The Madison Museum of Contemporary Art began its exhibit on the Chicago Imagists Sept. 11 with a talk by several members of the movement. That night, Gladys Nilsson and Art Green sat down with a MMoCA representative in an attempt to draw out memories of the time that inspired these distinctive works of art with other Imagist artists in their circle of friends chiming in to tell their stories in front of art patrons and the Madison public alike.

Green, an Imagism artist who has probably heard the joke about “Art does art” more times than he cares to remember, talked about how he had tried to adapt his interests into something like design or architecture that would translate into a fiscally suitable career, before finally realizing that art was his true passion.

The MMoCA took a creative approach in how it laid out the exhibit by splitting the artwork into two floors – Chicago Imagists at the MMoCA and Chicago School: Imagists in Context. The latter exhibit includes work inspired by Imagism, as well as by those who inspired the Chicago Imagists.

Gladys Nilsson also had much to say about the era that, unbeknownst to them, would one day be termed the Chicago Imagist movement. She and the other pals would get together and “make art,” an experience that would one day have its own name and be studied as a defined style.

Their shows at the Hyde Park Art Center – usually followed by parties with a signature punch made of vodka, lime juice and a few other choice ingredients – included shows with titles like “Hairy Who,” “Nonplussed Some,” “False Image,” “Marriage Chicago Style” and “Chicago Antiqua.” Their art was by no means monotonous; in fact, it was very different. Their close friendships and interests in art allowed them to easily share ideas and inspiration, something which undoubtedly allowed for the success of the Imagist movement.

Nilsson’s watercolor portraits stood out among the high levels of acrylic and other mediums in the gallery – such as Ed Flood’s Aluminum Floater, which you could walk right into. Her work flourished beside the other styles. She said she didn’t realize there was gender inequality in the art field until she went to New York City and other big cities, because her work and that of other women at the Hyde Park Art Center had been so accepted.

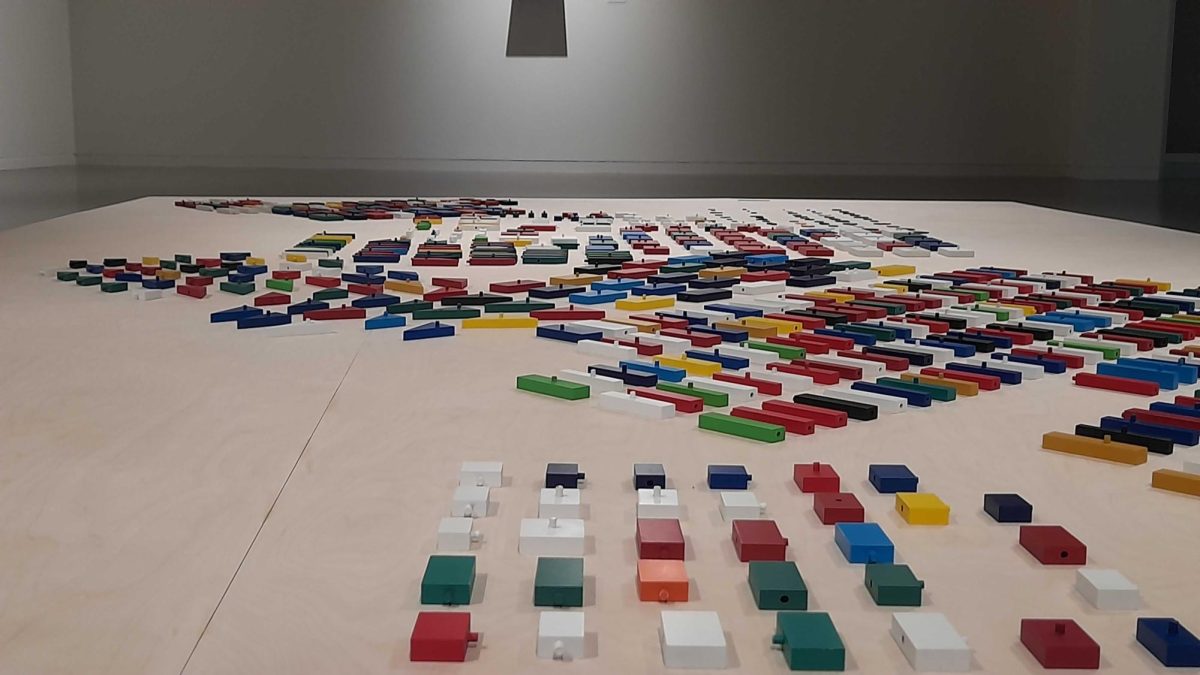

All of the artists benefited from teachers like Ray Yoshida, who taught at the school of the Art Institute of Chicago (1959-2005). He also had his own work in the exhibit, which consisted of shapes cut out from comic books and placed strategically on matting. These employed good spacing, and he chose images with complimentary, neutral colors.

Jim Nutt’s abstract portraits capture common themes, by showing how art can reveal a person’s emotions and attitudes in ways that realism cannot. The distortion represents a personal as well as national angst. Nutt was experimental with shapes, letting the individual’s imagination declare the meaning, such as the alien-like figures in “Don’t Make a Scene.”

Christina Ramborg’s darker toned acrylics from 1980 are distinct from the rest of the exhibit in that they demonstrate a more sophisticated style. Her cluster of works shows the progression from teenagers to adults through her skill and artistic decisions.

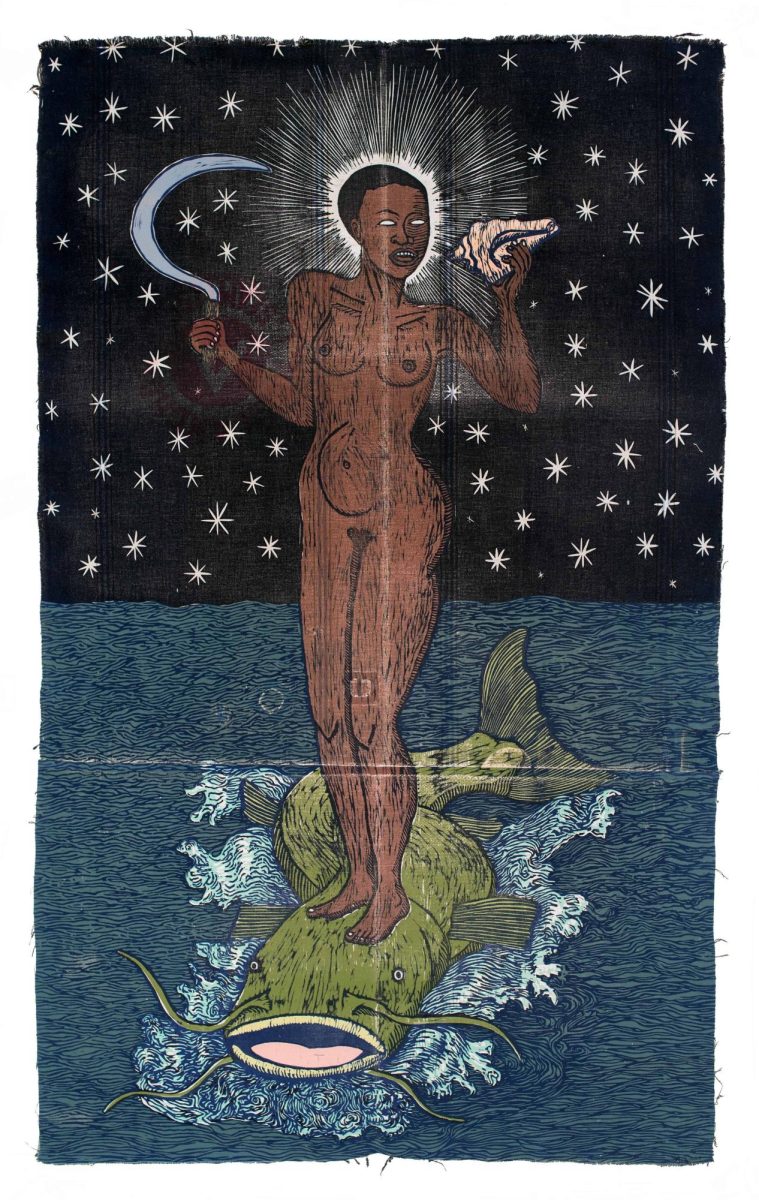

The transformation in age was more visible in Karl Wirsum, who was literally tangible in the second row of public seating at the pre-opening gallery talk. He sat calmly and modestly in an orange baseball hat, a whisper of the once-youthful artist his friends described. It became incredibly hard to imagine that he had once crafted the hugely ornate, cartoonish graphics hanging in the gallery upstairs. His works are grotesque and distorted, and show the hairy, oozy, ugly, tattooed parts of people – not typically valued as subjects for works of art.

The artists that brought Chicago the iconic “Hairy Who” have also given a rare treat to Madison – a glimpse into the human sources of this great art.

The two galleries on Chicago Imagism will be at the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art on State Street until Jan. 15.