University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health associate professor Whitney Robinson spoke at the University of Wisconsin’s Department of Population Health Sciences seminar Monday about principles that have guided her work in the past year regarding racial disparities and the pandemic.

Robinson said her research uses a diverse toolbox of data study designs and methods and mostly focuses on social determinants of health. With this design, she tries to let the problem guide her study, and within the past year, the public health emergency of the U.S. COVID-19 outbreak has felt the most urgent.

“I’m not an infectious disease epidemiologist, I’m not a modeler, I don’t have a lot of experience in applied epidemiology and community work, but I did feel called to try to contribute what I do have to bring,” Robinson said at the seminar.

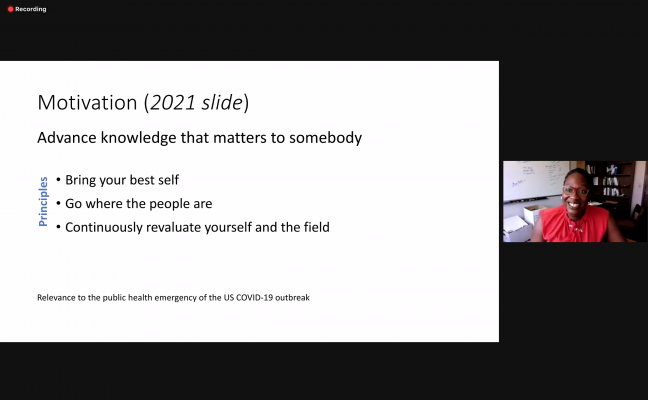

Robinson said three principles helped guide where to spend her efforts — bring your best self, go where the people are, and continuously reevaluate yourself and the field.

To bring her best self, Robinson said she wanted to add value by applying fundamental epidemiological principles to understand causes of health differences across diverse socio-demographic groups.

For example, early studies showed COVID-19 was only common in the elderly, but those studies were based on an unrepresentative hospitalized population, Robinson said.

“I felt like from pretty early on, from seeing studies in other countries, that there was a large reservoir of young people who had SARS-CoV-2 infection,” Robinson said. “They were subclinical because they weren’t sick enough to use precious hospital space, but they are really important for understanding transmission dynamics because they’re part of communities, and they can be people who are transmitting.”

Robinson became involved in a collaborative study inspired by a strategy used for surveillance in the HIV epidemic in Sub-Saharan Africa. Robinson said they used leftover blood serum from antenatal care to measure HIV prevalence and to monitor transmission through that population.

Robinson said her study used leftover blood from prenatal labs and represented more racial and ethnic diversity than studies that rely on recruiting people. The study found a 10% overall prevalence of COVID-19 antibodies but the findings included huge racial-ethnic disparities.

For example, Robinson said the Hispanic Latino population was closer to 30%, and the Black population showed a higher trend of COVID-19 positivity than the white population.

“I think so often in the U.S., we think about ourselves as being very advanced, but I think that the COVID-19 experience has been really humbling,” Robinson said. “There are many countries that have much less wealth than we do who have done amazing because they have relied on strong public health principles.”

Robinson said she has been featured in a print newsletter put out by a nonprofit called The Marian Cheek Jackson Center as part of her effort to “go where the people are.” Robinson said the publication has helped more people read her public health articles and advice because the publication matters to the specific community.

Robinson also said she has been active on Twitter to reach people that she cares about and draw journalists’ attention to important issues.

“I feel called to put my voice out there because I think there has been a dearth of voices who think about health inequalities from the perspective of Black Americans,” Robinson said. “I just realized early on that some of the things that seemed very obvious to me didn’t seem obvious to other people and that it was a responsibility for me to try to publicize things that I think are important.”

One way Robinson has reevaluated the field of epidemiology is by collaborating on a paper about how some of the emphasis of epidemiology on individual-level risk factors for poor outcomes facilitate structural racism and limit accountability for structural causes of ill health.

Robinson said researchers need to take a step back and think about larger transmission dynamics and burdens. The individual-level approach situates the cause of poor health in a person rather than considering all the forces that lead to poor health, Robinson said.

“I’m really just reflecting on my long-held values about wanting to do work that matters to somebody and thinking about how I’ve prioritized my time over the past year, trying to think where can I add value,” Robinson said.