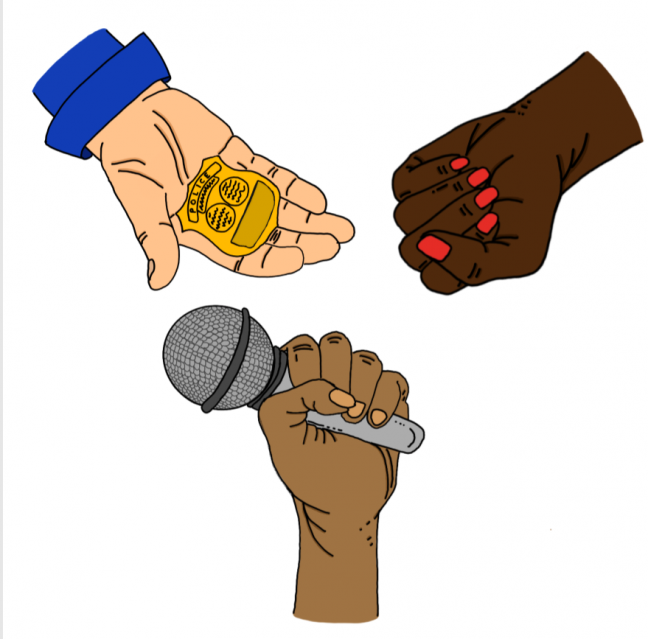

At 5:09 a.m. May 29, CNN correspondent Omar Jimenez was reporting on-the-ground at the protest in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The protest, one of many across the United States supporting the Black Lives Matter movement in the wake of the death of George Floyd, started peacefully but ended in a different state.

According to CNN, Jimenez, who identifies as Black and Latino, was reporting on an arrest happening near a city police department precinct that protesters had burned and officers had abandoned. Jimenez and his crew stood in front of a line of police officers in riot gear, and officers approached them shortly after they started reporting.

When the officers asked him to move, Jimenez identified himself with his CNN identification card. His crew filmed him telling the officers, “We can move back to where you’d like here. We are live on the air at the moment.”

The officers then proceeded to arrest Jimenez, his crew and his producer, with the camera rolling until it was seized.

Jimenez’s arrest made headlines, noting many white coworkers at the protest were left alone. The governor of the state issued an apology to the president of CNN less than two hours after the arrest was made, and Jimenez and his crew were released later that morning.

His arrest wasn’t the only press-related issue to make the news, however. Across the nation, from Minneapolis to Louisville to New York City, reports of police harming members of the media reporting on the protests made waves.

Reporters have flocked en masse to social media, decrying the acts as violations of the First Amendment. And as reporters question whether their rights will be violated in the future, incidents coming to light mean the answer is elusive at best.

(Press)ure in Madison

Madison has been rife with protests for days now, and local journalists have been discussing and covering the issues at hand.

Jason Joyce is the City News Editor at the Cap Times and has worked for Isthmus for 15 years. He graduated from the University of Wisconsin in 1992.

Joyce discussed his experience watching reporters’ treatment during the protests.

“When [Jimenez] was arrested last week, I thought at first it was a case of racial profiling,” Joyce said. “But after seeing other journalists arrested, assaulted and basically bullied by police — and not just in Minneapolis — I’m starting to wonder if it’s part of a strategy to keep the public from knowing about police tactics.”

Joyce said in Madison, the police department typically cooperates with media outlets. So when, on May 31, Joyce realized protesters were going to stay out past the city-imposed 9:30PM curfew, reporters began wondering if they would be arrested.

Joyce said he texted Joel DeSpain, the Madison Police Department’s spokesman, and was told the city attorney said press were exempt from the order.

“Having said that, I’ve seen video indicating some reporters have had tear gas fired directly at them, but there are a lot of agencies working these protests and I’m not sure the circumstances,” Joyce said. “It’s a risk covering protests where people confront police officers, especially when they start throwing rocks and tear gas comes out.”

George Balekji, of NBC-15’s Madison arm, put video on Twitter of having a tear gas canister thrown at him while talking to a source, though he later tweeted it may have been a smoke canister based on the coloring. In the video, he says he “literally saw an officer just step and toss it.”

Balekji verified to the Herald in a statement that an “officer did throw the canister and it was smoke.” He said in the video the source he was interviewing covers the specific officer that threw it, but “an officer did throw it, I saw it.” He clarified, however, he was not sure which agency the officer was from.

DeSpain spoke with The Herald and said Channel 15 hadn’t contacted him with concerns about MPD regarding tear-gassing of the press.

“I had one person contact me about that this week after seeing a video that involved a Channel 15 reporter, and the Channel 15 reporter I believe told them that that tear gas canister was in fact thrown at them by a protestor,” DeSpain said. “In times when we use tear gas … protesters would throw [canisters] back at police usually, but in this case it sounds like they threw it at a media member.”

DeSpain said he wanted to note that in Madison, it was a very small percentage of people who were out on the streets that behaved at all violently, like throwing canisters.

He also said MPD wanted to support the media.

“We’re here to make sure that the media has complete access to what’s taking place,” DeSpain said. “Whoever’s putting out information about these events, in my opinion, is a journalist or reporter, and we’re here to support them.”

Alice Herman, a current investigative reporting fellow at In These Times and former intern at The Progressive magazine, is currently based in Madison.

She discussed her own experience at the protests.

“I was a the protest on Saturday, Sunday and Monday in a press capacity. I was not obviously distinguishable from the rest of the crowd, and was subject to tear gas on multiple occasions and police projectiles on one,” Herman said.

She added she was prepared for arrest at the protest, with bail and legal contacts written down just in case.

DeSpain said tear gas has the potential to affect people in its vicinity — some who aren’t being directly targeted — at which he expressed his sympathy.

“There are people in the area who are inadvertently impacted by tear gas. And that’s very unfortunate,” DeSpain said. “I would encourage people, if you’re covering this event, move a safe distance away. And sometimes, in the volatility of the moment, it’s difficult, I get that, if there’s lots and lots of people around.”

Joyce said while reporters shouldn’t get in the way of police, the community expects them to be there.

“Reporters provide an important check on police authority simply by observing them as they work,” Joyce said. “Members of the community have told us directly that they expect us to be there to make [sure] police officers don’t step over the line and that the official account of what happens is accurate.”

DeSpain said he wanted to hear from reporters if they had issues with MPD.

“There shouldn’t be anybody from Madison Police asking you for your credentials,” DeSpain said. “You can say ‘I’m a reporter,’ and that should be good enough. And if it’s not, call me.

Legal (Press)edent

Howard Schweber, UW professor of political science and affiliate faculty member of UW’s law school, said from the founding of the United States, press freedom in the First Amendment has always been recognized and considered important. That being said, he noted it as “a large and complicated topic.”

Robert Drechsel, UW professor emeritus in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication, noted what the press clause meant for limiting government power.

“In a nutshell, the First Amendment’s press clause places a substantial, though not absolute, limit on the power of government to regulate, restrain or punish the media, particularly if the government is attempting to do so because it objects to the content or viewpoint of what the media publish,” Dreschel said.

Despite this, he said coming after the media for what they publish “is possible, but still not easy,” and courts have generally allowed for some power in the government to regulate the actual process of newsgathering.

Schweber elaborated on government involvement in press and newsgathering.

“There is definitely a dominant understanding that it is improper and sometimes unconstitutional for government agents like the police to interfere with the press in the exercise of their First Amendment functions,” Schweber said. “This produces a lot of clashes, as police are understandably not always eager to have their actions chronicled. In the modern era of suspicions about ‘fake news’ and the deliberate delegitimization of the public media, those defensive tendencies are reinforced by a political narrative coming from the very top of the US government.”

Schweber said in practice, the US Supreme Court has been stingy about granting exclusive rights to the press. He noted special situations, like criminal trials, where specific press rights have been granted, but journalists have never had unlimited access to information.

He cited a 1978 case, Houchins v. KQED, where courts gave no right of access in prisons or jails to the press. Chief Justice Burger in that case wrote the Court “has never intimated a First Amendment guarantee of a right of access to all sources of information within government control.”

Dreschel agreed it wasn’t a clear-cut issue, saying “it isn’t so easy to separate the process of gathering news from publishing it.”

He discussed the detention of Jimenez and his crew, arrested on a live CNN feed.

“A good example was the detention the other day of [Jimenez and his crew] as they were doing a live broadcast during the Minneapolis rioting. The police directly interfered with the newsgathering process, and simultaneously were interfering with a live broadcast,” Dreschel said. “And the media might have a stronger claim of First Amendment violation if it could be shown that journalists doing live work were suddenly detained because the police didn’t like what was being broadcast, or were acting arbitrarily.”

Schweber added there is no press immunity from the law — if you’re committing a crime or defying a legitimate police order, there’s no legal recourse in simply being media whilst doing it.

He said, however, if police interfere with members of the press simply recording or documenting their actions, that’s unconstitutional and the city could be liable for damages.

“It’s not about a special right of the press — anyone is entitled to record public events,” Schweber said. “If it were not for individuals with cameras on their cell phones, most of the major instances of police killings in the past few years would never have come to light.”

Schweber also discussed a pair of cases decided together by the Third Circuit in 2017 — Fields v. City of Philadelphia et al and Geraci v. City of Philadelphia et al.

The opinion from those cases says to “record is to see and hear more accurately. Recordings also facilitate discussion because of the ease in which they can be widely distributed via different forms of media.”

It draws the conclusion that “recording police activity in public falls squarely within the First Amendment right of access to information. As no doubt the press has this right, so does the public.”

Schweber noted many have demonized the press as a political strategy, as other aspects of the First Amendment are now being pushed to their limits — the state Republican legislature introduced a bill in 2019 to protect free speech on University of Wisconsin campuses after reported stifling of conservative students, and the Supreme Court ruled in 2018 that a baker wasn’t required to make a cake for a gay couple.

“A particularly noteworthy element of police misconduct has been the deliberate targeting of the press to prevent the public from seeing what is happening,” Schweber said. “In an era in which First Amendment protections for corporations and religious believers are being pushed to an extreme, disregard for the equally important First Amendment value of a free press has been promoted as a deliberate political strategy. There is nothing new about clashes between reporters and police, but the environment of this past week reflects a deep hostility to First Amendment values.”

Dreschel discussed his opinion on incidents of the press at recent protests and their treatment.

“The incidents I’ve read about seem to indicate that law enforcement officers have engaged in a number of dangerous, ill-advised and counterproductive actions against a number of journalists who were doing nothing wrong,” Dreschel said.

He added that covering unrest “is inherently dangerous enough,” let alone when reporters fear harm from police.

Dreschel said, however, he appreciated seeing some recognition of the press by the government recently.

“Some authorities — Gov. Walz in Minnesota particularly comes to mind — have publicly apologized and acknowledged the important role of the press in covering the unrest. And that has been welcome and downright refreshing to see,” Dreschel said.

Campus Im(press)ions

Before her work in Madison, Herman worked in journalism as a student on the paper at Grinnell College, where she attended. And while Joyce said he’d never thought he would actually go into journalism as a career, it was actually his experience at UW that helped drive him there.

“I showed up at The Badger Herald’s organizational meeting midway through my junior year hoping to write music reviews. Editors found out I knew about state politics because I had worked as a page in the Wisconsin Assembly and started assigning me state stories,” Joyce said. “I got addicted [to] the feeling you get when writing on deadline, having important people call you back and being able to basically ask anybody anything as long as I had a notepad in my hand.”

Joyce later became Editor in Chief at the paper in 1992.

For current journalism student Lauren Lessila, a rising junior who’s reported for The Daily Cardinal, her drive to write comes from the media’s impact.

“I want to pursue journalism because news outlets are how people receive important, life-saving information that is put into the correct context,” Lessila said. “During the unprecedented pandemic and uprise of the Black Lives Matter movement, I have seen too many people with incorrect, out of context, or misinterpreted information — I feel I have a duty to change that.”

Lessila said she’s taken Journalism 563, a class about media law that helps educate UW students on their rights as press. She said she deems some actions against reporters in wake of the protests to be a violation of the First Amendment, per what she’s learned.

She noted her feelings on the subject, as well.

“Watching a reporter do their job peacefully and with the intention of exposing the truth and [being] arrested as a result makes me sick to my stomach,” Lessila said. “It only strengthens my belief that the world needs journalism, now more than ever, to uncover the truth, expose lies and give straight, unbiased facts.”

Lessila added the journalists in question “were forced to become the story” when their intentions were simply to report on the issues at hand.

Caitlin Geurts, another rising UW junior studying journalism, talked about having mixed feelings in light of the protests and press.

“I think most journalists have been treated similar to protestors. They can be confused for opportunists or rioters and treated poorly,” Geurts said. “Of course, there have been select videos of brutal removals of the press by police force, but those videos don’t include the countless journalists that have been doing their jobs among the tear gas and rocks since day one and that haven’t been brutalized.”

Geurts noted when issues involved tie to your employment and source of income, it becomes more nuanced.

“I think it’s easy to read into [everything] that’s happening, but I think it’s very important to remember that both the police and journalists are doing their jobs — whether that be good jobs or not — in this situation,” Geurts said.

Herman said she suggested students work in pairs or groups reporting for safety and support, and Joyce said students should stay educated on their rights and journalism ethics, and be prepared to sometimes have to stand up for themselves.

Joyce added, despite the concerns people have right now, some of the best parts of journalism include the on-the-ground work — and they’re often the parts that draw people into the career to begin with.

“Covering protests can be exhilarating. These kinds of stories are why a lot of us got into journalism,” Joyce said. “And the other night when protests were breaking out all over the country and I was coughing from the tear gas on the Capitol Square here in Madison, I thought I was pretty privileged to be right in the middle of a historic moment.”