Two distinguished University of Wisconsin faculty members received the prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship to bolster future research efforts in the humanities.

The Guggenheim Fellowship awarded its prestigious award to two professors from the University of Wisconsin this year.

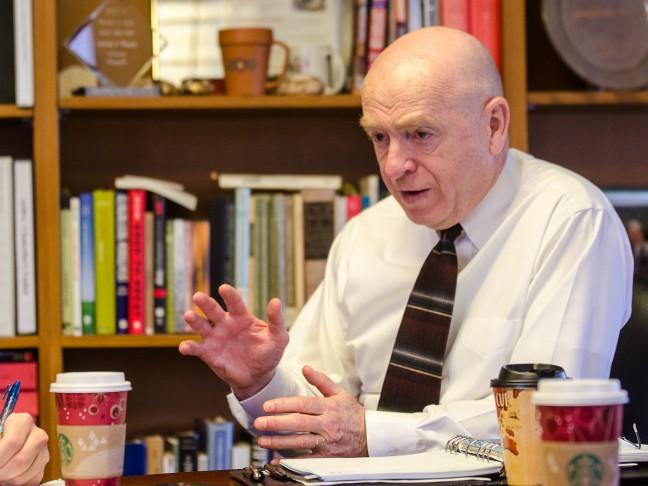

Deborah Brandt, professor emerita of English, and Lynn Nyhart, professor of history of science, were both named fellows for their distinguished works and promise of exceptional work in the future.

A statement from UW said the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation selected the two faculty members from a pool of nearly 3,000 applicants and has granted $290 million in fellowships since 1925.

Brandt received the fellowship for her work in composition theory and mass literacy, an area she said involves everyday experiences people have with writing.

“More and more, writing is becoming a bigger factor because of the change in the kind of work we do,” she said.

She also said technology has played a large role in the changing perception of writing and invites writing in leisure hours. People are increasingly choosing to communicate using technology, she said.

Her interest in what this trend meant to people and how it affects them was why she entered the field, she said. When she first entered UW, she taught writing but gradually wanted to understand the bigger concepts behind the field and the context of being a writer in relation to the wider world.

Since she has retired from teaching, Brandt said she plans to focus her time on a book.

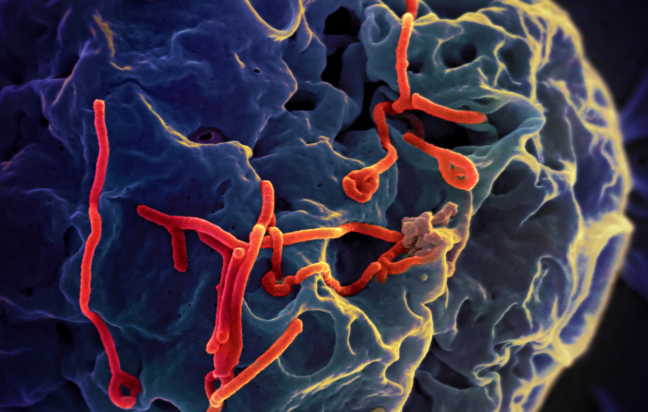

Nyhart also received the Guggenheim Fellowship for her study of biological individuality, a field that aims to understand exactly what constitutes an organism. She cited the example of a strawberry plant, which sends out individual vines from its main body and often break from the main plant, as an example of the area of study.

While determining the separateness of natural entities can be difficult, she said this differentiation is easier in humans.

“For us, we’re borne of one object that continues on through maturity and death,” Nyhart said. “It’s pretty easy to consider ourselves individuals.”

However, there are many organisms that go through more complicated life cycles – such as coral, that are built of several different organisms that combine to form a single organism. Marine invertebrates that use asexual reproduction are also subjects of her study, Nyhart said.

Her project, which was done in conjunction with the Chicago Field Museum, focused on the effects of science and biological individuality on the questions facing Europe in the 19th century as it began rapid modernization.

She said the question involves how the language of governance went back and forth between biology and political economy.

Earlier this year, Nyhart was also the recipient of the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation’s Kellett Mid-Career Award, given to outstanding faculty members five to 20 years past tenure.

Following her fellowship, Nyhart plans to work more on her project after taking a semester-long leave from teaching at UW. She said she plans to visit the archives in London, Paris and Germany to see what the scientists of the 19th century thought about biology.

“In the humanities, the chance to go and do research happens through a collaboration, and UW has been very generous in helping to support this project,” she said.