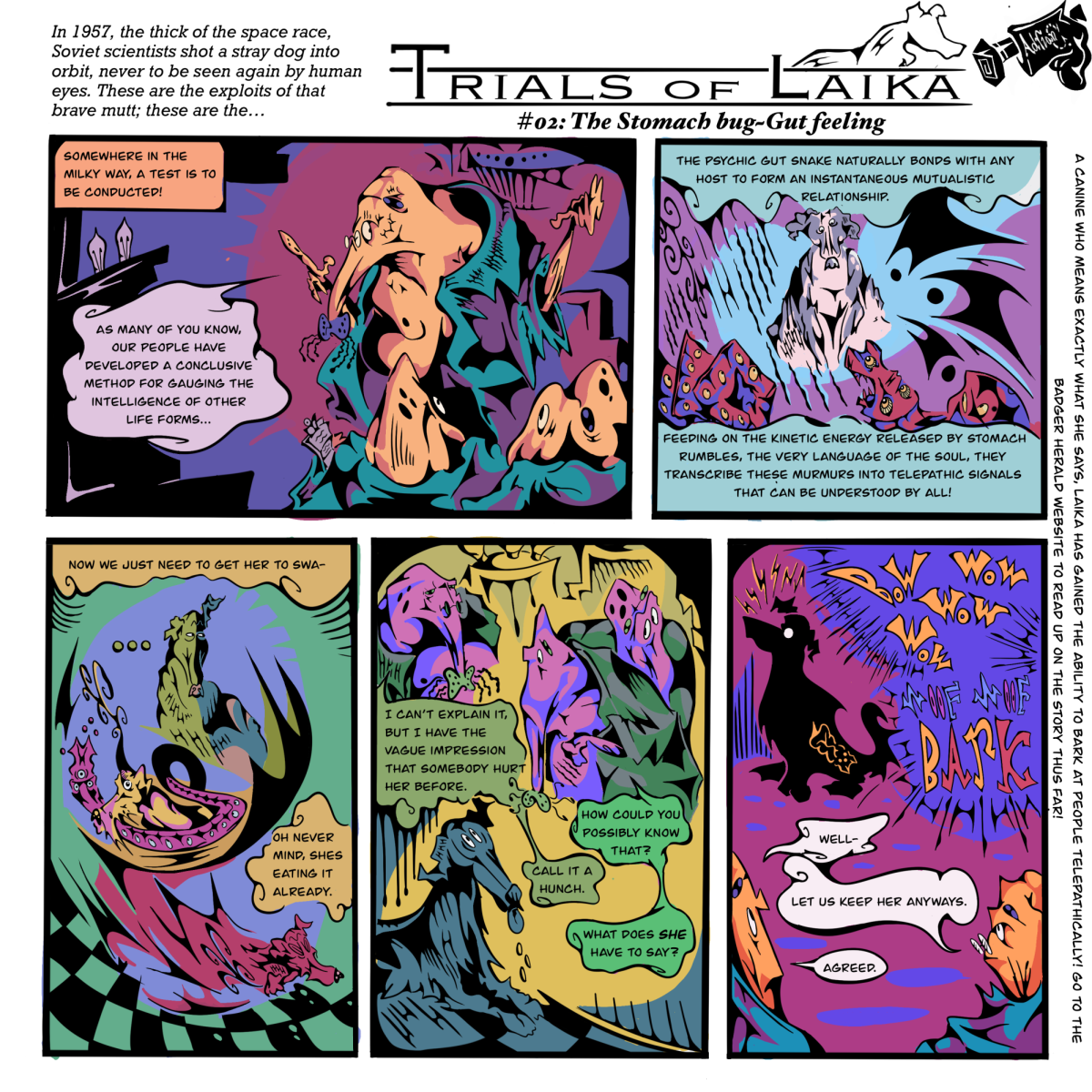

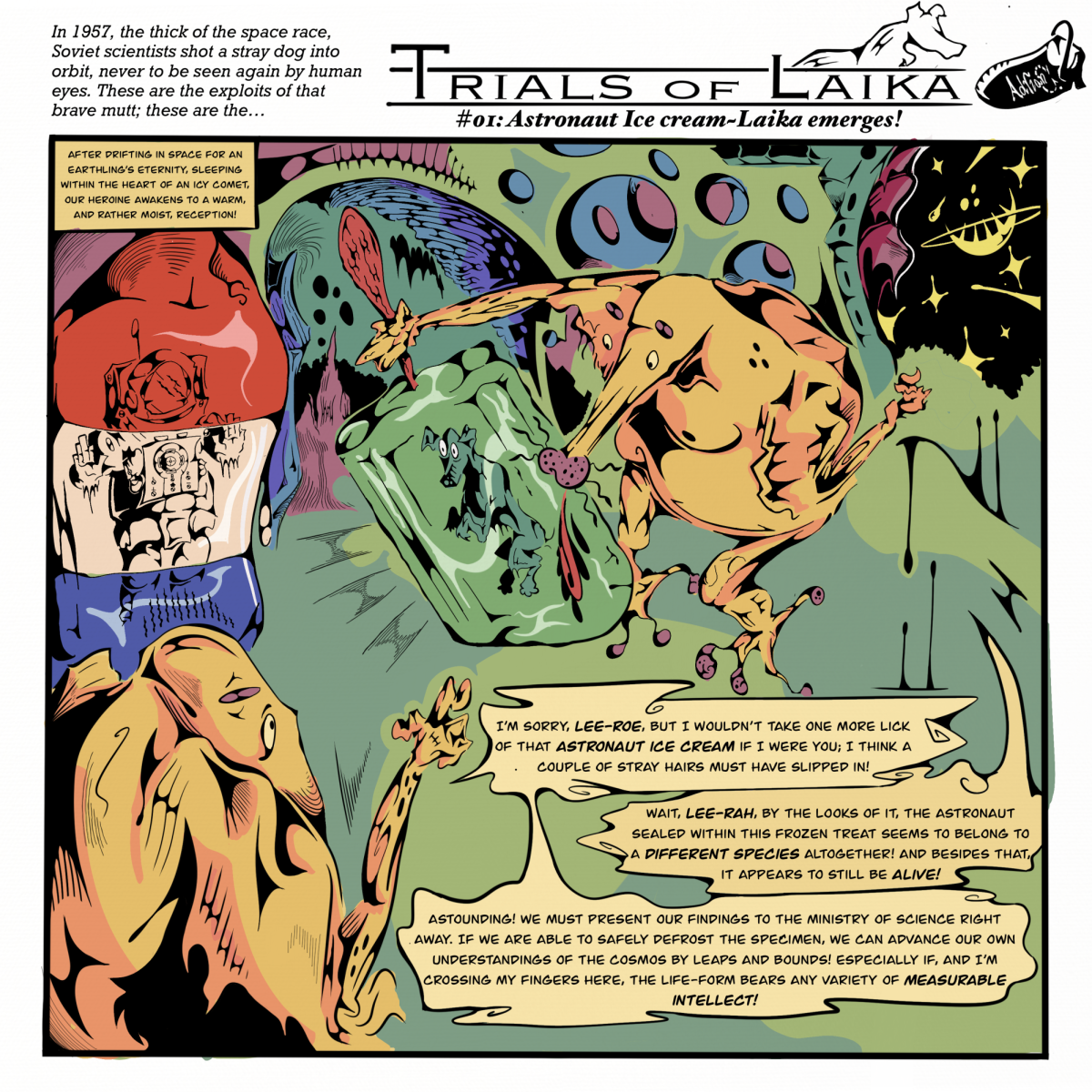

For five brief years, the University of Wisconsin sported one of the greatest voyages in modern western education.

Housed in sleepy Adams Hall on the shores of tranquil Lake Mendota, 327 students between 1927-32 willingly enrolled themselves as guinea pigs in a remarkable divergence from the traditional university system, known famously as the Experimental College.

Courtesy of Wikipedia

Only a two-year program, the Experimental College took what the current university system accepted as a liberal education, and challenged or rejected it, according to the Wisconsin Magazine of History. Students in the program were free from semesterly grades, regimented schedules, compulsory classes and formal teachers. They instead dove into self-exploration, rewarding debate and deep and powerful reflection on some of the greatest questions humanity has faced.

Courtesy of Wikipedia

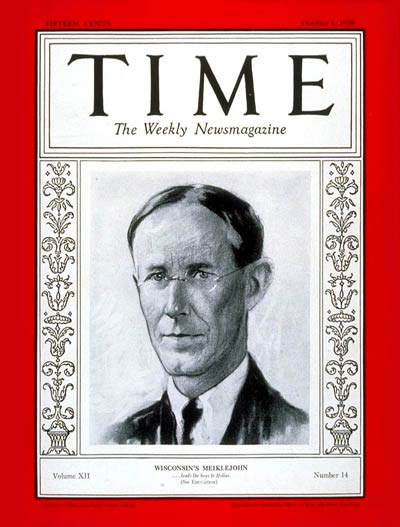

Its founder, Alexander Meiklejohn came to the UW in January 1926, after Glenn Frank, his equally progressive and robustly imaginative counterpart and recent university president invited him. Previously the president of Amherst College, Meiklejohn wrote a detailed article for Century Magazine summarizing his revolutionary idea for a new form of higher education. The exciting potential of Meiklejohn’s proposed institution struck the then editor-in-chief, Frank. When Frank strode into office as head of UW, he welcomed Meiklejohn to open his bold brainchild on campus.

Meiklejohn accepted the Thomas E. Brittingham chair in philosophy and became an extraordinary hit on campus. His progressive and provocative teaching style aroused cheers from excited students. While continuing to lecture, Meiklejohn began his mission.

As Meiklejohn saw it, the true meaning of an education had been eroded and withered away by university’s obsessions with research. Teaching had become secondary, on the “tail end of the comet.” While modern institutions offered many classes within a large scope of subjects —insinuating that any subject properly studied constituted a liberal education and well-attuned citizen — Meiklejohn felt they failed to teach students the basis of true intelligence. Students needed a college that fostered a true and genuine education, somewhere to think, to ponder and to eventually understand him or herself and the society in which he or she lived.

Courtesy of Wikipedia

The Experimental College opened in 1927 with a class of 119 students and less than a dozen hand-selected faculty. Coursework revolved around the thorough study of great books and a holistic study of human civilizations, specifically ancient Athens and the 19th century U.S.

“It is, however, perhaps worth remembering that once upon a time it flashed upon the view of a later Western Europe and gave to it the greatest educational impulse that the later Europe has had. We are daring to believe that genuine contact with Greek thought and appreciation and expression would bring to American youth in our colleges in somewhat the same way the beginnings of an intelligent study of the things which are worth studying.” Meiklejohn on ancient Athens

Freshmen studied the great minds of Greece — Plato, Aristotle, Homer and Thucydides to name a few. Through these timeless historical figures, Meiklejohn hoped to impart the eternal and powerful moral questions transmitted through ancient works, ideas and questions — eventually determining the fundamentals of goodness, justice and truth. Students did not study the civilizations in a chronological sense, but instead the epoch’s questions of philosophy, government, literature and drama.

“They, like ourselves, were facing the human situation, and they made one of the great attempts at understanding it. It would be good for a freshman to lose himself in that attempt.” Meiklejohn

Sophomores would then use their knowledge of an ancient civilization to better understand the more contemporary 19th-century U.S. civilization. As Meiklejohn felt, the powerful institutions and exact sciences of modern thought did not dominate and shape the Greeks, and in effect their logic and ideas were much more pure and free — fit for studying.

Courtesy of Wikipedia

Were the weighty questions of humanity proposed by the Greeks ever answered? What intrinsic values and ideas do humans share regardless of the time they lived? What is good and evil? These were the questions students of the Experimental College attempted to answer.

“And, further, we think that out of these two views of Western civilization, first at its beginnings and then at its next to the latest point, the student would get a sense of the human process as a whole. He would see that life has determining conditions and that their effects are definite and continuous.” Meiklejohn

The coursework was peculiar, but the university tolerated it. As long as students took one outside course in the regular university, the two years spent in the Experimental College counted toward college credit. Instead of traditional teachers, the Experimental College featured a number of advisors who lived with the students and taught through tutorial lessons preparing them for future study within the traditional university.

Courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society

Advisors directed student’s thinking, and through Socratic debate helped them form personal and educated opinions of the world around them.

“I don’t believe that some people are unfit for college education. College education should be so contrived that it is fit for everybody.” Meikeljohn on higher education

After its first year, enrollment in the college continually declined. The economic downturn of the Great Depression caused the university to double its tuition, and overwhelming public desire for the traditional college experience and poor public image hamstrung Meikeljohn’s lofty goals.

The nation viewed the Experimental College as a hotbed of radicalism. Students dressed peculiarly, were very politically active, rambunctious and outspoken. The college sported three times the breakage in dorm assets, a very active communist cell and numerous accounts of disruptive shenanigans.

In April 1932, Experimental College advisors proposed an expansion of the college to accommodate both genders. But the proposed plan faltered. Tension between the College of Letters & Science Dean George Clarke Sellery, Meiklejohn and Frank caused a hiccup in administration, and the faculty and regents voted to end the college in May 1932 and by June its doors were forever shut.

While the Experimental College was brief, its implications for the American educational system are powerful. Especially now, when students are reduced to quantifiable grades and numbers, marginalized and routinized, and subjects are briefly, furiously memorized only to quickly dissipate, it is grounding to remember there is much more to, and could be made of, education.

Either way, while you stress for finals, remember, Experimental College students would be kicking-back on lakeshore, reading Plato’s “The Republic” and discussing big moral questions.