Advertisements are the embodiment of Americana. Whether they’re on billboards on the side of the road, in annoying television jingles or on the back of a newspaper, advertisements of products and services are an everyday part of life — so much so that we often don’t recognize how severely we are bombarded with them. That is, until election season. It seems everywhere one looks, a campaign ad is slapped in the face of every American who consumes any type of media.

But with any type of information, it’s important to analyze the source to find out if they’re credible. This is easy to do with political advertisements on television or radio — the Federal Election Commision mandates a disclaimer must be played informing the audience on who paid for the ad, and that person or group must disclose to the FEC where they got that funding. But for advertisements on the internet, it’s not nearly as simple.

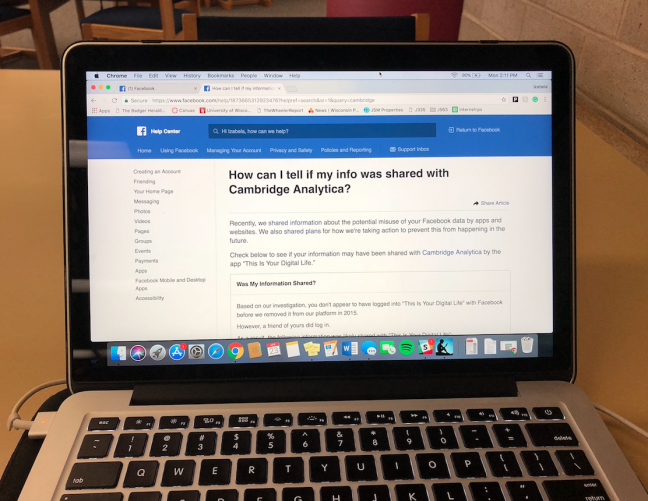

When Facebook was launched in 2004, no one had any idea of its social implications, let alone how it would shift the political landscape. Lately, media attention has been on the Cambridge Analytica scandal, which involved the group amassing the personal data of 87 million Facebook users to tailor political ads and influence election results.

Despite the mass coverage, the actions of political campaign groups on Facebook during the 2016 election are grossly unknown. That’s where Young Mie Kim, professor of the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Wisconsin comes in. Kim’s most recent research project delves into these waters, determining the groups responsible for purchasing political ads on Facebook and those who were targeted by these groups.

Over the course of six weeks in 2016, Kim tracked 228 groups that purchased Facebook ads about controversial political issues. The researchers could not find any trace, online or in federal records, of 50 percent of these groups. Of those 124 “suspicious” advertisers, one in six of them is associated with the Internet Research Agency, a Russian propaganda group that manipulated digital platforms to influence the American electorate. Although they bought a significant amount of political advertisements ranging from abortion to candidate scandals, they are obviously not registered with the FEC, given that they’re an international entity. It would make sense that an organization that isn’t affiliated with the FEC would not be allowed to purchase and place political advertisements online, as that’s the protocol for television and radio. But there are no campaign finance laws that pertain to paid advertisements on social media, so the Internet Research Agency’s activity is legal.

Organizations not affiliated with the FEC were more likely to target “battleground” states with advertisements on divisive issues. According to Kim’s study, Wisconsin is one of the most targeted states, with ads on issues ranging from terrorism to candidate scandals. Similarly, low-income white households were specifically targeted with advertisements focusing on immigration and racial conflict, which only further fueled America’s divisive political culture.

What’s most frightening about Kim’s findings is there are loopholes and relaxed or nonexistent regulation that easily allow for situations like this to happen. The nature of digital advertising makes it difficult to track this type of ad. Digital ads are generally tailored to the individual, meaning they are hidden from the public unless they are consumed in real-time by a particular user. This oversight makes it very hard for them to be tracked and regulated. Furthermore, by collecting and analyzing user data ad groups identify and target specific individuals and customize their messages. The popular media platforms these ads are placed on, like Facebook, are exempt from the FEC’s disclaimer requirements because they are considered “too small” to include any information on the source of the ad or who’s paying for it.

The troubling thing about this entire situation is not the immorality of it all — it’s the fact that there are currently no laws that sufficiently address political advertising. The acts of Facebook and the Internet Research Agency were grossly unethical, but not entirely illegal. Although Facebook’s recent promise to begin requiring disclaimers on political ads is promising, more needs to be done by the government to make sure elections stay fair and ethical. Given America’s overly relaxed campaign finance laws, the actions of the Internet Research Agency and other, smaller dark money groups were inevitable. Humans adapt to the ever-changing technological landscape as quickly as new updates are available — it’s time the government does the same.

Abigail Steinberg (asteinberg@badgerherald.com) is a freshman majoring in political science and intending to major in journalism.