Sarah Stillman, a staff writer from The New Yorker, spoke Tuesday about covering the intersection between crime and immigration during the Trump administration.

For the most part, Stillman said, the topics of crime and immigration have felt pretty separate, but recentlythere has been an increasing convergence.

She brought up a number of ways she’s seen this convergence emerge through the reporting she’s done.

One of the ways was exploring the forgotten toll of border militarization. She said the massive number of funds sent to secure the border yielded a greater policy implication and an incentive for drug cartels to help the human smuggling business. With greater militarization, the rates people are willing to pay to get across have “massively escalated.”

“People haven’t stopped crossing [the border] — they have just started taking much more circuitous routes,” Stillman said. “We’ve also seen a massive surge in the number of people who are dying as they try to cross the border, whether they’re dying of starvation, dehydration or cartel violence.”

In addition, there are also a large amount of kidnappings that happen when people attempt to cross the border, Stillman said.

Initially, Stillman thought this was an issue predominately in Mexico. When she heard about what happened to the Godoy boys, however, she realized this was also an American issue — the boys were kidnapped on the U.S. side of the border in Texas.

Stillman wrote an article about the Godoy family, detailing their struggle, experience and reunion. While speaking with the family, Stillman realized the relationship between local law enforcement and federal immigration enforcement can be jeopardizing to undocumented individuals when a crime has occurred.

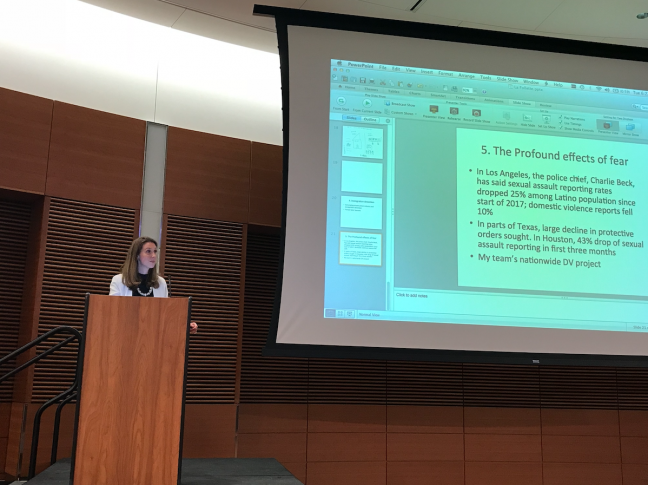

“The massive number of undocumented people who feel they have no path to legalization … can often be very anxious about calling law enforcement,” Stillman said.

Stillman also spoke about her work with students at Columbia University’s journalism school. Stillman and her students created the “Trump Tracker,” which was a way to monitor information about immigration enforcement at the state and local levels and compare it to Trump’s rhetoric about deportation.

While investigating, Stillman wondered if Trump’s rhetoric about deporting individuals with serious felonies would match policy. She quickly found out that it did not. She found that a number of cases didn’t “fit the mold,” and instead of serious felons being deported, it was mothers or teenagers.

“Low level offenses, like traffic violations, can now be a matter of life or death,” Stillman said.

In light of all this, Stillman said the most hopeful thing she’s seen in the last couple of months has been people who have the most to lose step forward and share their voices. She said these stories are especially relevant with the debate on Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, and how DACA is being used as a “tool.”

In a similar vein, Stillman said social media is a tool that is influencing the conversation and forcing mainstream journalists to have conversations they don’t want to have.

“Social media is shaping the conversation, and it’s not just us high horse journalists telling other people what to care about,” Stillman said. “[It’s] actually people who are living these experiences. People are videoing ICE when they showed up in the courthouse in Denver intimidating human trafficking victims and making them feel like they can’t come forward, and people are uploading videos of ICE raids.”