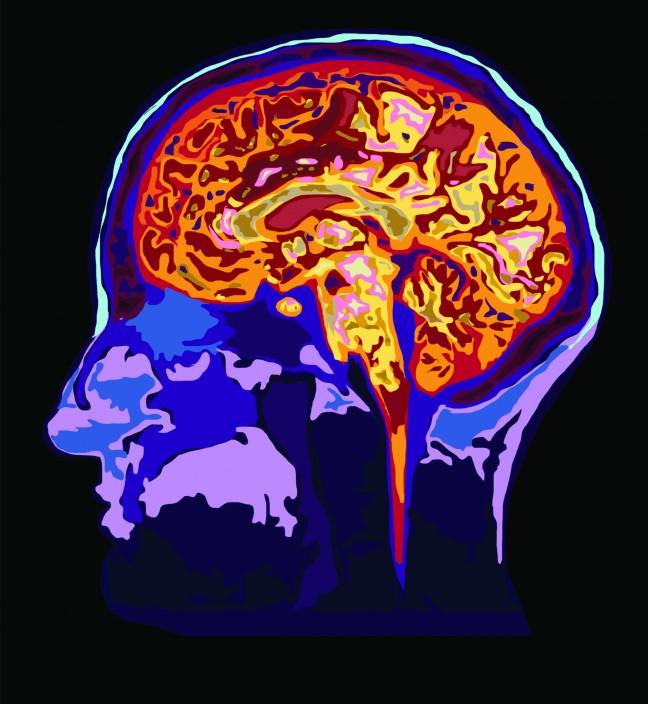

For 45 minutes, an infant is swaddled and snoozed into a cozy fMRI machine.

That’s all it takes for researchers at the Center for Investigating Healthy Minds to observe how structures inside the child’s brain communicate with each other.

Nicole Schmidt, a research program manager at the Waisman Center, is among the researchers behind the Baby Brain and Behavior Project.

“It’s so neat because the babies are just such quiet little bundles, but there’s so much going on developmentally,” Schmidt said.

Funded by the National Institutes of Health, Schmidt’s project investigates the effects of anxiety on early brain development. The project hopes to clear up how different experiences might affect a child at a cellular level and how stress shows up in people’s biology.

From one month and onward, researchers study the babies’ brains at different stages for developmental changes. At six months, Schmidt said the focus of the study is entirely on behavioral development and emotional style.

One way in which Schmidt studies this Temperament Assessment Battery is to study the child’s responses to everyday experiences.

Schmidt places the child in a chair and examines the babies’ response to a stranger in their environment.

“We measure the duration and peak intensities of different emotions during the experience,” Schmidt said. “Fear, anger, attention, activity level.”

The first babies will be turning one year old later this fall, Schmidt said.

The researchers use umbilical cords to gather genetic information from the baby, which avoids having to get more invasive blood tests from the mother or child.

“We’re over the idea that DNA is the only factor that goes into well-being,” Schmidt said. “The question is, ‘How can you uncover the role of experience?’ As a mother myself there’s just that enormous curiosity when you’re looking at a newborn child to really be able to understand their development.”

Schmidt’s project is still in its infancy, with funding from NIH for five years.

A challenge from the Dalai Lama

Marianne Spoon, a spokesperson for the Center for Investigating Healthy Minds, said the project reflects the Center’s methods for studying mental well-being.

The Center began when its founder, Richard Davidson, met with the Dalai Lama and was challenged to further scientific research in positive emotions and mental well-being, as opposed to negative emotions that result from conditions such as anxiety or depression.

“He wanted to look at exactly what areas were active in the brain when we felt happiness or sadness or anger or fear or even bliss,” Spoon said.

Davidson’s research coincided with the idea that the brain is plastic, Spoon said. Different neurons and circuits in the brain that are active during certain behaviors, thoughts or emotions form pathways that become ingrained when people use them.

But Spoon said what research has found is that there are new pathways that can be built, and so the brain is malleable.

“This isn’t to say with individuals who have clinical or mental health disorders that this isn’t a challenge, but overall we are finding that the brain is plastic, and this is very exciting news,” Spoon said.

When Davidson set out to discover the brain activity of individuals who had consistently high levels of well-being, he studied Buddhist monks for their practice in intentionally cultivating healthy qualities of mind.

“They meditate but also practice compassion and gratitude toward each other,” Spoon said. “Rather than just internally, a lot of it plays externally in their behaviors to other people.”

Davidson’s research took a focus on long-term meditators, people who intensely meditate in isolation for many hours over many years.

When looking at the differences in brain activity between novice meditators and long-term meditators, studies found long-term meditators were able to rebound from stress more easily.

“Richie has really been a pioneer in this area in looking at the science of well-being, the science of mindfulness, how to learn about positive qualities in such a way where we can unearth whether they can be learned or taught,” Spoon said.

In his research, Davidson has outlined four key constituents of well-being: the ability to sustain positive emotion, response to negative emotion, mindfulness vs. mind wandering and pro-social behaviors, or the ability to empathize.

But for some with depression, the ability to shake the feeling after a negative experience is lessened, along with the ability to sustain positivity, Davidson outlined in the World Happiness Report.

Turning research into practice

Robin Goldman, one of the co-science directors at the Center, said many of the research projects, including Schmidt’s Baby Brain and Behavior Project, work to look at development of mental well-being in different age groups.

“Looking at different curriculum in school, at meditation practices in the workplace, we can teach short-term and lifetime well-being practices,” Goldman said.

For those who don’t want to take up the meditation lifestyle of a monk, the Center teaches several techniques to reach mental well-being.

The Center has developed the “Kindness curriculum,” which promotes social and emotional skills among four and five-year-old students.

These children are taught emotional self-regulation and the development of impulse control and kindness.

Practices such as sticker sharing, breathing techniques and compassion for the sound of a siren are taught to the children to promote positive well-being.

The Center also has online audio compassion training techniques on its website to further promote the well-being practices which involve external, pro-social behaviors.

“[Davidson] is very passionate about getting the work out there and making sure it can actually promote well-being and reduce suffering in the world,” Spoon said.