In the increasingly solitary world we all find ourselves in, university students throughout the United States have learned to navigate the alienating world of Zoom classes, weekly COVID-19 tests and isolation. The defining characteristics of college life — lecture halls, football games and bars — are now things of the past. Students’ social lives are severely constricted. Will this have lasting psychological effects?

A study on the effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health from the Journal of Medical Internet Research found 86% of participants experienced increased stress and anxiety during the pandemic due to decreased social interactions.

Though it is difficult to accurately predict the lasting social effects, four psychologists at the University of Wisconsin wonder what ‘going back to normal’ will mean for students and how relationships and other social interactions will change in the long run.

“The one-liner is that isolation is fatal.”

In Roman history, exile was seen as the ultimate form of punishment, second only to the death penalty. Merriam Webster defines exile as the “state or a period of forced absence from one’s country or home.”

To UW Consumer Science Professor Christine Whelan, it seems we have all been individually exiled.

“Human beings need connection. When we are emotionally and socially isolated, we can experience psychological and physical effects from it,” Whelan said. “Humans need other people.”

This semester, students have felt this lack of connection in many ways. UW freshman Elsa Palmieri tested positive for COVID on Sept. 10 — less than two weeks into the first semester — and Palmieri said she felt isolated from a community she hadn’t even connected with upon entering quarantine.

“I was already trying to adjust to a completely new environment and being plopped into another new one was really hard. Even though I had a support system, it still felt like I was very alone in navigating being sick and starting college,” Palmieri said. “I was not physically alone, but I was mentally alone.”

At UW, some aspects of normal college life remain. Students can live in residence halls, dine in the cafeteria and attend the occasional in-person class. Yet, health guidelines prohibit most kinds of social interaction. Employees check student IDs at the entrance of certain dorms, only four people can sit at a table together in the cafeteria and in-person classes have to be small and spaced-out.

According to Whelan, it is college students’ nature to do exactly what they are currently told not to do — socialize.

“In terms of predictions for college students, the evolutionary imperative for humans is to do two things — survive and reproduce,” Whelan said. “The older people are trying to survive right now and the biological impulse of young people is to be social, be out there and party and you’re being told not to do that.”

In a landmark study by Harry Harlow in 1965 called “Total Isolation of Monkeys”, newborn monkeys were isolated in chambers for three, six and 12 months, respectively. Harlow found progressively debilitating effects as the period of isolation was extended. Ultimately, Harlow discovered with isolation comes social disability.

He found the ‘intellectual mind’ is far less crippled than the ‘social mind’ by prolonged total social deprivation.

But according to Whelan, the pandemic hasn’t crippled our social minds — it’s just kept them out of practice.

“If you think of being social not only as a need we all have, but as a muscle that may have atrophied a bit in the last year, then we can be kind to ourselves and push ourselves to reach out and resocialize when it is safe to do so,” Whelan said.

Relationships & Hookups & Friendships, oh my!

College students’ lack of social interaction may also lead to flimsier and more awkward relationships in the future.

According to Bradford Brown, a UW educational psychology professor, college friendships aren’t as strong as they would normally be right now and students may have to cling on to the first people they meet to maintain some level of social connectivity.

“This re-creation of social networks is really hard to do virtually,” Brown said. “There is an old phrase ‘beggars can’t be choosers’ and this is a year when one really can’t spend a lot of time trying to find the best people with which to establish lasting relationships.”

This could lead to weaker relationships and unhappy adult lives. According to the Mayo Clinic, friends play a significant role in promoting overall health and adults with strong social support reduce their risk of depression, high blood pressure and an unhealthy body mass index.

Brown also pointed out college is a pivotal time in people’s lives to build intimate relationships.

Approximately 28% of people meet their spouse in college, according to University Fox. These relationships are formed from college students’ complex social networks — which students can’t build right now.

“This is a time when individuals can venture out, experiment more and engage in a more sophisticated version of what they experienced in high school,” Brown said. “And if deprived of that, then it is just going to make individuals find it more awkward to develop the interpersonal skills that are going to be helpful in effective romantic relationships in the future.”

According to The Washington Post, students have found ways to cultivate virtual romantic-type relationships through “Zoom crushes” and dating apps like Tinder and Hinge. But it’s hard to further a relationship while adhering to social distancing measures.

Even students who do venture out on in-person dates face barriers. Palmieri said she finally worked up the courage to ask someone out last week and it didn’t go well.

“We were both wearing masks so I wasn’t able to hear half of his responses,” Palmieri said. “It definitely wasn’t the easiest interaction I’ve had.”

Dating has also gotten harder because most people aren’t doing well right now, as death, disease, politics and financial instability all exacerbate stress, according to Vox.

UW psychology Professor Paula Niedenthal compared intimacy during the COVID-19 pandemic on college campuses to intimacy during the HIV epidemic on college campuses in the 1980s and ‘90s.

“I would say HIV is the most similar to COVID for college students. For similar reasons, you can’t just mindlessly be intimate with people,” Niedenthal said. “We know people in similar situations have overcome the reduction of physical intimacy before.”

Ultimately, Niedenthal wonders how keeping six feet of distance will affect our instincts to touch each other.

The Peril of Deindividuation

Though masks and virtual gatherings prevent students from contracting COVID-19, these social distancing necessities also lead to a phenomenon Niedenthal calls ‘deindividuation.’

The American Psychology Association defines deindividuation as a state of loss of self-awareness and altered perceptions resulting in unusual and sometimes antisocial behavior.

“Our identities are either altering or disappearing,” Niendenthal said. “We have hidden behind so many deindividuation processes that we feel less connected to other people and that we are less of an individual with a particular identity in social situations.”

In a Vox article, Niedenthal said we tend to see emotions as more muted when the lower half of someone’s face is obscured. And if we cannot read each other’s emotions, how can we connect on an emotional level?

Freshman James McGuire said he feels uncomfortable when he can’t show his facial features.

“I feel awkward because I express myself a lot through my facial expressions and I can’t do that when I have a mask on,” McGuire said.

With 10% of universities fully online, many students have at least some of their classes on Zoom. Or, students have opportunities to take asynchronous classes, watching lectures and completing work on their own without a virtual classroom.

Brown said when students turn their cameras off in Zoom classes, teaching a virtual class is like performing with no audience.

“Anyone who performs before an audience relies upon feedback from the audience to know how to continue. When that feedback isn’t there it’s hard to meaningfully engage with people,” Brown said. “And if one learns to survive without those skills right now, they are harder to pick up in the future. So there could be long lasting effects here. We don’t know.”

A Gratitude Attitude

Isolation can link to depression, poor sleep quality, impaired executive function, accelerated cognitive decline, poor cardiovascular function and impaired immunity at every stage of life, according to the APA.

University Health Services offers virtual mental health services including individual counseling, group counseling, psychiatry and 24-hour crisis services for students who are experiencing the adverse effects of isolation. Students can find more information on how to connect with UHS on their website.

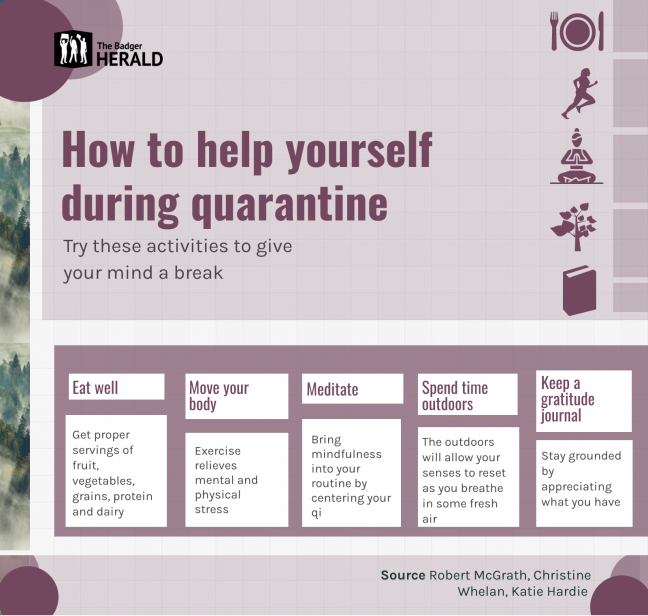

UHS is seeing an increase in requests for their services, but say it’s important students also explore other methods of stress relief. UW psychologist Emeritus Robert McGrath emphasized the importance of appreciation and suggested students keep a gratitude journal to help stay grounded.

“A gratitude attitude is crucial. When you are under stress, you aren’t appreciating the good that is going on,” McGrath said.

McGrath also suggested eating well, moving your body, meditating and spending time outdoors. While these suggestions may seem self-evident, studies support them. A Yale ecopsychology article says spending time out in nature can reduce feelings of isolation, lower blood pressure, enhance immune system function, increase self-esteem, reduce anxiety and improve mood.

Whelan also stressed the importance of the outdoors and recommended going for a walk with someone.

“Go for a walk outside,” Whelan said. “In fact, going for a walk with a friend is probably the best thing you can do every day because there is sunlight, you are moving and it will really boost your mood and well-being.”

In the end, nobody knows what the long-lasting psychological impacts of prolonged isolation will be. Psychologists such as Whelan, Brown, Niendenthal and McGrath can make predictions based on past studies and historical events, but only to an extent. Long-lasting effects from weak relationships, deindividuation and isolation may persist for unknown periods of time.

“The key things I wonder about are how long this carry over [will] last, what kind of information will it take to go back to normal — or construct a new normal that is satisfying for everybody — and are we going to do that quickly or over time,” Niedenthal said.