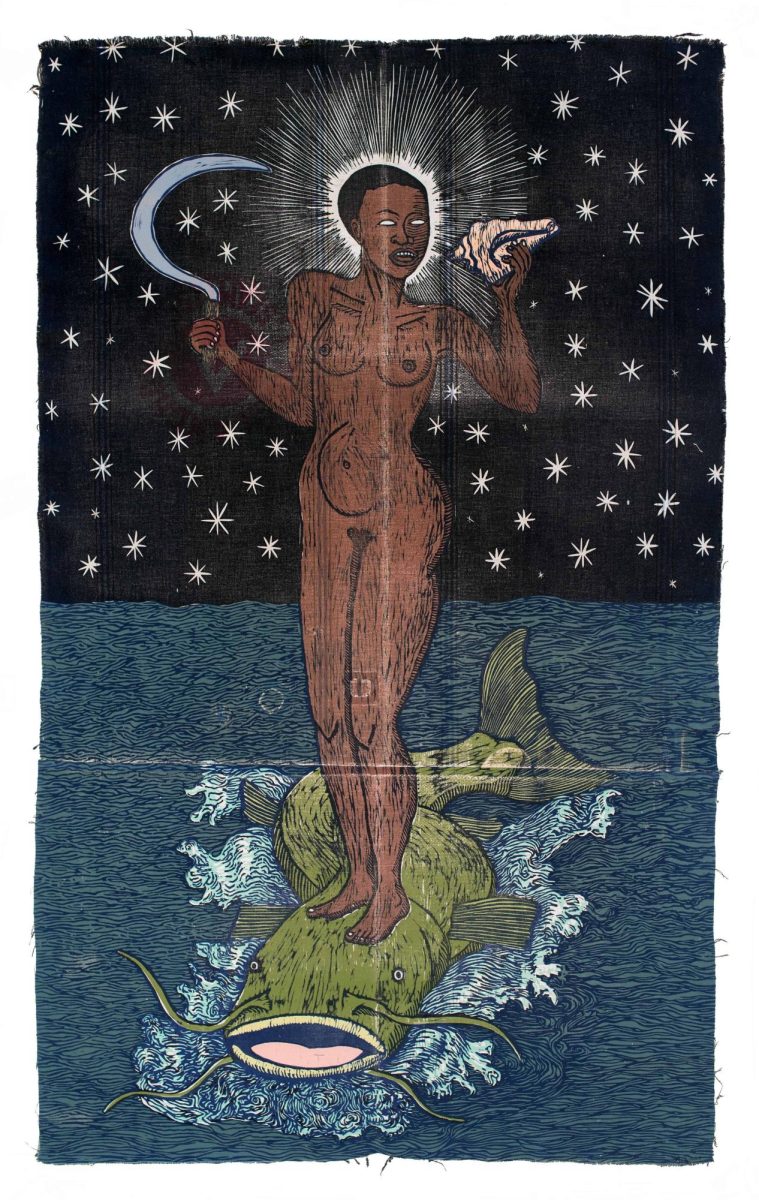

At first glance, Zofia Stepień’s sketch, “A Portrait of a Camp Friend — Wanda,” seems to depict a woman in the prime of her life. Her hair is long, flowing and healthy. She is fully dressed in everyday clothing, and her cheeks are full and round.

But there is a subtle hint of ambiguity in her caricature- her wide eyes, the way her full lips part in longing. This feeling, this air of unhappiness, is a reminder of the painting’s origin: the Auschwitz II-Birkenau concentration camp, where Wanda was likely another female prisoner.

Stepień created some of the only portraits of female prisoners that survived the second world war.

The SS officers at the camp would have given Wanda a number to replace her name, a dirty uniform to replace her nice clothes, replaced her flowing locks with a shaved head and made every attempt to strip her of her humanity.

A photograph of this portrait is one 20 pieces on display at Memorial Union through Oct. 5 as part of the “Forbidden Art” exhibit. The collection that captures the sketches, paintings, greeting cards, fairytales and sculptures of the Holocaust is indicative of how prisoners used art, both realistic and fantastic, to fight for their humanity. They are all made by prisoners of Nazi concentration camps.

The concept of “Forbidden Art” came from the fact that making art was strictly prohibited at the camps. These artists risked immediate execution to create small manifestations of their undying human spirit. Pieces in the exhibit were drawn on the likes of cigarette scrolls and etched into links of a bracelet. One book of sketches that attempted to document the true horrors of camp life was bound with a large chunk of human skin. They were hidden between the bricks of their barracks and in bottles buried far beneath the earth as secret testimonies to what professor of Jewish studies at the University of Wisconsin, Rachel Brenner, described as “the invincible human spirit.”

Most of the original pieces are very small and fragile; all of the artwork is housed at the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in Poland. But the amplified photographic images, displayed at UW, have been touring all over the world, and will end up at the United Nations for the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz II-Birkenau.

Auschwitz II-Birkenau concentration camp became a major site for the Nazi “Final Solution” — complete extermination of the Jewish peoples of Europe — but it began as an internment camp for Polish political prisoners.

“It has become such an emblem of the Holocaust, which was for Jews,” Brenner said. “So people don’t know it was a horrible camp before for the intelligencia of Poland. The Germans wanted to eliminate the Polish elite, the educated, doctors, lawyers, artists, professors.”

J.J. Przewozniak, curator of collections for the Orchard Lake Polish Mission and project manager for “Forbidden Art,” has been traveling with the collection throughout North America as part of the Polish Mission’s goal to promote modern Polish culture.

He brought it to Madison after a member of the Polish Heritage Club of Wisconsin-Madison reached out to him as the first cultural organization to take on the exhibit. Marjorie Morgan, member of the Polish Heritage Club, has been referring to the club’s match with the Porter Butt’s Gallery in Memorial Union as providential.

“The gallery there was scheduled for a remodel, but that remodel was delayed and that is the only way we were able to get it there,” Morgan said. “It is really meaningful to the college and its community.”

Most pieces represent one side of the spectrum between the horribly realistic depictions of life at the camps and the shockingly idealistic imagery of life before the war. Stepień hoped her sketch of Wanda would fall solely in the latter group.

“I’ve seen their huge, famished, black eyes and their emaciated bodies…almost all women had ulceration, furuncles, suppurating wounds… I just tried to embellish it all,” Stepień said of her painting, as quoted in the exhibit.

The juxtaposition between the real and the fantastical is a powerful statement about the motivations of the prisoners. Diagonally across the room from Stepień’s “Wanda,” there is a portraiture of a man. He is clearly frail with wrinkled skin and deep-set eyes. His expression exudes fear and contempt. It is part of a collection of 114 sketches by Franciszek Jaźleckl depicting his fellow prisoners of different nationalities and ages. His first few sketches were discovered by the SS and destroyed. After three months in the penal company, a contained area for those in the camp who had disobeyed rules of some kind, he started his collection from scratch.

Where some might have created this realistic art for documentary purposes, an unknown sculptor at Auschwitz II- Birkenau created a sarcophagus in memoriam of a fallen prisoner. Inside the merely 12-centimeter-long sarcophagus, there was a partially-burnt human bone and an inscription of birth and death dates, identifying the victim at age 25.

On the other end of the spectrum, a series of greeting cards and fairytales stand in sharp contrast to the honest and colorless works. One item was a page from a fairytale book made for the author’s son who was left at home. The book was an allegory for life in the camp. By appearance alone, “A Fairytale about the Adventures of a Black Chicken,” looks like the haphazard musings of skilled artist. In reality, it was a way for a prisoner to communicate camp to a lost child.

A collection of greeting cards by male prisoners entitled, “An Album for Women-Prisoners of the Budy Subcamp,” was filled with personal greetings and home addresses given at Christmas time. It is filled with idealized landscapes of how life used to be for the prisoners. It could have provided a brief escape or served as a reminder of the irretrievable past, but like the rest, it was an act of sabotage against the Nazi plan to rob them of their humanity.

“Through the expression of the artists, we can see the most determined survival efforts that humanity has ever known, and even in the finest detail of some of the pieces, they can reveal to us the most intimate aspects of camp life,” Przewozniak said.

In a speech she gave regarding the exhibit, Brenner said that we can never answer the question of why these prisoners risked so much to produce this art, because no one in the audience had come close to experiencing the horror of Nazi concentration camp life.

Przewozniak expounded on that idea. He believes a concrete answer can’t be given, but the message of Auschwitz is realized when the question is posed.

“When we remember that they [evils of the Holocaust] did occur, and when we force ourselves to think about these difficult open-ended questions, we do the most for their memory,” Przewozniak said. “We do the most proactive thing to stop it from happening in the future.”