Despite the fact that 1 in 55 Americans are currently on parole or probation, community supervision remains one of the least researched and least effective aspects of the American criminal justice system.

Created as an alternative to incarceration, community supervision has actually become a pipeline directly into prison. In 2016, nearly 350,000 people were sent to prison, not for committing a crime, but for violating one of the many complex, convoluted terms of their parole.

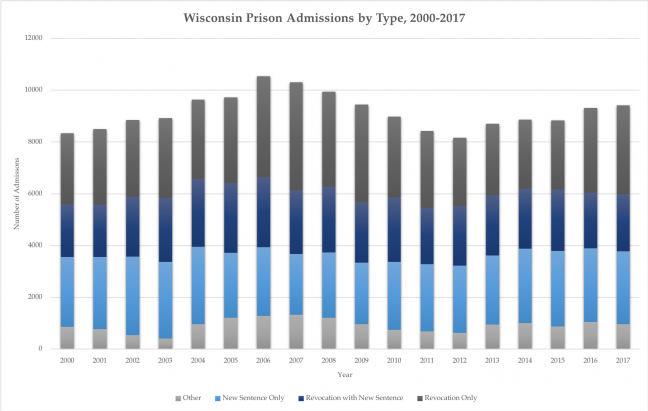

This is even more stark within Wisconsin. According to a Wisconsin Policy Forum report, in 2017, 36.5 percent of Wisconsin’s prison admissions were related to parole, probation or extended supervision violations — not new crimes.

“Re-incarceration for technical rule violations is a culture,” said Robert Agnew Jr., an organizer for JustLeadershipUSA. “It is a power tool that keeps Wisconsin’s prison population at its max and beyond max.”

The opportunity for parole violation is vast — the rules are extensive, and often not very straightforward. David Liners, state director for WISDOM, a grassroots organization seeking to end mass incarceration, explained that while some violations are pretty clear, such as failing a drug test, others, like borrowing money without proper permission, are less well defined.

“It’s hard to keep all these things straight,” Liners said. “In some cases, it is that people have messed up, but in that case, I don’t know that re-imprisonment should be the default way to deal with it.”

According to a recent report from the Columbia University Justice Lab, those under community supervision — a blanket term for parole and probation — comprise nearly 50 percent of the Wisconsin prison population, which has tripled since 1990, despite a decrease in crime rates.

Wisconsin’s Truth in Sentencing practices have majorly contributed to Wisconsin’s increasing prison population, but they have also played a large role in changes to Wisconsin’s community supervision system, according to University of Wisconsin professor emeritus of law, Walter Dickey.

Truth in Sentencing has led to the expansion of extended supervision, under bifurcated sentencing. Extended supervision is similar to parole, but it’s much more intense, according to Wisconsin Policy Forum spokesperson David Callender.

“Let’s say that you have three years on extended supervision,” Callender said. “If on the very last day you commit an offense and have to go back to prison, you could potentially go back for that entire three years. Generally, the longer that somebody is looking over your shoulder and the longer you’re under supervision, the more likely it is that you may do something wrong and end up back in prison.”

The evidence speaks for itself — the current system of community supervision isn’t working. This system, which was meant to lower the prison population, has only served to raise it. Rather than aid people with reintegrating into society in a positive way, this system only creates innumerable tripwires designed to keep people trapped inside a system which actively works against them.

“What that looks like on the day-to-day in our communities is 65,000 people invisibly shackled,” Agnew said.

And it’s not even helping the rest of the state. The Justice Lab report found that re-incarceration without a new crime costs Wisconsin taxpayers $147.5 million. Wisconsin lawmakers have shown time and time again just how willing they are to turn out their constituents’ pockets to send people to jail, with very little benefit to show for it.

The problem is that the purpose of community sentencing and of the prison system as a whole is poorly defined. It’s not clear whether the system is meant to keep the general public safe, or rehabilitate those who have committed crimes. As a result, the current system fails all around.

Rather than help those convicted of crimes learn and move forward, these tough-on crime practices just create more barriers preventing people from engaging with society in a positive way. And rather than helping to keep Wisconsin residents safe, they actually negatively impact society by keeping such a high percentage of the population in jail or on parole.

In the end, no one truly benefits.

Last September, the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, a philanthropic organization which has taken on a vast array of social issues ranging from criminal justice reform to drug pricing, announced a new initiative to transform parole and probation and actively work to reduce recidivism and revocation to prison.

Kelli Rhee, President and CEO of LJAF, highlighted the lack of positive impact the current system has. “Probation and parole failures contribute to exceptionally high incarceration populations, increased taxpayer burdens, and decreased public safety,” she said.

America’s “tough-on-crime” practices have gone too far, with very little positive impact to justify the system’s failures. In the interest of the safety and prosperity of all citizens — those who have been convicted of crimes and those who have not — we must redefine the system’s purpose, and redesign the system’s practices.

Rhee agrees there is ample room for improvement, and it starts with actively working to aid those trapped underneath the weight of the criminal justice system.

“If we can reform these systems so they better position people for success—providing access to mental health and substance use disorder treatment, for example—we will make an enormous impact on the justice system and individual lives.”

Cait Gibbons (cgibbons@badgerherald.com) is a junior studying math and Chinese.