“Incredibly hot liquid, molten, soupy stuff” is more likely to evoke images of volcanic eruptions or other geologically destructive forces than the colorful, delicate artwork that Audrey Handler is actually describing here. She and the other members of The Women of Madison Glass work with such fiery-hot material regularly, eventually cooling and crafting it to create glass artwork so fragile in appearance that one cannot help but feel it is best to admire only at a distance.

The Women of Madison Glass came together at the University of Wisconsin Glass Lab. Despite their varied backgrounds and considerable range in age, the group — composed of Pamela Cremer, Audrey Handler, Shayna Leib, Lisa Koch, Renee Miller-Knight, Quincy Neri and Harue Shimomoto — all met either directly or indirectly through the UW Glass Lab.

In an interview with The Badger Herald, Handler, Koch and Shimomoto spoke casually about their group and experiences as glass artists. Since their days at UW — or in the case of Shimomoto, in her ongoing stay at the university as a graduate student — the seven women have continued to take an interest in glasswork and recently collaborated to create The Women of Madison Glass as a way to combine their artwork into a group exhibition at the Overture Center, currently on display in Gallery I.

“When I started, it was the beginning of the glass program,” said Handler, a friendly, middle-aged woman one would expect to see melting toffee rather than silica at four-digit temperatures. “There was no other glass program in the country.”

The styles of the glassworks vary considerably between artists, and range from Neri’s blown glass of carnivorous-looking plants, which could be described as somewhere between monstrous and cartoony, to Shimomoto’s fused glass and Pyrex tube creations so massive and delicate that the mere thought of transporting such a piece is mindboggling.

“That’s difficult,” said Handler with a laugh when questioned about moving glasswork from the studio to a gallery. Koch adds, “It’s specific for each piece, but usually involves lots of bubble wrap.”

But such difficulties are an old hat for these patient artists, who typically have to wait more than 24 hours after igniting their kilns before they can even begin working with the melting glass inside, which sometimes amounts to more than 50 pounds of scorching, viscous goo. Asking what exactly is put into those ovens to get glass out of them prompted much debate about which types of ingredients with perplexing, longwinded chemical names work best, and which each prefers. Koch, who recently finished biochemistry research at UW, then began speaking about glass’s coefficient of expansion, and it became quite clear that glassmaking isn’t something any ordinary artist can tackle.

“It’s difficult to answer that question,” said Handler. “There’s thousands of formulas to make glass, and it depends what you’re doing.”

But even if the women go about making their colorful creations in different ways, they’re all in agreement over their passion for doing it. Koch says it is glass’ unique properties that make it so appealing to work with for her art.

“Glass can contain a space that other things can’t, and it works with light so well,” said Koch. “Working with hot glass is something different than you’re going to find with anything else. It can be very seductive, very addicting.”

Koch’s fascination with these properties is quite apparent in her works. Her “Infinite Molecular Reunion,” made of glass, steel and wood, is a standing piece that beckons the viewer to look down into it from the top, revealing a seemingly endless display of silver shapes and reflections. Her other works, too, incorporate this interest in molecular structure.

“I’m also a scientist, and I think that shows in my work,” said Koch, many of whose pieces were inspired by the interrelatedness of molecules and particles, which fascinate her because they are recycled infinitely. “Something that’s a part of you was a part of something else before it was incorporated into you,” she added.

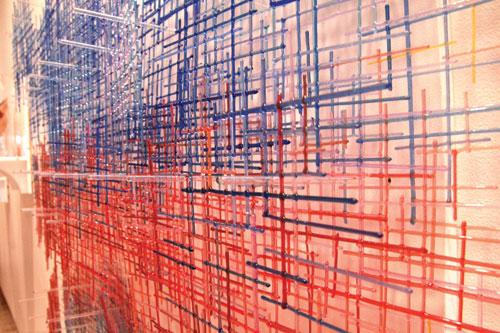

Areas of interests outside of glass also inspired Shimomoto’s fragile art. Her impressively sized “Hazama ni Arumono” is a patchwork of thin glass tubes overlaid in grids with gradients of color pervading the entire piece.

“With that piece, I wanted to have a certain space,” said the soft-spoken Shimomoto, who was inspired by an architecture class, which prompted her to consider spacing as a basis for her glasswork. “If [the glass tubes] are close together, it is one thing, but if they are too far, it is two things,” she said while demonstrating by moving my pen and notebook around the table and spacing them apart differently.

As for Handler, she’s made glasswork her career — as have Leib and Miller-Knight — operating out of a small studio just outside Madison and frequently partaking in organized art tours, though she adds that her furnace is turned off when people visit. It’s just “too dangerous to demonstrate for people,” she explained. Her studio, which she began in 1970, is probably the oldest studio of its kind.

“I’ve been working [with glass] for almost 40 years and I’m still excited every time I get to the studio and dip into that hot glass,” adds Handler.

Handler’s work usually results in colorful, almost whimsical creations. She also has a penchant for focusing on pears. Her blown glass fruits have fitting titles to accompany them: “Summer Pairs,” “Wedding Pair” or “Winter Pairs.” Her pieces also tend to include tiny figurines of a romantic couple (made of something other than glass, but just what she refused to reveal), whose disproportionate scale she uses to make her works appear monumental and almost surrealistic, she says.

Whether pondering Handler’s glass pears or Miller-Knight’s “Japanese Maples,” a piece which seems to embody the simplistic beauty of haiku with its traditional-looking, print-like beauty, no one can question the extreme care that goes into creating such delicate art.

From molten glass to beautifully intricate crafts, The Women of Madison Glass seem to have mastered an art that goes beyond the traditional paintbrush and canvas, shedding light on (and through) artwork that, though relatively new, is here to stay.

“We have spawned an industry,” says Handler. “Glass artists have spawned an industry that has exploded.”

The Women of Madison Glass exhibit is on display through June 11 in Gallery I on the first floor of the Overture Center. The galleries are free and open to the public.