Wisconsin and Oregon have more in common than most residents of the states would admit.

Both have one major city accompanied by mid-sized cities dotted throughout the state, a wealth of natural resources in a wide back country and a public flagship university that fulfills dreams for in-state and out-of-state students.

And both those flagship universities are proposing radical changes to the way they are governed and funded.

Last year, University of Wisconsin Chancellor Biddy Martin introduced a version of the New Badger Partnership, an item in Gov. Scott Walker’s budget that allows for the separation of the Madison campus from the rest of the UW System.

The proposal, known in policymaking circles as the ‘public authority model,’ would also establish a new Board of Trustees solely for UW and break the campus off from the Board of Regents.

The University of Oregon faces a similar proposal today that could be indicative of the future of Wisconsin’s debate.

According to Jenna Beier, a spokesperson for Rep. Chris Harker, a Democrat from Portland’s suburbs who supports UO’s “New Partnership,” the debates surrounding the New Badger Partnership in Wisconsin and the Oregon model mirror each other.

With Oregon’s flexibility proposal further along in the public debate than the New Badger Partnership, its successes and failures could be indicative of what’s coming for UW officials in the next year.

The New (Duck) Partnership

Under the New Partnership, UO officials are collaborating with Democratic Gov. John Kitzhaber to change the university’s funding and governance structure.

“[Kitzhaber] has proposed a fundamental Pre-K through 20 educational reform package, and our efforts are coordinated with the governor’s efforts to change all governance,” said Michael Redding, a spokesperson for UO.

Redding said Kitzhaber plans to reorganize Oregon’s entire educational system into one governance board that would regulate all educational institutions beginning in kindergarten and ending with higher education.

UO would still be granted more governance autonomy, however.

Similar to the New Badger Partnership, the Oregon proposal would create a new governing authority for the university so decisions would not need to be held at the mercy of the state.

The new local UO board would give more autonomy to Oregon’s flagship institution, not unlike the Board of Trustees that would govern UW if the New Badger Partnership becomes law.

But the Oregon board would still be subject to regulation from the state’s board of education, especially on matters such as tuition hikes. Under the Oregon partnership, any rise in tuition exceeding 5 percent would need to go to a vote in the state Legislature.

Beier said public universities in Oregon are still not satisfied with the proposal.

“The smaller, less financial aid, more independent universities are not going to go down without a fight,” Beier said.

Because of differences between lawmakers and UO officials and a wide range of opposition to the proposal, the New Partnership proposal died in the current session of the Oregon Legislature.

But the controversy over the New Partnership’s implementation continues today. UO officials and legislators have gone back to the drawing board and are tweaking the legislation to make it more appealing in Oregon’s statehouse.

Beier added making small tweaks similar to the ones UO made to their model – such as the 5 percent tuition cap – could be helpful for UW administration officials hoping to make their proposal more palatable to the Wisconsin Legislature.

So far in the New Badger Partnership’s approval process, Chancellor Biddy Martin and other administrators have not said they are willing to make any significant changes to the public authority model as it stands today.

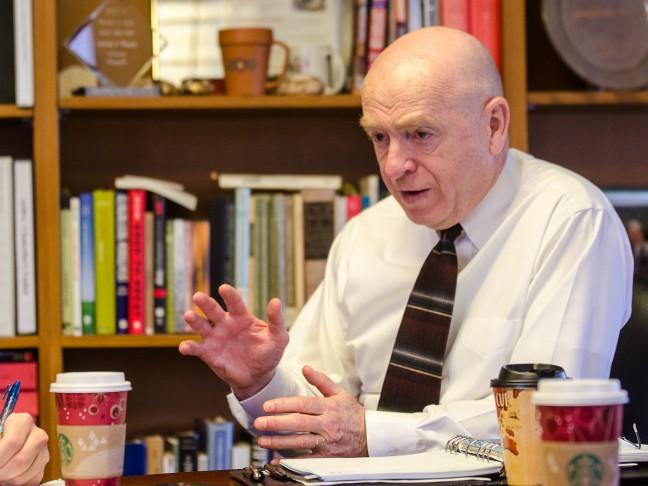

In fact, UW Vice Chancellor for Administration Darrell Bazzell said he expects the UW System to make more concessions for governance.

“[Governance] is a very tough issue,” Bazzell said. “You’ve heard the chancellor express a strong desire to have a local board. We’ve not yet heard… a willingness to pursue that type of model.”

A different student government reaction

The Associated Students of the University of Oregon, UO’s main student government, has opposed the proposal and clashed with the administration throughout the past academic year, ASUO President Amelie Rousseau said.

Like critics of the New Badger Partnership, Rousseau said the Oregon proposal would put too much money in the hands of a non-transparent foundation. Also similar to criticism of Wisconsin’s model, she said the partnership would raise tuition rates and make UO less accessible for all students.

“We think that this is a move towards deregulating our university and making it less accessible for Oregonians to come,” Rousseau said. “It’s been a big fight, but it’s a fight worth fighting.”

ASUO’s decision is much different than the Associated Students of Madison’s decision last month to endorse the New Badger Partnership.

ASM Vice Chair Beth Huang said the new council will likely vote to support or oppose a specific aspect of the New Badger Partnership, such as splitting from the UW System, as early as next week. Huang added she would not be comfortable calling for the vote if a significant number of council members were not at the meeting.

Unlike ASM, whose members between the 17th and 18th sessions have roughly split on the New Badger Partnership, ASUO almost unanimously voiced their opposition to the Oregon model.

“We saw the New Partnership as something that would be harmful and compromise other schools too,” Rousseau said. “It wasn’t really a contentious decision.”

Legislative woes

Opponents of the New Badger Partnership have been highly critical of Martin’s relationship with Walker and members of Wisconsin’s Legislature. Not long after Walker introduced the public authority model in his biennial budget, a new lobbying group called Badger Advocates quickly formed.

Brandon Scholz, a spokesperson for Badger Advocates, said the group has the best interests of UW in mind.

“We were formed to support the university and the proposal in the budget that would help Madison achieve autonomy and public authority,” Scholz said. “We thought it was important to have resources outside the university that supports what the university does.”

Scholz said since UW only has one lobbyist, the administration needed more voices at the Capitol, prompting the formation of the group.

Rep. Steve Nass, a Republican from Whitewater and the chair of the Assembly Committee on Colleges and Universities, said he noticed an uptick in lobbying activity to members of the Joint Finance Committee not long after Rep. Robin Vos, R-Rochester, suggested the public authority model might not make its way out of committee.

“Once it was known that there was a good likelihood it would be pulled from the budget, they showed up on the doorstep,” Nass said.

In Oregon, university officials have a larger team of lobbyists who are working with lawmakers on a new proposal for the next legislative session.

Officials in both states have said the dispute over new public authority models is not split down partisan lines. In Wisconsin, both Nass and some of Dane County’s most liberal political figures have voiced their opposition or support for the partnership.

Oregon’s House of Representatives currently has a 30-30 split, accompanying a 16-14 split in the Senate.

Although many businesses in Wisconsin and Oregon have said they support each respective proposal, no pro-business or anti-business partisan line has formed around the new flexibility.

And although many UW students have protested the New Badger Partnership because they believe Martin has collaborated with Walker too much, Rousseau’s student government has clashed with Kitzhaber’s Democratic administration and some Democratic representatives over the proposal.

“Originally they didn’t want this to be a partisan issue, and so they were very careful to not gain the public support of one person versus another,” Rousseau said. “I don’t necessarily think this is a partisan issue, I think it’s deeper than that – it’s more complicated.”