The public’s regard for scientists in media has changed since before the COVID-19 pandemic, according to professor in the University of Wisconsin Department of Life Sciences Communication Nan Li.

In early TV shows, writers assembled the stereotypical form of scientists many are familiar with — white, male, old and villainous. That image also evolved into a more geeky portrayal in contemporary shows like The Big Bang Theory.

The recovery stages of the pandemic opened up new perspectives for scientist portrayal in different media, Li said.

“When COVID happened, the images were somewhat revamped to the extent that a lot of people either think scientists are [not doing] crazy things, but still some of the things that don’t really help,” Li said. “But on the other hand, a lot of people see scientists as heroes because they’re definitely inventing vaccinations and they’re doing all of this research that helps us deal with this new pandemic.”

Life sciences communication professor Dietram Scheufele said the shift from broadcasting to today’s narrowcasting — or news tailored toward a specific audience — means there are many ways to convey one image of a scientist, depending on the target audience.

But from the start, the old, white, male scientist image took off. While the stereotypical scientist underwent some image changes over the years, it continues to be ingrained in people’s minds. Scheufele said this has led to an American public thinking they know what a scientist looks like, when their idea is solely based on what they’ve encountered in the media.

In fact, some Americans have never so much as interacted or been in direct contact with science, Scheufele said.

Department chair of life sciences communication Dominique Brossard said entertainment media’s decision to continue with these narrow-minded scientist stereotypes is harmful to the overall perception of scientists and the ability to reach to an audience.

“[Shuri] from Black Panther was 15 years old, a Black female scientist and she saved the world,” Brossard said. “Anecdotal evidence shows that there’s a lot of African American kids that went to see this movie and that shows kids this person looks like me — I could become one of these people. That was one of the first movies to portray young female black scientists in that position of power.”

Initiatives such as The Science and Entertainment Exchange are working to reverse some of the stereotypical portrayals.

For example, Natalie Portman’s character, Jane Foster, in the Thor movies was originally supposed to be a nurse, Brossard said. Foster’s position as a nurse could have suggested she reported or worked under the advisory of a male doctor, and this dynamic could have perpetuated gender stereotypes. To remedy this problem, the writers made Jane a physicist instead.

In a study of Twitter discussions around the movie’s release, Brossard said investigators examined how the public perceived Portman’s character and if they were surprised she was a physicist.

“We found that in the discussion around the movie, nobody says this woman shouldn’t be a top scientist,” Brossard said. “They say more positive views of importance to show gender and diversity in scientists.”

Science as a field is also diversifying, both in terms of different scientific specialities and how people communicate it, Li said.

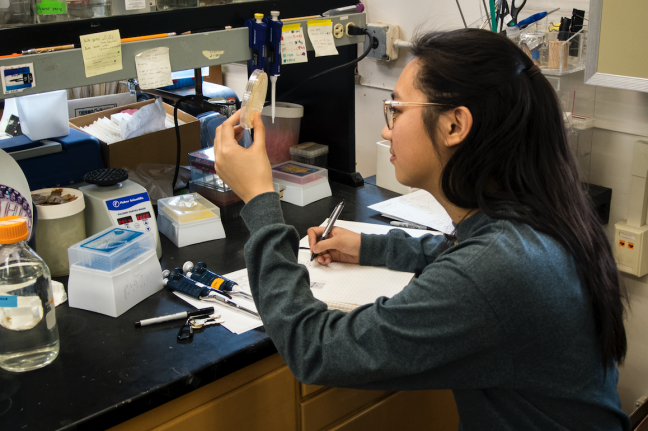

With social media today, Li said people can now see the face behind the science as scientists conduct their own communication alongside their research.

“A lot of scientists are doing their own communication,” Li said. “They’re trying to reach out on their own to little niche audiences. You see many different types of scientists doing comedy shows, comics or podcasts. They are trying to reach out to different audiences and present themselves directly.”

Outside of scientists in entertainment media, real scientists are often regarded differently, since the public places differing amounts of trust on different areas of science across the board, Brossard said.

Scheufele said communication scientists have also observed a shift over time in how and why people say they follow science. Today, a person choosing to say they follow science has become a partisan statement rather than a statement which used to indicate an “enlightened democracy,” Scheufele said.

Li, Brossard and Scheufele said this shift comes down to people experiencing new social factors, like the pandemic or politics.

“Trust in scientists in a specific context will depend on how much interest you have in an issue, how much you know you consume science media, what are your worldviews, perception of the risk and benefit for this issue,” Brossard said. “For example, if you talk about an environmental issue, how do you feel about the environment? What is your perception of the risk and benefit for this issue?”

On top of the partisan divide over science, there’s a battle with misinformation.

“There’s a lot of misinformation out there, but we don’t know the extent to which that misinformation convinces people or changes their views,” Brossard said. “Because what we know is that people tend to find the science that supports their belief.”

For communication scientists, factors like misinformation — though tough to address — show science is not set in stone, Brossard said. For example, new information during the inception of the pandemic has evolved, and some question whether the outdated science is misinformation today.

First ever sustainability seminar displays multiple disciplines working in sustainability

But, other than misinformation, Brossard said there is a bigger threat to science — the disconnect between public opinion dynamics, scientists and journalists. Scientists are answering what they think the public should be asking instead of the questions being asked, Scheufele said.

What it comes down to now is bridging that gap, which communication scientists like Li, Brossard and Scheufele target in their research.

“Now, you have all the disciplines, organization and philanthropy, everybody realized that communication is extremely important, and not only communicating in one way, but that feedback of understanding how people on the other end feel,” Brossard said. “It’s not just me telling them, but it’s me talking to someone; someone telling me things. And that exchange will build up good science communication, so that’s really like being quite amazing to see.”