A few months ago, the U.S. Supreme Court vacated Gill v. Whitford, a case originating in Wisconsin that fought to end partisan gerrymandering, and remanded it to the District Court due to lack of Article III standing — that is, the plaintiff must sufficiently demonstrate individual harm. It was recently announced the case will likely be heard some time in April 2019 by a panel of three federal judges.

Underlying this case is an important debate about the controversial practice, which often intentionally creates voting districts to put opponents at a disadvantage. Wisconsinites are increasingly working to eliminate all partisan bias in this process. In his “Government for Us” agenda, released at the beginning of this month, Democratic gubernatorial candidate Tony Evers said he supports the creation of a nonpartisan redistricting commission to re-draw the district lines following the 2020 census.

Anti-gerrymandering activists, like Andrea Kaminski, a former executive director of the League of Women Voters, believe “Having the ability, the freedom, to elect your representatives in a fair contest shouldn’t be a partisan issue,” and are seeking an independent redistricting system, similar to Iowa’s, that does not take into account partisan interests such as voting statistics or the homes of the incumbents.

It seems obvious getting rid of partisan gerrymandering will both protect the integrity of Wisconsin voting and is in both party’s interests to do so. But a closer look at the reasons for gerrymandering will reveal, the practice is easier to criticize than provide an alternative solution for.

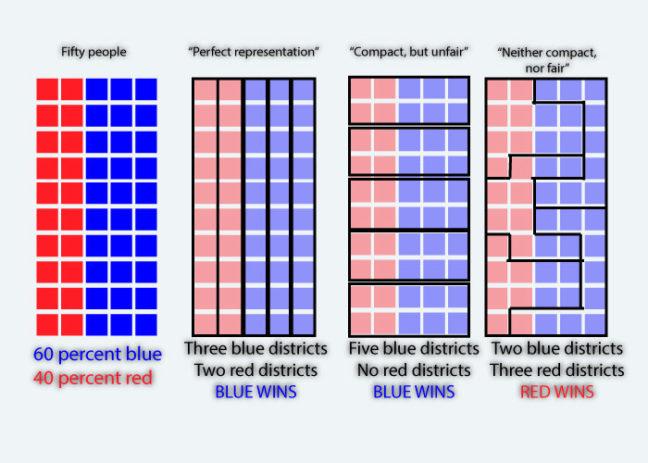

The controversial aspect of partisan gerrymandering is not the act of gerrymandering itself — rather, it is the intentional practice of skewing the state’s party representation out of proportion. The majority party has the opportunity to “crack” or “pack” the districts. Cracking refers to splitting up the opposing party into several districts to dilute their voting power, while packing refers to grouping them into one or two highly concentrated districts to limit the number of seats they will win in.

Point Counterpoint: Gerrymandering may seem to be poor system, but it’s the best we’ve seen

One way to measure the impact of these processes, cited in the court case, is the Efficiency Gap. Because one only needs 50 percent plus one to win a seat, a lot of votes both for and against the winner are considered “wasted.” If both parties waste the same number of votes, then the efficiency gap is zero. The problem, as discussed by one of the creators of the EG formula, is that it is only a measure. It is not a legal test which incorporates all the values and principles people care about, of a gerrymandered district. The proposed EG measurement of 7-to-10 percent efficiency is a necessary, but insufficient condition of a partisan gerrymandered district. Some districts, like Madison’s, will always look inefficient because of the high density of Democratic voters in this area.

Furthermore, gerrymandering is often used for acceptable reasons, such as, ironically, attempting to make partisan representation more proportional. Voters, unbeknownst to the larger picture, freely do this to themselves. Because Democrats tend to live in urban, small geographical areas, while Republicans are more spread out in the large, rural areas, gerrymandering is the only way to balance the disadvantage Democrats have in terms of how many districts they occupy.

For Congressional districts, all states must abide by two rules when drawing these districts. Equal population as mandated by Wesberry v. Sanders and under the Voting Rights Act of 1965, must not discriminate against minority races or ethnicities. Article 4, Section 4 of the Wisconsin Constitution states the 99 members of the Assembly are chosen from single districts that must “consist of contiguous territory and be in as compact form as practicable.” If these rules seem fair, gerrymandering is a useful and unavoidable process.

To clarify, the plaintiffs were not able to receive Article III standing because while they were able to demonstrate that a gerrymander injured the collective interest of the Wisconsin Democrats, they could not demonstrate that it had an ill effect on their individual and legal right to vote. This is important to note because while partisan gerrymandering is upsetting and has the power to discourage people from voting, it does not detract from a citizen’s legal right to vote nor the equal access to a representative concerned with local issues. While many people feel discouraged from voting, this is not quite the same as being disenfranchised from voting.

Gerrymandering gives way to lack of bipartisan legislation, Whitford says

While a nonpartisan redistricting committee is a plausible and not completely repulsive idea for revising district lines, it is not clear the problem stems from politicians intentionally making the other party worse off. Geographical factors and people’s free choices are what make the redistricting process very complicated. The people whom individuals choose to live around will play a role in the strength of their individual votes.

Lianna Schwalenberg (lschwalenber@wisc.edu) is a fifth-year senior majoring in communication arts and philosophy.