tested regularly, especially if you have multiple sexual partners. A test should be taken if you are pregnant, breastfeeding, not always using condoms or sharing needles. For Badgers who wish to get tested, UHS offers screening and treatment for HIV. Want to get tested elsewhere? The National AIDS Manual offers a tool to search for HIV-related services all over the world. Because HIV symptoms are so similar to symptoms of other illnesses, the only way to know for sure if you have HIV is to get a test.

Testing & Dating Positive

Testing positive for HIV indicates nothing about you except a compromised immune system. It may feel like the end of the world, but you are not alone, and today there are many resources available for treatment. If you struggle with a diagnosis, contacting an HIV counselor or psychologist could be a helpful step. Deal with emotions however you please—scream into pillows, write about it and/or cry for hours. Then get information, inform any past or current partners and seek out treatment.

Often people assume that a positive test result for HIV means the end of their sexual and dating careers. But the reality is that people continue to date after their diagnosis and can do so quite safely, with a very low risk of infecting partners. A serodifferent couple consists of one partner who is HIV-negative and one who is HIV-positive. In these cases, HIV prevention and family planning should be openly discussed as a couple and with a health care professional. Be sure to use condoms and other methods to prevent passing along HIV.

Luckily, antiretroviral drugs can lower the amount of HIV in the body, lowering risk of transmission. Treatment thus acts as prevention. HIV treatment can be taken when you need it to stay healthy as well as before you need it, to protect partners from infection. HIV-negative partners can take pre-exposure prophylaxis to lower risk even further.

There are many communities available to people who have HIV, such as Poz. Dating websites like PozMatch offer opportunities to find other people who are HIV-positive. It is possible to enjoy a full, healthy, sexual and romantic life with HIV/AIDS — mostly in wealthier parts of the world where treatments and prevention measures are available.

The Stigma

Although we have made progress in better treatment of those with HIV/AIDS, those who are positive still face stigmas and discrimination from their families, peers, health care providers and educators. Remember that HIV is not a “gay” disease. People of all sexual orientations, genders and backgrounds can have HIV. The fear and homophobia of the 1980s is long gone. People may also harbor assumptions about HIV-positive people, drug use and prostitution. These stigmas make it difficult to manage and fight HIV.

No one who has HIV should be regarded as less clean than others. Try using “negative” instead of “clean” when discussing STI and HIV status; it helps remove “dirty” associations from HIV-positive people. Push for governmental policies that would protect HIV-positive people from discrimination. Fight for health care that includes effective, affordable treatments. Support equality in employment and advocate for those who are sometimes regarded as promiscuous or dirty because of their HIV status. Testing for HIV is not a test of morality or history and should not be treated as such. Treat all people of all HIV statuses with respect and care.

PEP and PrEP

Post exposure prophylaxis, or PEP, is a form of emergency prevention to be used if someone thinks they have come in contact with HIV. It prevents the virus from establishing itself in the body and can be found at many clinics and health centers, including UHS. PEP is also important for people who have been sexually assaulted. It should be taken as soon as possible after exposure.

PrEP, or pre-exposure prohylaxis, is fairly new to the scene of HIV prevention. It is an FDA-approved pill prescribed by a doctor that helps prevent HIV among HIV-negative adults (especially when used with condoms or other prevention methods). If taken everyday, the risk of getting an HIV infection is much lower — up to 92 percent lower. Although many have reported unfavorable side effects such as nausea, these side effects occur in most HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention measures. Many insurances cover PrEP, but without assistance, the drug can be expensive — just as with other HIV/AIDS medications.

In honor of World AIDS Day, take a moment to think about all the people who lost their lives to HIV/AIDS. Use condoms, get tested regularly, educate others and celebrate the amazing advancements the world has made in preventing and curing HIV/AIDS.

Questions? Want to find out more? Attend Sex Out Loud’s No Stupid Questions event Dec. 3 at 7 p.m. in Memorial Union to speak with experts about HIV/AIDS.