University of Wisconsin Archives held an open house for their newly published teaching kit on the 1969 Black Student Strike Wednesday night.

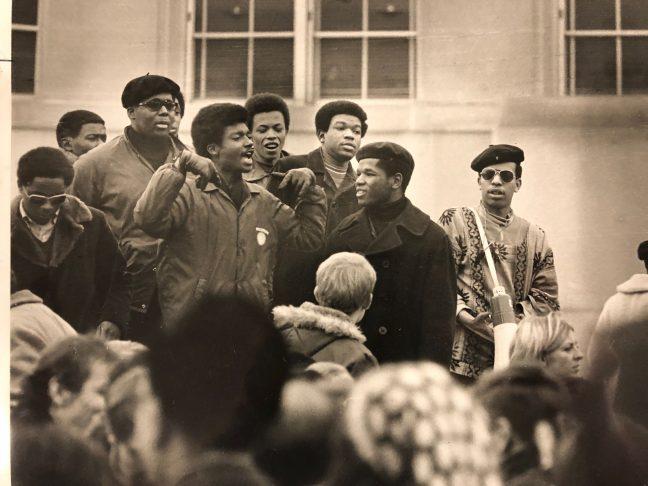

February marks the 50th anniversary of the strike, which took place at UW after black students, frustrated with UW’s race relations, wrote a list of 13 demands. Students marched and boycotted classes until their demands were met, eventually resulting in the establishment of UW’s Black Studies Department.

UW Archives worked with student historian Rena Yehuda Newman to create a teaching kit that looked at the strike and its relevance in the modern era.

“These demands were demands for greater on-campus justice in order for the black student activists to be able to thrive as students,” Newman said. “They were making demands specifically about what it meant to get a good education.”

Fifty years ago, the students presented their demands to Chancellor Hugh Edwin Young Feb. 7. Young didn’t budge.

One of the primary sources included in the teaching kit was a letter from UW student Licia Dearth to Young.

“I for one am disgusted with your naive view of the demonstrations,” Dearth wrote.

Students began marching Feb. 10. Roughly 1,500 student activists were met by 125 riot-equipped Madison police officers as they marched from Library Mall to Bascom Hill Feb. 11. By Feb. 13, Young had called in the National Guard.

While many white students marched alongside the organizers, some groups opposed to the strike, like the student group Young Americans for Freedom.

YAF published a flyer condemning the strike, claiming it was disturbing the campus.

“The student strike that we faced today represents the triumph of the totalitarian mind,” YAF wrote. “Its leaders, black and white alike, are the methodological heirs of Adolf Hitler.”

The open house kicks off several events that will be commemorating the strike, as well as a collection of interviews with some of the protestors.

These interviews were conducted by student journalists in collaboration with the Black Cultural Center and the Black Voice.

“Having the opportunity to look back into this legacy of student activism that I’ve inherited as a student has been powerful for me,” Newman said. “To know that we actually inherit a very rich legacy of lessons and ideas from people who have done this work before.”

Many of the 13 demands are still unmet, Newman noted, saying that UW’s response to the strike is part of a “legacy of state violence” that students need to acknowledge.

Newman stressed the powerful impact of the strike and how it has shaped UW and its students. History is how we remember the facts but memory is who we are because it happened, they said.

“What does it mean that the administration of my school 50 years ago on this month called in the National Guard on student protesters?” Newman said. “What does it mean for us to collectively inherit the legacies of racism at UW and work through that as a community?”

The teaching kit is being developed into a syllabus in an effort to continue discussions of the strike and educate current students. Newman is also working to document the work being done by current UW activists so that their stories can be studied in 50 years.

Newman ended the open house by explaining that the importance of the archives is to can give context to UW’s history and highlight communities that would otherwise be forgotten.

“Memory is a way to combat erasure,” Newman said. “It’s a way to combat violence.”