Football Saturdays, pink flamingos and sitting with Abe on Bascom go back years of University of Wisconsin tradition, but the campus was built on land where traditions had already existed for generations.

Ho-Chunk, or “people of the big voice” were the original residents of the Great Lakes region. Ho-Chunks have occupied Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois, Nebraska, South Dakota and Minnesota, and many still reside in Wisconsin today, according to the Ho-Chunk Nation website.

The Ho-Chunk culture, while in better protection today, has been seriously threatened in the past and still has an endangered language today, although efforts to keep it alive continue through youth education. At UW, the language is still taught by an elder, but not for credit.

Aaron Bird Bear, American Indian Curriculum Services consultant, said the Ho-Chunk Nation and its relationship with the university is one of complex conflicts, understandings and reconciliations. For more than 150 years, the campus was built and expanded on Ho-Chunk lands. Today, the university has a major role in leading Native American studies.

Director of the American Indian Studies Program Rand Valentine said in the 20 years he has been here, he has witnessed the program grow significantly from just a few people. He said when he has taught the Ojibwe language, he often starts out with a class of 50 students who are highly interested in the language, some native and some not.

Still, growth for American Indian Studies, much like other ethnic studies programs, is difficult.

Bird Bear said while these programs may not see new hires soon, professors who participate in ethnic studies classes have tenure in other departments and will likely keep the programs going.

UW, as one of the only Big Ten universities with such a strong relationship to Native American cultures on campus, stands out nationwide with its American Indian Studies Department.

“Are there any reservations in Indiana? Illinois? Ohio? Pennsylvania? No,” Aaron Bird Bear said. “They completely ethnically cleansed those states of the Native American nations there. So in the Big Ten, we witness and understand that we are on the frontier of ethnic cleansing, and we kind of understand that native nations still remain in our Big Ten state.”

Today’s Battle

“We’re kind of in a period of conflict today,” Bird Bear said. “We had one of the largest protests since the Vietnam War era, Black Lives Matter. The Race to Equity Report reminds us that in southern Wisconsin, we still have a lot to work out and understand.”

According to the 2013-14 Data Digest, American Indian undergraduate enrollment in 2013 was at a total headcount of 65 students, with numbers declining over the past decade.

Valentine said he was alarmed at those numbers and speculates those decreases may be a result of the loss of past recruiters.

Janice Rice, a Ho-Chunk Nation citizen and outreach librarian at UW, said the loss of a Native American recruiter has made it extremely difficult to bring in more Ho-Chunk or other native students.

“We haven’t had a Native American recruiter for over two years,” Rice said. “Now that there is no recruiter, there is no Ho-Chunk students — there really weren’t very many to begin with.”

Rice said that because Ho-Chunk Nation pays for the education of its university students, UW admissions should not use budgetary cuts as an excuse to not have a recruiter or to have such low native enrollment rates.

“We’re here, we have the money to pay, does the institution care?” Rice said.

Wunk Sheek, one of UW’s Native American student groups, has prioritized low Native American enrollment in its mission to practice and celebrate Native cultures.

Dylan Jennings, 2013 graduate and former leader of Wunk Sheek, said the group’s goal is to create a secure community on a large campus that can often be overwhelming for Native American students who come from the tight-knit community lifestyle of their native tribes.

A major issue, Jennings said, is not just enrollment but retention of Native American students.

“I’ve had the privilege of being down there and finishing my undergrad there, but it’s a sad thing because you see a lot of our Native people, the ones who you’re close to, not make it and go through hard times and have to drop out and leave,” Jennings said. “That’s a really rough thing on our population.”

Wunk Sheek also practices efforts to reach out to the larger student community for cultural education.

However, Jennings said during his time with Wunk Sheek, the group lost its status as a registered student organization and with it went funding from Associate Students of Madison.

Jennings said the group was fortunate to still have a Native house on campus, but the ability to fund all of the group’s cultural activities has been a challenge.

“We’re a very overlooked group of people. We’re one of the biggest universities around, and some people still have the mentality that Native American people are extinct and in the past,” Jennings said. “We try to deal with these stereotypes in the best way we know how — through education — to teach them and do outreach, which all comes back to funding. How can a bunch of students organizations [do] those things without having the funding to do them?”

Relative Progress

Still, understandings of Native American cultures have come a long way in the state of Wisconsin, Bird Bear said.

Bird Bear said whereas once those of Native American heritage may have been ashamed, a more accepting society overall has made multi-ethnicity “cool.”

What was once prosecution and destruction of Native American people and sites has now become valuable to the state and is a major source of research at UW, he said. Native Americans have lost many archaeological sites over the past 150 years, but shifts in attitudes and policies keep remaining sites protected.

“We have an incredibly robust and powerful Native American nation, who have been incredibly smart and savvy the entire time,” Bird Bear said. “We are very special with that.”

Last year, Wisconsin celebrated its 25th anniversary of Wisconsin Act 31, which requires the instruction of history and culture in K-12 schools of several tribes.

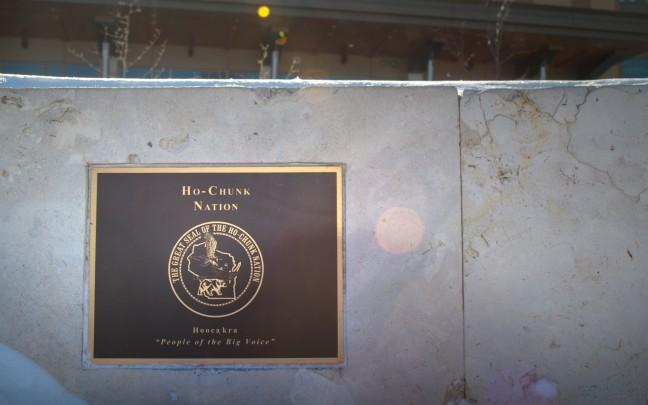

Throughout campus, tributes can be found to Ho-Chunk burial sites and living regions.

Dejope residence hall, in particular, pays tribute to the Ho-Chunk.

Located on the west side of campus, Dejope was given a name meaning “four lakes” and is the location of many archaeological sites significant to the Ho-Chunk peopl,e who have occupied the area for generations.

A fire circle facing the lake pays tribute, with bronze plaques representing different Native American Nations. The first floor is covered with symbols and artwork that depict the lakes and effigy mound groups.

The university has grown in its acknowledgment of Native American culture, in some ways reconciling with several decades of expansion over Ho-Chunk lands.

Overall, Bird Bear said Native cultures present at UW is an attractive force to the university, and the American Indian Studies Program are not entirely vulnerable to losses in UW’s budget, although overall humanities does feel threatened.

“I’m not terribly worried about the American Indian Studies department,” Bird Bear said. “Any openings we won’t hire, any retirees we won’t hire. There are strategies, but it will be painful no matter what.”

Riley Vetterkind contributed reporting to this article.