Elizabeth received a surprise package on her birthday last July: A letter confirming the $4,000 settlement she reached with the Recording Industry Association of America had been successfully paid.

It felt good to know her legal troubles with illegal downloading were finally over, but at the same time, the reminder of the ordeal was “kind of a downer,” she said.

The University of Wisconsin junior, who asked that her real name be withheld for fear of further prosecution, was one of the 16 University of Wisconsin students threatened with a lawsuit in March after the trade group representing the major U.S. record labels identified filesharing activity from her IP address.

“I wanted it to go away,” Elizabeth said. “I didn’t want to be studying for finals and have that in the background.”

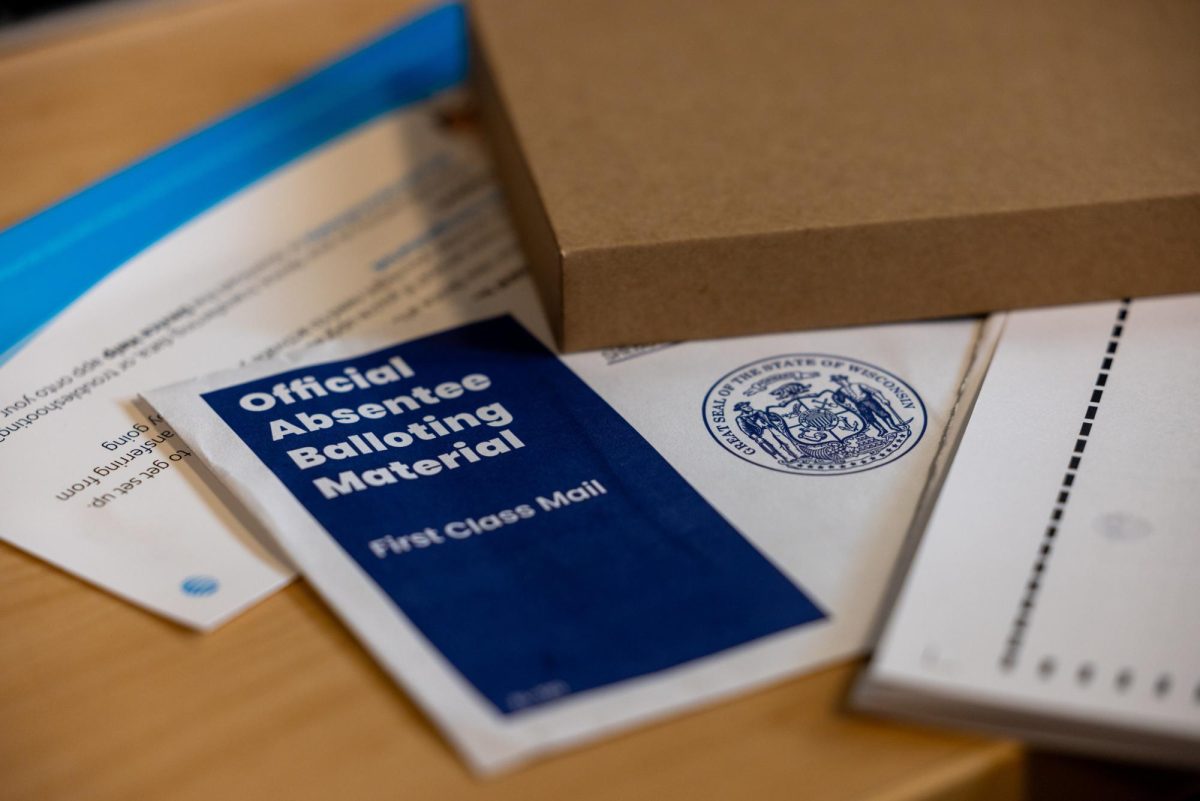

Elizabeth’s settlement was part of an RIAA campaign against music piracy on college campuses that began with the mass mailing of settlement letters to unidentified network users at 13 universities on Feb. 28. Most recently, the University of Wisconsin System received 62 settlement letters on Sept. 19, 28 of which went to UW.

The letters notified the individual of an impending lawsuit for copyright infringement and offered a chance to settle for a “significantly reduced amount,” according to a sample copy provided by the RIAA.

The RIAA asked the universities, as the Internet service providers for the IP addresses in question, to pass the letters along to the appropriate users.

“Piracy is acutely and disproportionately high on college campuses, so we have tailored our efforts to college campuses,” said RIAA Director of Communications Cara Duckworth.

The strategy involves sending monthly “waves” of letters to alleged infringers at colleges across the nation, Duckworth said. In the second wave of 405 settlement letters nationwide on March 21, the UW System received 66 letters.

Although Duckworth said the majority of universities passed the letters along, UW initially refused to do so.

In response to UW’s unwillingness to deliver the letters, the RIAA filed placeholder “John Doe” lawsuits against the users involved and subpoenaed the university in May to give up their names.

Although the RIAA filed a named lawsuit against one UW student Sept. 4, all of the students eventually settled out of court.

The incident, however, raised questions over the RIAA’s methods of preventing piracy, as well as the university’s dealings with students like Elizabeth. At the core of the debate is the controversy of filesharing in the post-Napster world.

An ”’intimidation campaign''’?

The RIAA’s recent tactics of pursuing lawsuits against students drew fire from UW’s Division of Information Technology, which says it will continue to resist the group’s efforts.

“The RIAA wanted to bypass the subpoena process and have the universities act as its agents without giving the students the other information they needed to know,” said Ken Frazier, the interim CIO of DoIT at the time of the first wave of letters.

UW behaved within its legal rights in a manner similar to other Internet service providers in refusing to pass them along, he said.

Frazier called the RIAA’s campus initiative an “intimidation campaign” and criticized the organization’s settlement scheme, which offers an initial settlement at $3,000 for a presumed offense, then increases the amount the longer an individual waits.

“The RIAA campaign traps people into making the difficult decision of how much time and money they’re willing to spend defending themselves,” he said.

Duckworth declined to comment on the exact values, saying the settlements are done on a case-by-case basis but confirmed the amount increases over time.

UW assistant law professor Anuj Desai, who studies copyright law and has provided legal advice to UW students involved in the suits, said the RIAA settlement letters are most likely designed to resolve cases before they go to trial, at the least risk to the group.

The price of settlement is small compared to possible losses in court. Copyright law allows awards of $750 to $30,000 per work, according to Desai.

Frazier and Desai also noted the RIAA cannot initially prove users actually downloaded illicit files, only that they had media files available for distribution on a peer-to-peer network.

“The IP address model is so shaky with respect to identifying downloaders,” Frazier said. “They’re not observing uploading or downloading directly.”

RIAA investigators sign on to peer-to-peer networks like any other user, then search for music files others are sharing, Duckworth said. The RIAA cites an IP address and a sample of the files it had available for download in the settlement letter, which she said is issued for “clear evidence of infringement.”

“We are not interested in pursuing action against innocent individuals,” she said.

The RIAA’s litigation efforts are meant to raise awareness about the damage illegal filesharing causes the record industry and promote legal alternatives, according to Duckworth. The money won from the suits goes to RIAA-sponsored anti-piracy programs, she said.

“The amount we settle for is a mere pittance compared to the damage done to the industry,” she said.

Elizabeth’s story

A $4,000 settlement was no pittance for Elizabeth, however, who is still paying off the loan her parents gave her to pay the money.

“It’s a reminder of how much money I don’t have … I can’t spend money as freely, which is a weird feeling,” she said.

Elizabeth first learned she was the target of an RIAA lawsuit the day she was leaving campus for Spring Break. She had seen news articles about lawsuits against students, so she was immediately wary of an e-mail from Frazier asking she give him a call.

She wasn’t prepared, however, for the stress that would accompany the legal wrangling of the next few months.

Before the subpoena was filed, university officials held a meeting for the 16 students facing suits to explain the nature of the letters and what the expected subpoena process would entail, Frazier said. They offered to show the students the letters, but advised them not to settle right away, according to some attendees.

“What Ken Frazier basically said was, ‘The situation is ambiguous and you really shouldn’t do anything until it clarifies itself,'” said UW law professor Walter Dickey, who was asked by Frazier to come to the meeting.

“They did a really good job to make it seem like it was going to be fine if I just waited,” Elizabeth said.

But the initial inaction cost her an extra $1,000 when she did settle, she said.

After the meeting, she took advantage of the options given to the students, including further meetings with faculty and free legal representation through the Economic Justice Institute, a UW Law School affiliate serving low-income and under-represented clients.

Her lawyers told her the RIAA’s threat was a “scare tactic” and that she could settle any time, Elizabeth said. According to her account, she was skeptical but didn’t have anyone else to ask.

Dickey, who met with Elizabeth early in the process, agreed she was “strongly inclined to settle.”

Her concerns over the money involved eventually combined with stress over classes to prompt Elizabeth to make a decision just before final exams.

She had recently switched her academic focus and needed to do well on her final exams, but the lawsuit weighed heavily on her mind.

“There’s a mental angle,” she said. “You’re studying or something, and it pops into your head.”

She told her lawyer she wanted to resolve the issue out of court: “He finally let me settle,” she said.

“I felt like the university was trying to fight with the RIAA, and I was what they used to fight them,” she added.

Frazier regretted the extra cost to Elizabeth but said the university had no way of knowing how the timeline of increasing settlements would work at first.

“Later we came to understand that the RIAA took the position, ‘If you don’t cooperate with us, we will not be as easy to settle with,'” he said.

University officials weren’t sure how serious the RIAA’s threat of prosecution was, according to Dickey.

Frazier said the university acted to protect students’ rights and privacy, and noted university officials faced a dilemma in their treatment of the RIAA suits.

“Do we pass along the letter and thereby lend credibility to what the letter says?” he asked. “If we don’t, are we denying the student information about the risks and liability they face?”

Elizabeth said she was grateful for the UW’s legal help but wished they would have done more research.

The campus crisis

The university is currently notifying students about the current crop of RIAA letters but won’t pass them along unless a student requests it.

Other universities have responded differently than UW to calls for cooperation with the RIAA to combat downloading.

Syracuse University, which maintains an anti-piracy outreach program similar to the UW’s, will be passing along the 50 settlement letters it just received to give students a “heads up with the legal action,” according to Director of News and Information Ed Blaguszewski.

Arizona State delivered its 23 settlement letters last March, but “gave students the opportunity to suppress the subpoenas on privacy grounds,” according to spokesperson Sarah Auffret.

The settlement letters were not UW’s first dealings with trade groups like the RIAA. Since 1999, the university has received more than 2,000 cease-and-desist notices from the RIAA, TV channels and the Motion Picture Association of America. The notices seek to stop an IP address that has allegedly downloaded copyrighted material and ask that the content be removed.

No further action is usually taken, DoIT officials said. One UW sophomore, who also wished to remain anonymous to avoid possible retribution, said the university forwarded him an e-mail from NBC requesting he delete an episode of “The Office” and the filesharing program Limewire. He took the files off the computer and sent a reply to the e-mail address NBC provided but didn’t hear anything else.

Although the RIAA continues to send such notices, Duckworth said its focus has now shifted to lawsuits. The group has filed more than 26,000 legal actions since the fall of 2003, she said, none going to trial until a lawsuit this week in Duluth, Minn.

Duckworth said it’s important for universities to take responsibility for illegal downloading on their networks, since college students are responsible for a large part of the problem.

A U.S. House of Representatives subcommittee on intellectual property echoed this argument in a May 1 letter to Chancellor John Wiley, which said UW was one of 10 schools that had received the highest number of copyright infringement notices from the RIAA or MPAA. The letter asked the university to fill out a survey on its methods to control illegal downloading.

Frazier, who responded to the survey questions, said the committee’s concerns were based on heavily biased data and likened the committee’s letter to a “communication on energy written by Enron.”

He called pinning the downloading problem on college students “ridiculous.”

“Downloading is a nearly universal activity of people under a certain age,” he said. “The communication we got from members of Congress sounded like it was dictated by the RIAA.”

A spokesperson for the committee’s chairman, Rep. Howard Berman, D-Calif., declined to comment on UW’s response pending analysis of the survey, but noted “Mr. Berman believes universities have an obligation to teach their students to obey the law.”

Why me?

Due to the bad timing typical of her ordeal, Elizabeth had to wake up at 4 a.m. the day after she received her settlement papers in June to pay the fee before she left on a family vacation.

It was an anticlimactic resolution: “It felt like I was just paying a school bill or clothing bill or something,” she said.

Her lawyers made sure the settlement agreement included all infringement through July, although the document didn’t actually admit she was guilty of anything, she said.

Once her settlement went through, she was finally able to tell friends and relatives about her experience (her lawyers had advised her not to speak to anyone about the suit beforehand).

But her relief still left feelings of frustration at what she described as the “‘Why me?’ situation” of being singled out among all the students who had downloaded music in her dorm.

“Life’s not fair, but that’s really not fair,” she said.

She said the RIAA’s tactics of “targeting people they know can’t pay” will recoup money in the short run, but won’t alleviate copyright infringement in the long run.

But Elizabeth would rather wash her hands of the whole thing.

“I don’t want to be the person who says, ‘Don’t download,'” she said. “I don’t want to be the spokesperson because I got caught…”

Then she remembered the terms of her settlement: “Or supposedly got caught.”

View the follow-up blog post at The City Within