A new series of studies from University of Wisconsin researchers found some reasons why stereotypes can be hard to get rid of despite having no supporting evidence.

In the series, UW researcher in the Department of Psychology William Cox investigated why stereotypes are so difficult to overcome. Stereotypes are perpetuated through self-reinforcement. The brain uses them to fill in information about unfamiliar people.

“Our brains are designed to learn sometimes from limited amounts of information,” Cox said.

This limited amount of information leads people to fill in the gaps through stereotypes.

Psychology professor Markus Brauer with the Brauer Group Lab researches psychological processes related to discrimination, prejudice and stereotypes. Brauer said the human brain has a tendency to form stereotypes because of the way it’s hardwired.

The human brain has to simplify its physical environment by creating categories, Brauer said. By placing things into these categories, the brain can associate traits and characteristics with them.

Though learning from limited information can be useful, it can create inaccurate beliefs about other social categories, according to Brauer.

“We use somebody’s membership in a group to make predictions about how they are going to behave,” said Brauer. “The problem is we tend to then overgeneralize, and we think group membership is more diagnostic of their behavior than they actually are.”

Stereotypes may reduce opportunities and create biases, prejudice and discrimination against those of the stereotyped group, according to Cox. To understand human beliefs in stereotypes, Cox and his colleagues investigated further.

Cox and his coauthors, Xizhou Xie and Patricia Devine, performed three studies to determine how much people learn when their stereotypes are confirmed, disconfirmed or unchallenged. In a follow-up study, the investigators wanted to determine if a participant misremembered their stereotype as being validated in times when it was disconfirmed.

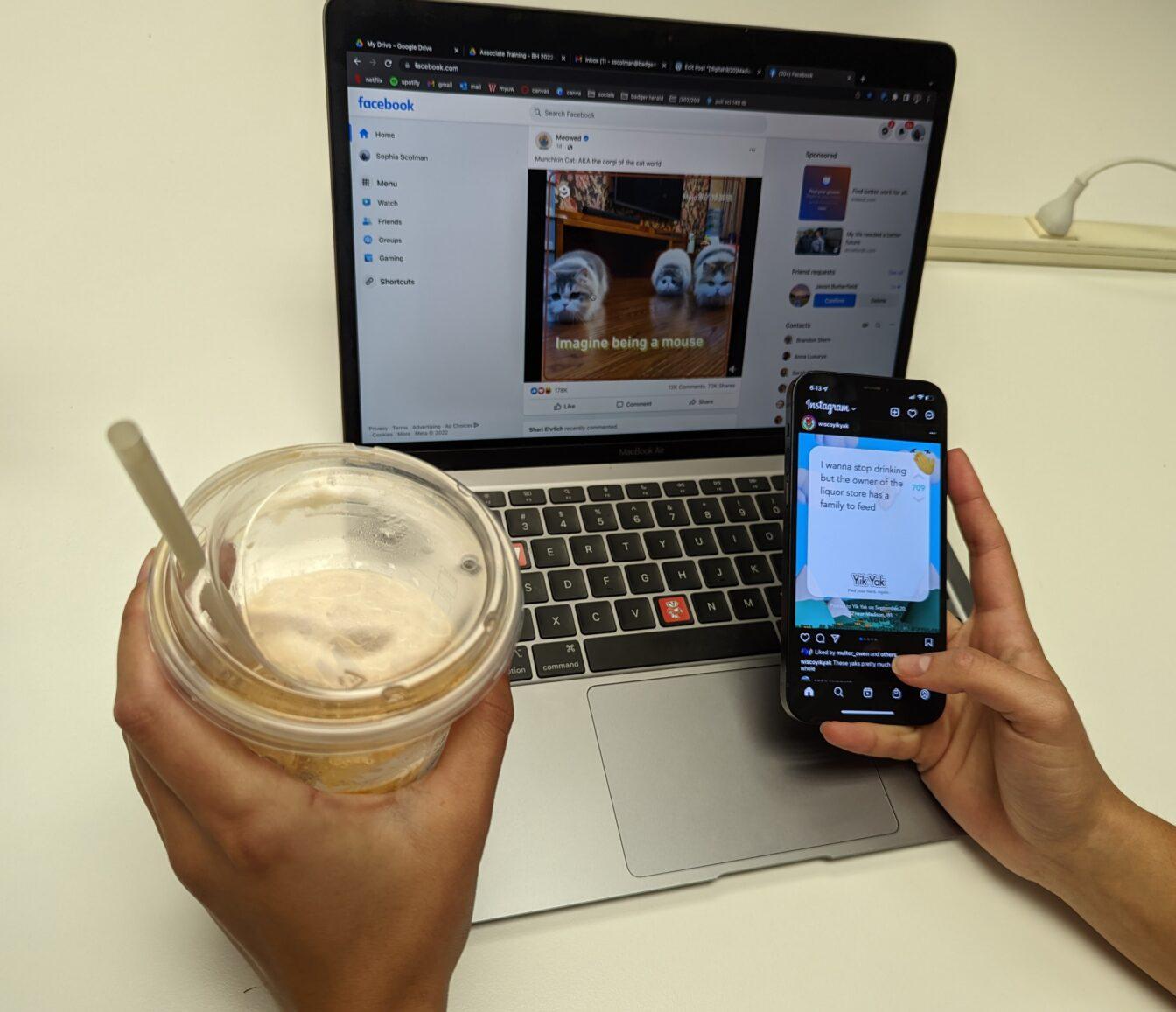

In studies one and two, participants were split into stereotype confirming, stereotype disconfirming, or no feedback conditions. They were instructed to view various social media profiles of men to determine whether they were gay or straight based on the interest stated in the profile. Each social media profile was also assigned to state interests in one of three areas of either shopping and fashion, sports or neutral interest.

After making a conclusion, participants received feedback according to their group’s condition.

According to Cox, both studies indicated that participants who received stereotype-confirming feedback stereotyped more over time, while participants who received disconfirming feedback stereotyped the same amount over time.

People within the disconfirmation evidence group did not learn from the evidence provided about their stereotypes. Even by receiving feedback stating they had made the wrong conclusion, those participants didn’t change what they thought. Previous research on confirmation bias may explain this, Cox said.

“We have this crazy tendency that’s called confirmation bias,” Brauer said. “Once we sort of have a belief of a category, including a social category, we are on the lookout for evidence that confirms that belief, and we tend to disregard evidence that contradicts that belief.”

In Cox’s study, the group of participants who received no feedback stereotyped more over time, meaning participants reinforced their own assumptions in the absence of evidence.

The third study was to determine whether participants misremembered feedback on a judgement and whether they misremembered the feedback to be stereotype-confirming.

In the third study, approximately 300 participants received feedback after making a judgment. The participants were shown the profiles a second time and asked to report what feedback was received.

When participants misremembered the feedback, approximately 60% falsely remembered the feedback to be stereotype confirming, according to Cox’s study.

For Cox, learning from untested assumptions is thought to be linked to Hebbian mechanisms, or the tendencies of the brain to learn through association. According to Cox’s study, when a person stereotypes, this is thought to strengthen the neural connections that form the stereotype.

If a person does receive feedback and that feedback confirms the stereotype, a reward signal pathway is activated in the brain, according to Cox’s study. But when a person receives disconfirmatory feedback, previous associations due to Hebbian mechanics interfere with new learning, weakening the effect of disconfirmatory evidence.

Social groups are another factor that can influence perceptions and beliefs about others. People tend to associate with others who share similar beliefs to gain social validation for having those beliefs, Bauer said.

By identifying with others’ beliefs, stereotypes and biases can be encouraged through confirmation bias and validation from peers.

“It is so incredibly important to change the social norms around inclusion and discrimination,” Bauer said. “People are incredibly susceptible to what is happening around them and what other people think.”

Changing the social norm from being influenced by biases and stereotypes to becoming more inclusive could impact the behavior and perceptions of others, Brauer said.

Other research completed by the Cox Lab has shown people can overcome the automatic processes that perpetuate stereotypes if they receive active intervention against the stereotypes.

Deconstructing stereotypes cannot be a passive process, Cox said. It must include engaging people as active agents of change in overcoming the bias.