A scientific breakthrough had the whole physics community on the edge of their seats Thursday morning, when National Science Foundation announced the observation of gravitational waves caused by a merger between two black holes.

Einstein predicted 100 years ago that space and time are woven together in a space-time fabric that can swing, vibrate and transmit waves, Sebastian Heinz, University of Wisconsin astronomy professor, said.

Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), a highly sensitive, large-scale physics experiment designed to detect gravitational waves, has allowed scientists to finally observe Einstein’s theory of gravity after years of countless calculations, Heinz said.

“It’s basically like sound waves except that it’s space-time itself that vibrates,” Heinz said. “It’s something fundamental to the theory of gravity.”

LIGO, sponsored by National Science Foundation, is the joint effort of about 1,000 scientists from around the world, with most of them in the U.S. A group of scientists from Massachusetts Institute of Technology and California Institute of Technology developed the idea in the 1970s, and began officially operating it in 1999.

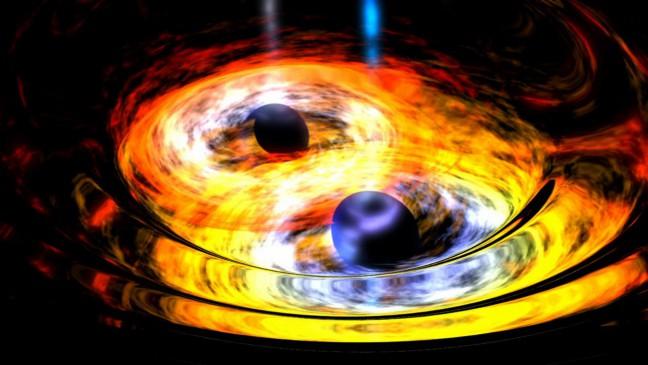

The two black holes of roughly similar mass and close proximity are orbiting each other like the earth orbits the sun, Heinz said. In a process Heinz described as “spiraling toward collapse,” they run into each other and merge into a single black hole with approximately twice the original size.

Heinz said a massive object like a black hole that oscillates in space or orbits around another body, will send spacetime ripples, or gravitational waves, propagating close to the speed of light.

“When you have two black holes, they have basically the highest concentrations and bending of spacetime fabrics that Einstein discussed,” Heinz said. “When the black holes orbit each other, it’s like having a violin string or guitar string. If you pluck it extremely hard and extremely fast and sit across the room [from it], you can hear the vibrations from that echo.”

Peter Timbie, another UW physics professor, said the discovery of the black hole merger will lead to observations of a similar nature.

“The neat thing about this discovery is that it’s really just the beginning,” Timbie said.

In fact, Timbie said the LIGO team announced they are likely to see another black hole merger every two weeks. The team is even planning to make LIGO several times more sensitive, Timbie said, which means they’ll likely see similar events not only more frequently, but also farther away in the universe.

At the NSF press conference, Timbie said the researchers made the analogy that this observation is like a deaf person suddenly being able to hear.

Timbie said while most cosmic discoveries are revealed through light, such as with telescopes, the merging of the two black holes equates to hearing a violent collision.

UW-Madison scientists are excited about the breakthrough, Timbie said, but the university is not putting forth a large amount of energy into this field of research because about 20 scientists from UW-Milwaukee are already part of the LIGO collaboration.

While scientists haven’t found the best way to apply the theory to the benefit of the general public, Timbie said, it is a groundbreaking discovery in the field of physics and astronomy.

“It’s inspiring. It is like being able to see the world with a brand new set of eyes,” Timbie said.