Artist Zora Murff, an Iowa-based photographer, has an interest in visually documenting the criminal justice system and its effects on minorities and children.

Murff used to be a tracker for juveniles in trouble with the law, meaning he served as a middleman between the minors and the police to prevent future run-ins with the law. The things he saw while working in this position inspired him to take pictures so the public could see what his job entailed.

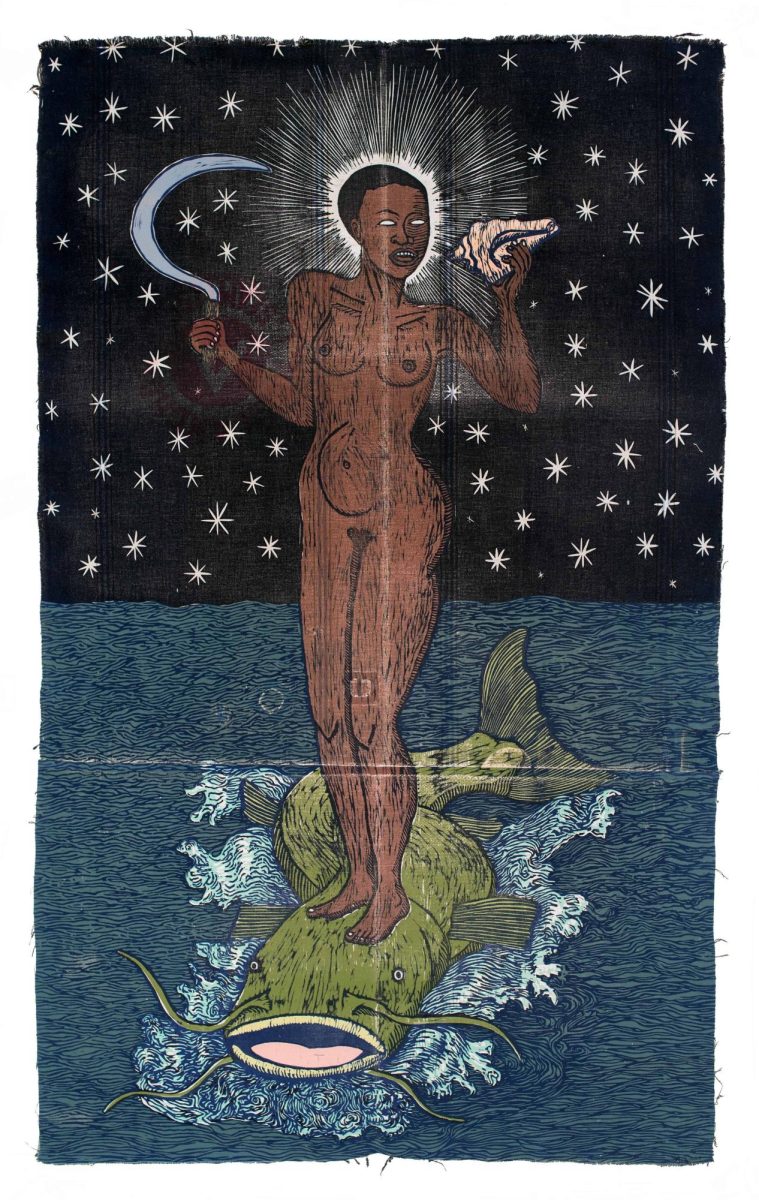

Murff’s newest exhibit, “Corrections,” features a gallery of photos of the youth he used to work with who have been in and out of the system at a young age. The gallery will be open at the Class of 1925 Gallery at Memorial Union until April 24.

The Badger Herald talked with Murff about his entry into photography, his experience as a tracker and the ways factors such as socioeconomic status, education and race affect minors’ experience in the criminal justice system.

The following interview was edited for style and clarity.

The Badger Herald: When you first started as an undergrad, did you know what career you wanted to pursue?

Zora Murff: No I didn’t. I started with my undergraduate degree in psychology and I thought I was going to be a counselor or psychologist, but once I got though the track I just realized that wasn’t what I wanted to do. I graduated, got my degree and worked a few years in the human services field with people with disabilities and adults with mental illnesses. Then I ended up moving to Iowa City, where I got a job as a tracker because I was looking for something related to my degree.

While I was working in that field for a few years I was trying to decide what it was that I wanted to do because I knew that wasn’t going to be my long-term career. I bought a camera and starting taking pictures as a hobby. People were constantly telling me I was pretty good at it so I decided to go back to school for art.

BH: What made you take your photography to the MFA level?

ZM: I was always inspired by my photography professors. After a while I got to thinking that this was definitely something I could do as a career. I really fell in love with making art and I’ve always seen myself as an educator in that capacity. The two went hand in hand and once I finished up with my degree track at the University of Iowa I decided to enroll in grad school and get my MFA.

BH: You mentioned that you were a “tracker.” Could you describe what that job was like?

ZM: Tracking was part of what’s called a community-based service. Rather than having kids stay in long-term incarceration, they can be released from the detention facility and be put on probation. The community-based services provide continual contact to the kids. When they’re on probation they have certain goals to be able to fulfill their probation requirements ― that’s where the trackers come in. I followed up with them on a consistent basis depending on their need level. We would take them to community service if they had hours to fulfill. I would do follow-ups at school if a part of their probation was to ensure they were attending school on a consistent basis. I would also give their grades to their probation officer or do drug testing. The community-based services are meant to decrease any continual contact with law enforcement. In a lot of situations where kids are on probation, they might get into trouble or fight with their parents, which might make the police get involved again and lead to additional charges or more time in the system. Rather than calling the police, I would show up to try and de-escalate the situation so they have less contact with the criminal justice system.

BH: Was there a particular person or story that inspired you to start documenting this?

ZM: No, not necessarily. Once I got to an advanced photography course we were required, for the semester, to make one cohesive body of work. I was working full time and going to school full time so I had to find a way to balance the two. When I got the job I had always thought this would be interesting thing to take photos of ― a kid’s journey through the system. So I used that course to take advantage of that opportunity and that project kind of continued to grow.

BH: Most of your images don’t include faces. Is this an artistic choice or out of respect for those being photographed?

ZM: It was a limitation because when kids are in the system they have what’s called ‘protective status,’ which means their identities are never released to the public unless they commit a felony. When I went to my supervisor asking her if I could work on this project, she gave me permission but that was a requirement ― that I couldn’t reveal any of their identities. Even though it started as a restriction, it really became an integral part of the project itself. The idea of anonymity inside the system and not being able to identify the kids.

BH: Do you have any personal connections to the people in the photographs?

ZM: They’re all kids I provided services to as a tracker. Over time, when working with them, I had to develop relationships and be an effective positive force in their life. But professionally you’re trained to have a sort of distance with them because you’re essentially a consequence. I always had a positive relationship with the kids, but once I started working on the project, I noticed that our bonds started to strengthen even more. I opened up to the kids about my own life and things I was interested in and really created more of a solid bond.

BH: Do you think this was beneficial to your job at the time? In what type of ways?

ZM: Most definitely. As a tracker you’re always walking into difficult situations and you have to be able to think on your toes. When they have a strong connection with you, they’re more likely to slow themselves down and rationalize through situations rather than decide they’re not going to speak with you, or do what they want, or put themself in a situation where they might get into more trouble.

Student art showcases social justice, human rights issues prevalent in society

BH: What do you want people to take away from your exhibit or your images by themselves?

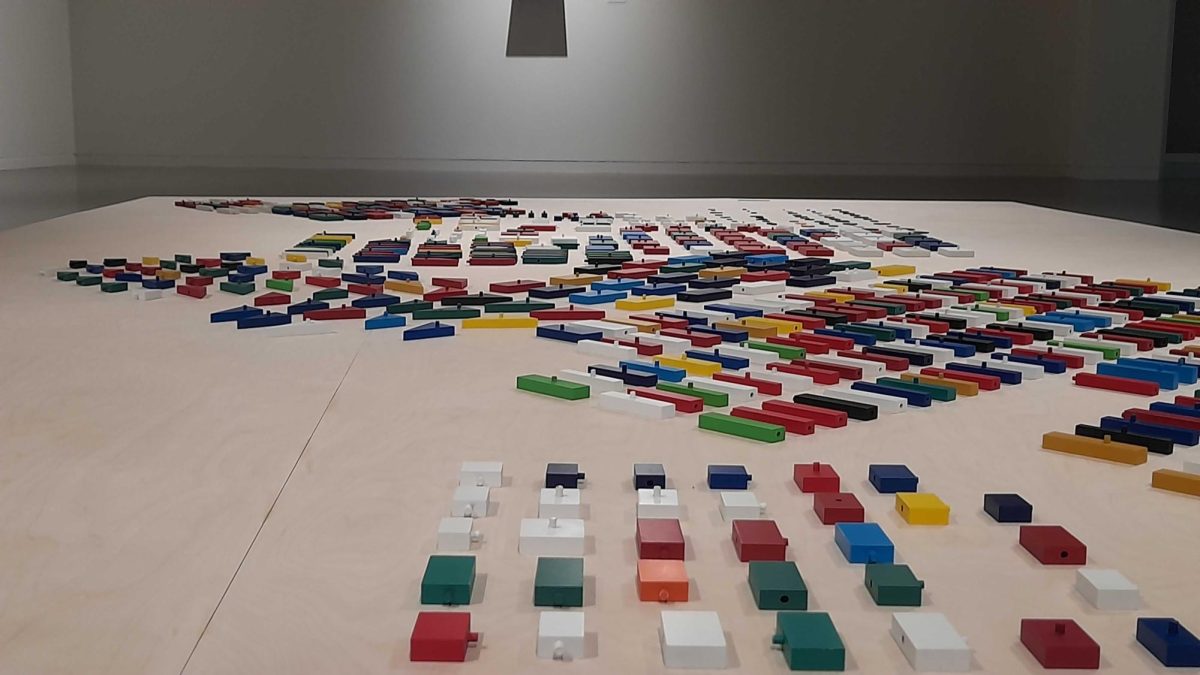

ZM: For me it was about providing this window into this system and process that isn’t something a lot of people know about unless they have contact someway. There’s a lot of privacy built into it, especially with the electronic monitoring and drug testing. Once someone gets pushed into the system, it becomes someone else’s problem and it’s not the public’s anymore. I think these images can inform on some level and hopefully inspire people to learn more about these things. Really, it’s up to them to figure out what the structure of the criminal justice system means to them. If they want to enact change, they can bring themselves to those realizations by looking at those photos. Part of it is also decreasing the stigma.

BH: What made you decide to have an exhibit in Madison?

ZM: I was talking with a professor and they told me about a call for entry at the university. I try to continually get work in different places to connect with a wider audience.

BH: I know the answer might be obvious, but are there any changes in the criminal justice system that you would like to see?

ZM: Yeah, I think there are a lot of things that can be changed about our practices not only in the juvenile criminal justice system, but the criminal justice system as a whole. A lot of the kids I worked with lived in conditions of poverty. There’s a higher number of kids who live in poverty so the system tends to impact them more. Matters of race and the disproportionate minority contact especially, it’s a really terrible situation. It’s up to us to evaluate these disparities that happen across racial and economic lives and figure out how we can fix those problems.