I’m of the opinion that cancer patients have cancer solely to get attention and be dramatic. That girl with sickle-cell anemia — she should just think happy thoughts to get better. It’s her fault if that doesn’t work. Why does that man have a brain tumor? He’s had such a satisfactory and happy life, he just got a promotion and his family is loving and healthy.

The above assertions shouldn’t make much sense to a rational individual. They should even be viewed as inflammatory or ignorant. It is generally accepted someone with cancer or sickle-cell anemia doesn’t get blamed for their condition. Their sickness is not illegitimate, not their fault and definitely not something to be ashamed of. Why, then, doesn’t society apply this moral, seemingly innate logic to diseases of the mind? They are equally real and valid ailments, are rooted largely in biology and can be every bit as detrimental as, say, heart disease or cancer.

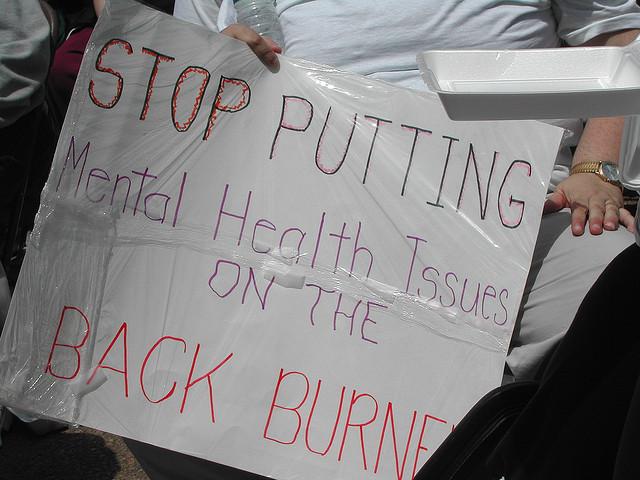

It’s time we have an honest conversation about how we view mental health in this country. Frankly, many don’t care about mental illness. People don’t understand it because they can’t see it. It makes them uncomfortable, so they ignore the issue. Unfortunately, people are embarrassed to say they have ADHD, anxiety, depression, etc. It’s time we talk about how to change our societal attitude toward mental illness from a stance of repression and disgrace to one of open acceptance and progress.

The University of Wisconsin chapter of the student organization National Alliance on Mental Illness often employs the catchphrase “Stomp Stigma” — and for good reason.

The societal stigmatization of mental illness is, to varying degrees, mirrored on our campus. Unfortunately, mental illness is much more common in the United States than most realize. While one in four people will develop or exhibit a clinically diagnosable mental illness in their lifetime, two out of three with a mental illness will not seek treatment. Fear of judgment, fear of societal rejection and lack of information about mental illness often stops people from getting help; stigma cripples opportunities for healing.

This stigma, one of America’s major sources of discrimination, is NAMI-UW’s main target. UW students need to know it is not uncommon to feel depressed or anxious, as high school and college-age students are among the most susceptible to these particular mental illnesses.

Other diseases of the mind are less common, but still just as delegitimized by society. People with bipolar disorder are called crazy or psychotic, those with OCD are dubbed neat freaks and those with other brain disorders are given other humiliating distinctions that further ostracize their illness.

We, as an organization, recognize this fact and provide peers with a safe and comfortable outlet to talk about these issues. But it shouldn’t just happen within our club’s borders. It should be the role of the entire student body to listen to and support one another, not shame, discredit or ignore those struggling with mental illness.

Struggles with mental health have, in some way or another, affected everyone. The effects are just as tragic and hard to fight as other diseases, but something about the disease being concealed in the mind makes it hard for us to understand it and to be sympathetic toward it. This trend and inclination toward making mental illness taboo can end, though, by spreading the “Stomp Stigma” message.

If you’re reading this and struggling with mental illness, please do not be afraid to reach out and get help. You are not alone and you will not be humiliated or ignored. I challenge UW’s student body to stop the stigmatization of mental illness and to step forward with empathy, openness to difference and progress as our common goal. Our campus, our lives and our societal future could be so much more inclusive and compassionate if everyone did so.

Conlin Bass (cbass2@wisc.edu) is NAMI-UW’s marketing director and is a freshman majoring in neurobiology.