On Madison’s east side, in a neighborhood far removed from the clamor of downtown and the university stands a little white house, undistinguished among those surrounding it — till the backyard is taken into account.

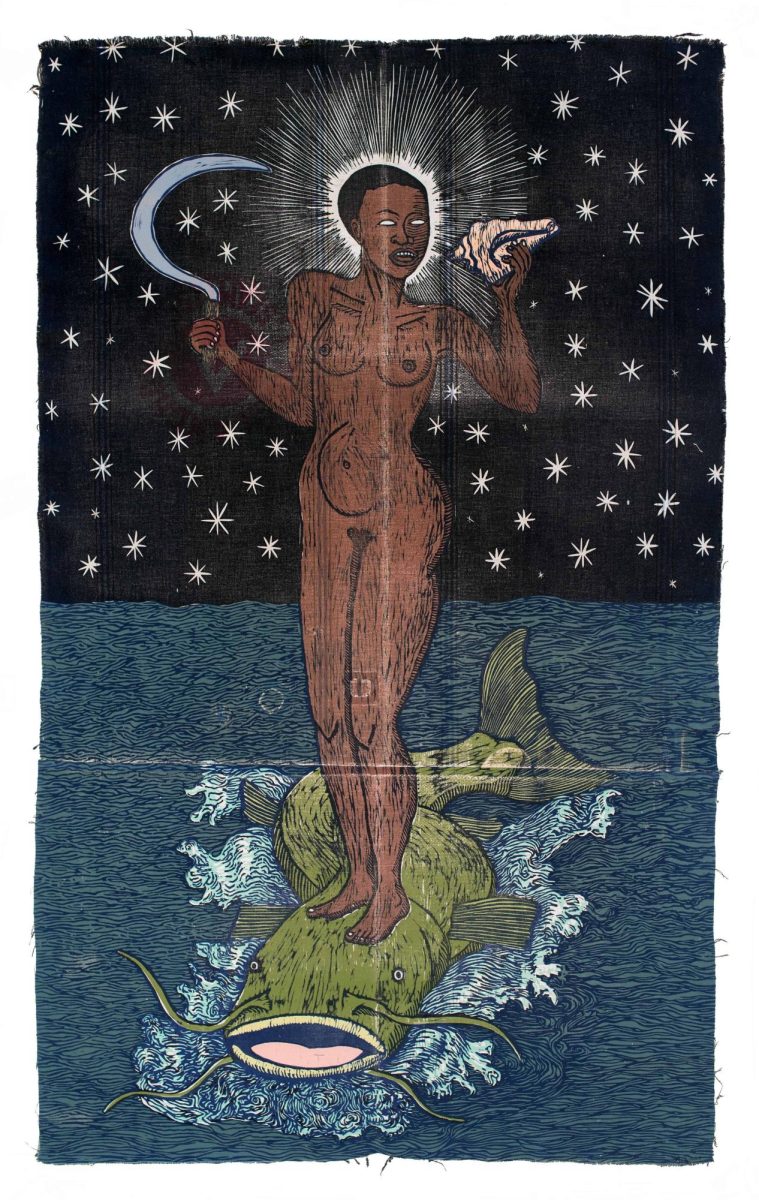

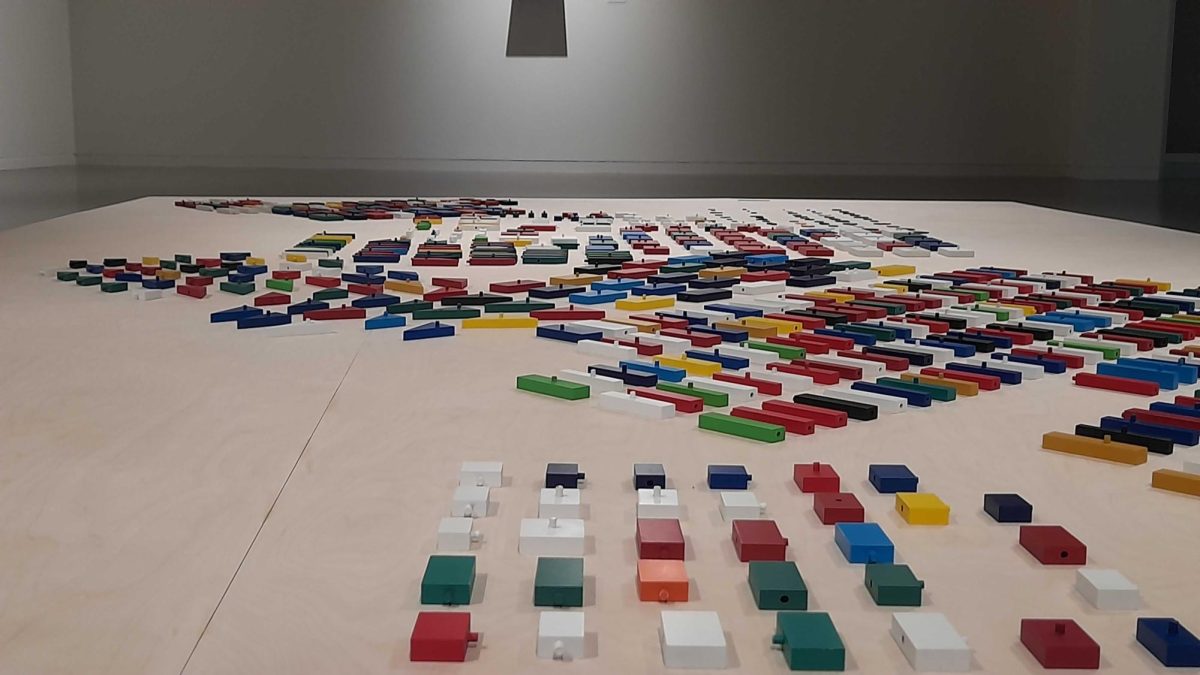

Little known to some, the property is a local landmark: the former home of late folk art legend Sidney Boyum, who died in 1991. Behind this industrial photographer and homegrown sculptor’s former residence, dozens of the artist’s abandoned sculptures eerily rest in the backyard, decaying under the shade of a few trees. Inside the home, countless works of his art await their fate.

Dane County recently acquired the property after it collected more than $18,000 in unpaid property taxes. Originally, the plan was to auction the property off in mid-September, but after a group of neighborhood art enthusiasts’ efforts, the country agreed to hold off the auction until next October. This gives the group more time to discuss options for saving his art.

“We were trying to make sure the property didn’t get sold to someone who was going to bulldoze the place and pay no attention to the artwork there,” said Brian Standing, Dane County senior planner and leader of the community effort. “It was a huge achievement to get that far.”

Currently, the group can’t permanently remove any sculptures or artwork from the property without Dane County’s permission. Due to poor conditions inside the home, Standing said the county will allow them to temporarily store the home’s artwork offsite.

In total, Boyum’s property contains 20 sculptures — the majority strewn about the backyard and one, a Buddha, built into the wall of the living room. The house’s interior also contains a sizable collection of Boyum’s flat artwork.

For many, Boyum’s artwork holds a special place in not only Madison’s, but the east side’s story. His artwork, which he began working on after his retirement as an industrial photographer, is sexual and unorthodox. It describes not only his own complicated and volatile personality, but the alternative neighborhood in which his artwork is situated.

“The collectables in his home are awesome and quirky,” Karin Wolf, Madison arts program administrator said. “People value him for what he expresses, which is an everyday person’s right to creative expression, and an insistence upon it. [He] marks a certain spirit of Madison.”

Many familiar with Boyum’s work appreciate its do-it-yourself nature; Boyum taught himself how to sculpt. Still, few realize the darker side his personality represented.

“Sid had a lot of anger; he had a dark side,” said Carl Landsness, once a teenager who lived next door to Boyum. “Some people considered his artwork pretty crude, and many considered him personally pretty crude and vulgar.”

Landsness said Boyum’s anger often came out around his family — he said he often could hear Boyum screaming at his mother. Unhealed wounds and deep family dysfunction are possibly part of the reason Sid’s heirs chose to never occupy the house after their father’s death, Landsness said.

“Sid’s art is part of that,” Landsness said. “Much of it was his way of expressing that pain and anger.”

Boyum had a light side as well. Landsness said Boyum loved to tell creative tall tales, and could often be found chatting with neighbors, fishing or wandering about with a big cigar in his mouth.

To preserve Boyum’s legacy, many challenges remain. Organizers already plan to begin sorting out the bigger remaining questions at a meeting Tuesday at the Goodman Community Center.

One of their first goals is to seek a county ordinance amendment so the city could eventually purchase the property for less than its $50,000 appraised value, then transferring it to a non-profit.

Various historical and art museums could eventually house the refurbished artwork, and organizers also want to explore acquiring rights to duplicate sculptures that may be too damaged to salvage.

But while saving the art is a given, not all organizers agree how it should be preserved. Landsness said he represents some in the group who wish to keep the artwork and sculptures on the property, alongside Boyum’s personal items.

“Part of his expression is in the house itself, in the way he created, and in the way he integrated his life emotions into the physical structure in which he lived,” Landsness said.

While some estimates to refurbish the property are upward of $1 million, Landsness said this might not be necessary.

“Some of the places that do not conform to building codes and regulations and health standards are the most uplifting places to live, even though they break all kinds of rules,” he said.