Confronting our past is never easy. Whether you’re looking back at a failed relationship or the Bay of Pigs invasion, there are always going to be parts we’d rather … gloss over. Maybe you should have communicated better, or practiced active listening — maybe you should have considered including air support.

The point is, looking back critically is hard. There’s a reason we don’t do it that often. For much of American history, reflection is more than uncomfortable — it’s a guilt-inducing review of our screw-ups, contextualized by all the pesky, modern-day problems they caused.

As many budding internet historians have pointed out, slavery has, in fact, been abolished. Segregation and Jim Crow happened decades ago. The era in which we bound people in chains and beat them for no other reason than the color of their skin was, incidentally, not this one.

But modern times didn’t emerge in a vacuum. The legacies of our past are still intertwined in society, whether they are written quietly in the redlined neighborhoods of Milwaukee, or in the names of men that adorn our statues, university halls and monuments.

When these legacies are questioned, often by those most harmed by them, white students and administrators across the country have a poor track record in responding appropriately. Microaggressions are dismissed as “PC culture,” depictions of lynchings and blackface are labeled as “free speech,” only to be walked back, painfully slow, upon public outcry.

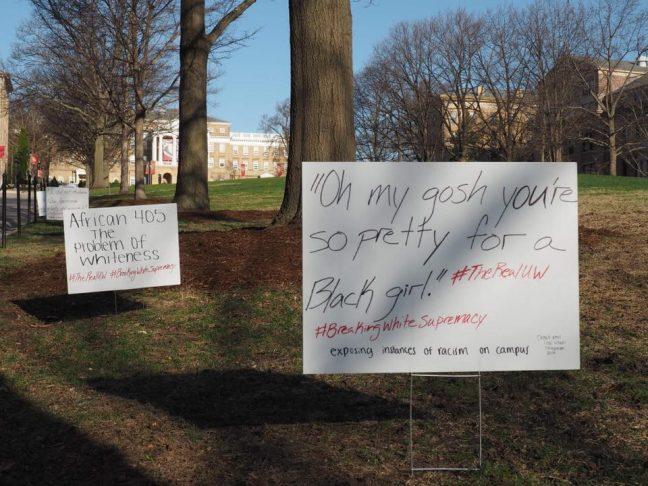

The #RealUW movement in 2016 marked one of the first public declarations of the University of Wisconsin’s failure to acknowledge the struggles black and other minority students face on campus. A line of clothing was released by student Eneale Pickett, decrying police brutality. In 2017 “The Problem of Whiteness” debuted as an African Cultural Studies course, aiming to address constructions of whiteness and their contributions to white supremacy.

All of the initiatives drew outrage from state legislators, conservative media, students and alumni. State senators considered pulling funding, alumni threatened not to send their children to UW system schools. Others, like Gov. Scott Walker, rolled their eyes and went on with life.

Monday morning, members of African Studies 405 set up a visual display on Bascom Hill. A series of signs recounted quotes from classmates, ranging from “why does everything have to be about race?” to “you’re so pretty for a black girl!” to “slavery was a few hundred years ago, they need to get over it.”

The signs led to an intense conversation, with many students protesting the singling out of whiteness for blame. For the duration of Monday, the signs remained visible — some passerby stopped to take pictures, while others frowned or even scoffed at the quotes.

Faced with varying levels of complicity in instances of oppression, white students continue to punt. We minimize injustice on campus — sometimes we pretend it doesn’t exist at all. Sometimes we lash out at the very people asking us for help.

But visual displays like the one on Bascom aren’t meant to “punish” white people. They’re meant to highlight privilege and instances of microaggression. They’re meant to spark conversation about how we engage with students on campus, and what is actually appropriate — however well-intentioned — to say to each other.

When a student indicates their experience of campus suffers from microaggressions and discrimination, we should be listening to them, not minimizing their accounts or scoffing at things which make you uncomfortable — or worse, part of the problem. If you’re doing something — intentionally or not — that is hurting another human being, wouldn’t you want to take steps to fix it?

This isn’t a “punishment” for being white. It’s not reverse racism. It’s called being a decent human being. It’s being aware of the history that still casts a shadow over how we live our lives, whether we acknowledge it or not.

The guilt and anger white people feel looking back at slavery and the Civil Rights movement has nothing on the daily experiences of people of color and other marginalized groups. They could never even begin to equate.

Julia Brunson (julia.r.brunson@gmail.com) is a sophomore majoring in history.