The latest exhibit to open at the Chazen Museum of Art, “The Golden Age of British Watercolors, 1790-1910,” gives visitors and art aficionados a closer look at one of the defining eras in Victorian art history.

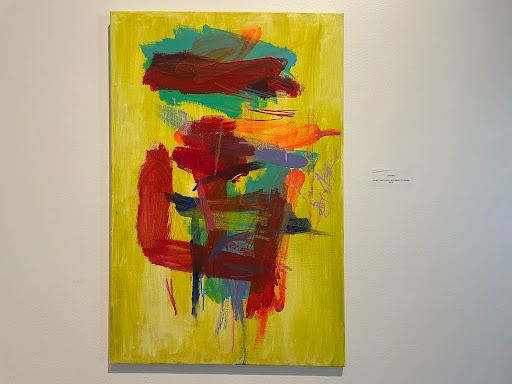

The Chazen’s Garfield Gallery prominently displays watercolors of varying hues and sizes. Familiar pieces from masters of the medium such as John White Abbott, Isaac Cruikshank, Francis Danby and Samuel Palmer are dispersed equally among dozens of paintings from other lesser-known yet equally talented artists. In all, about 25 works fill the space and visitors are surrounded by works from the Chazen’s permanent collection, as well as pieces loaned from the Yale Center for British Art.

Many paintings have taken up residence at the Chazen for the exhibit, and all have merits. However, for the uninitiated, Alfred William Hunt’s visualization of The Devil’s Bridge in Switzerland is especially striking, depicting a precarious stone bridge atop a roaring mountain river. Another stand-out is Joseph Noel Paton’s pastoral landscape, injecting life into a lush, wooded forest through which meanders an ebbing winter stream. The ethereal, dreamy quality of watercolor breathes vibrance into landscapes and portraits alike.

There are a variety of watercolors on display, from the small still-life paintings of the stereotypical bowl of fruit to giant works of art that depict colorful, detailed landscapes. Watercolor is a portable medium – meaning it is very adaptable to new settings – and the exhibit pays tribute to that fact by going beyond the traditional definition of artistry and displaying such things as travel souvenirs and commercial illustrations.

The exhibit in the Garfield Gallery doesn’t only seek to present beautiful artwork; it’s also dedicated to unraveling watercolor art for the average tourist. A sizable area of floor space is used to give a quick, truncated Watercolor 101 lesson for the interested amateur and the returning artist alike.

Particularly interesting are a series of paintings laid out in a corner of the gallery, which depict a green pear on a flat, white table. Each painting is drawn according to a different style – from the simple “solid wash” that paints flat and defined colors, to the “gradient wash,” which allows the colors to fade a little more. The exhibit familiarizes the viewer to the processes and techniques the masters used to create some of the stunning paintings on display.

Even the single non-watercolor painting in the gallery (Scottish Lovers, Daniel Maclise, oil on canvas, 1865) is used to teach the visitor about the historical perspective on watercolors. For example, the museum guide describes the artwork as an allegorical device for the femininity of watercolors; the painter believed oil paintings were superior to watercolors, and that naturally shows up in his work, the exhibit explains.

For those of us interested in learning more about this fascinating medium, one could do a lot worse than the Chazen exhibit, which provides both excellent examples of watercolors and detailed information about how they were drawn, and why they continue to fascinate – even hundreds of years after the artist first laid brush to canvas.

The new exhibit runs through Dec. 2 and can be found at the Leslie and Johanna Garfield Gallery on the second floor of the new East Wing. Although donations are requested, the Chazen Museum of Art is free to enter.