Patty Loew is used to being behind the camera, but when documentarist Mary Mazzio decided to tell the story of the Bad River Band of Lake Superior’s fight against Canadian energy company Enbridge, that changed.

Most tribal members were interviewed for the documentary during their Manoomin Wild Rice Powwow in August while Loew was in the middle of working with native teens for a tribal youth media workshop.

“I didn’t have time to be nervous, but it still was unsettling but rewarding because I think Mary had developed a really well thought out list of questions,” Loew said. “And the thing that I really appreciated about this documentary is she really allowed our community members to tell the story in their own words.”

Loew is a professor emerita at the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University. She’s a former producer and host at PBS Wisconsin and a former professor at the University of Wisconsin where she received both her master’s and Ph.D. in journalism and mass communication. Loew is also a citizen of the Mashkiiziibii Bad River Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe.

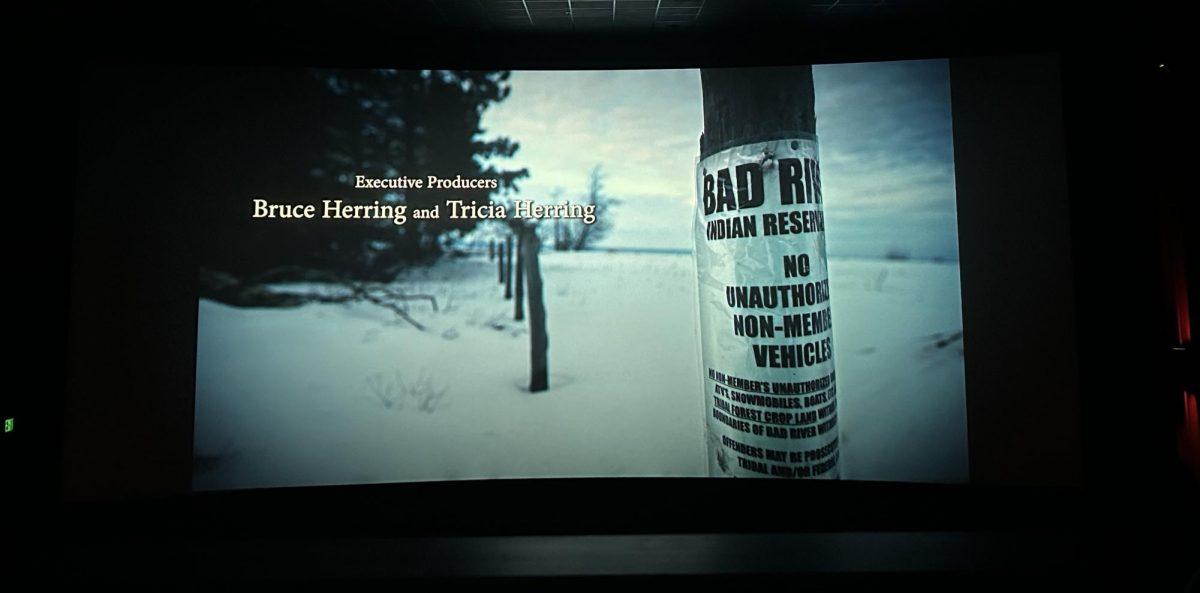

Currently, the tribe is resisting Canadian energy company Enbridge, which has 12 miles of oil pipeline running through the reservation. With the fear that the pipeline would rupture and pollute the waterways, the Bad River Band chose not to renew their contract with the company.

“We have 875 acres of wild rice in the Kakagon Sloughs, which act as a kind of the lungs of Lake Superior,” Loew said. “It filters the water, it provides nutrients for fish, it’s a nursery for sport and game fish. And it feeds animals, people and this pipeline — if it was to burst along our reservation — would threaten that.”

The Kakagon Sloughs are so important that they are on the United Nation’s Ramsar list of most ecologically sensitive places on the planet. But Enbridge refused to remove the pipeline, so the tribe took them to court.

This particular moment of history is just one chapter of the never-ending story of the Bad River Band’s resistance to environmental, industrial and governmental threats to their reservation, their culture and belonging for over 100 years.

“It’s kind of a David and Goliath story, because … our reservation was formed in 1854 and the state thought that we were now under its jurisdiction,” Loew said. “And [the state] didn’t understand the whole nature of a treaty, it being between two sovereign entities.”

Narrated by Edward Norton and Quannah Chasinghorse, “Bad River” comprehensively tells their stories through old and new footage, photos and retellings from tribal members. It also highlights some of the most heartbreaking moments of Indigenous history like boarding schools, which sought to assimilate native children into mainstream American culture.

The film also highlights a period in the 1950s when efforts were put in place to terminate reservations and relocate people to urban areas like Chicago and Milwaukee. As a part of this effort, Indigenous people were sent brochures with images of penthouse apartments with grand pianos and views of the skyline.

“Many Native people voluntarily left their reservations and traveled to the cities only to find out that it was a one-way bus ticket and directions to a flop house and now they were cut off,” Loew said. “If they were poor before on the reservation, at least they have family, at least they had these cultural connections. At least they had a support network.”

Many members of the tribe recount family members who struggled with addiction, homelessness, police brutality and homicides after moving to cities. One recounted that his parents moved to Milwaukee while he stayed in the reservation with his grandparents but when his parents came back, he didn’t recognize them anymore.

The film also shows scenes from The American Indian Movement, the Walleye Wars, trips to the Wisconsin State Capitol and other periods of resistance. Along with the voices of those in the Bad River Band, Mazzio employed Indigenous professors from around the nation who provided historical context, analysis and a deeper understanding of the generational experiences of Indigenous people.

The film concludes with a compilation of tribal members expressing commitment to conserving the land and sending messages to the future generation, with tribal members expressing their utmost love to those who will come after them.

Loew hopes many people will see this film and have the desire to act.

“I hope that it will prompt people to think about these issues when they go to vote” Loew said. “That’s the strongest measure of your commitment is to educate yourself about the issues and then vote accordingly.”

Additionally, several environmental organizations like The Lake Association, The River Alliance, The Timber Wolf Alliance and the Sierra Club Conservancy help fight against these environmental injustices.

Importantly, the story of the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe is not an isolated occurrence.

“It uses Bad River as sort of the Everyman,” Loew said. “It tells a bigger story through the resistance of this little Band of Ojibwe in Wisconsin.”

While a sense of perseverance and defiance is ultimately the main theme, one can’t help but leave the theater with a greater sense of respect for the land we live on.

The film will be shown in select AMC theaters — including AMC Fitchburg 18 — from March 15–28 with 50% of the proceeds going to the Bad River Tribe. Mazzio also shared it will be available for streaming in the distant future.