A new one size fits all approach to addressing sexual assault on campus from the federal government could threaten students’ First Amendment rights, members of a free speech advocacy group said.

The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, along with several other organizations, issued an open letter to the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights and Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division in response to the department’s “blueprint” on how to handle sexual harassment on campus.

The blueprint was included in a letter to the University of Montana dated May 9 after an investigation into the sexual assaults of female students by football players at the school.

The proposal from the DOJ and OCR would change the definition of sexual harassment to include any “verbal conduct,” an inclusion FIRE said threatens free speech on college campuses.

Will Creely, FIRE’s director of legal and public advocacy, said the new definition could label any unwelcome speech protected by the First Amendment as sexual harassment.

“This could be a Sarah Silverman comedy routine, a discussion of “Lolita,” discussion of poetry in an English class or any imaginable speech that has to do with sexual or gender topics,” Creely said.

FIRE and its signatories, among which is University of Wisconsin political science professor Donald Downs, have asked the departments to retract and clarify its definition of sexual harassment.

Other signatories include professors at a number of universities, along with the National Association of College and University Attorneys and the American Association of University Professors, which Downs, an advisor to The Badger Herald, said had remained quiet on the issue of campus speech before this letter.

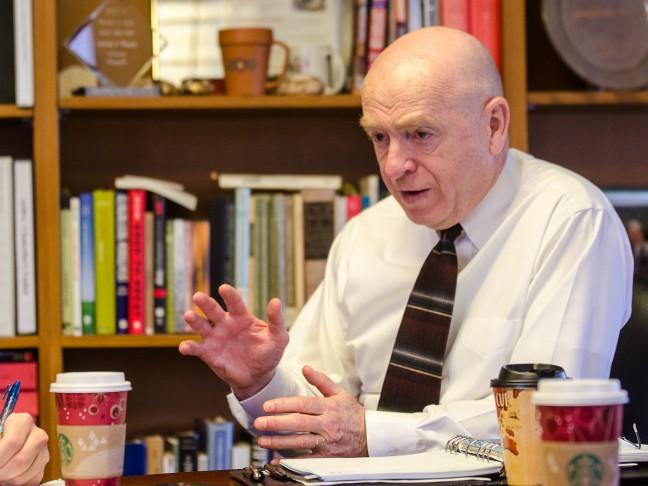

Downs joined FIRE as a signatory after working with the organization when it was founded in 1999. The proposed change could be too expansive to facilitate a strong intellectual environment, he said.

In addition to his concern about the educational atmosphere, Downs is concerned about the proposal’s creation without legislative or public input.

“We have too much government by bureaucracy and not by legislation,” he said. “In legislation, you have more access to the public, and there’s more input, comment and open criticism.”

Creely cited the case of Appalachian State University professor Jammie Price as an example of a possible consequence of this blueprint and is fearful more cases like hers could occur.

In May 2012, Price was placed on administrative leave because students alleged she created a hostile environment because of comments on the university’s handling of campus sexual assaults and for showing a film on pornography in her introductory sociology class.

“Students who are accused will find their names in a database, which will remain there indefinitely, and will be delivered to the federal government,” Creely said. “And there’s no idea of what happens to the database after that.”

While this database requirement is currently only for the University of Montana, he said it sends a message to other universities to conduct similar measures to avoid a costly federal investigation.

Creely added he would not be surprised if similar databases are implemented at universities nationwide by the fall.

Downs and Creely both said they hope the federal departments would retract the new definition and return to the definition defined by the 1999 U.S. Supreme Court case Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education that states the harassment must be offensive, targeted, objective, hinder a student’s ability to work or be educate and must be “persistent and pervasive” if in the teaching setting.

Creely added proponents of the measure see the definition as a way to encourage student reporting of harassment, which Downs said is the crux of the issue, not the law.

“If the Departments of Justice and Education want to encourage student reporting, they need to find another way to do it,” Creely said.