I got into writing film criticism for all the wrong reasons. It was because of a boy. He was a boy who I became friends with on Flixster, a now defunct site that brought together movie lovers through film reviews, “best of” lists and movie recommendations. Though I was once intrigued by the opposite sex, I have turned my devotion to the world of motion pictures. While before I maybe scrawled one or two sentence reviews, now I write thoughtfully researched, opinionated, artful reviews that take a lot of time and effort to accomplish. I have deigned myself a film critic in recent years, among an elite sect who dissect and obsess over every film they watch or want to watch, but in contemporary times, film criticism is no longer for the elite.

In the past, film criticism was an art form that balanced intellectual, thoughtful arguments on the content, form and technique of a filmmaker, with a critic’s general opinion. Print journalism became a platform for the topic and kept it relevant for 40-odd years. In that time film criticism was taken seriously, it held weight and it had high circulation because it mattered to the masses as well as the cultural select.

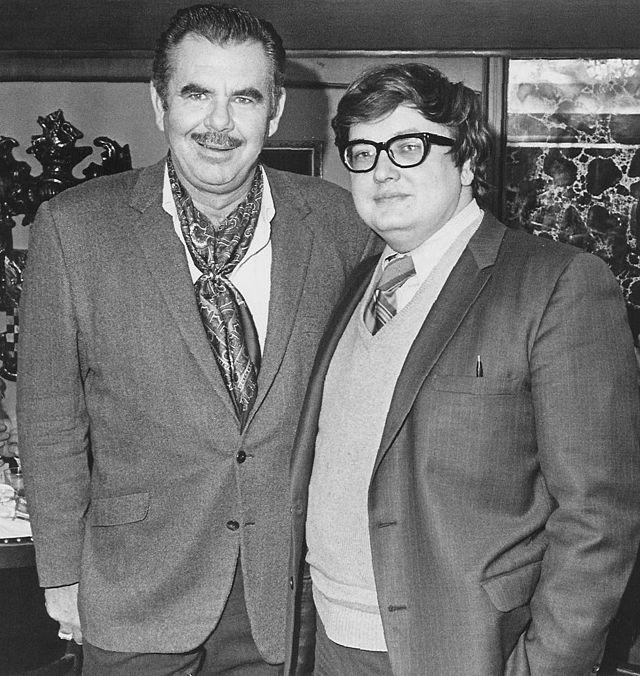

The most famous film critic of all time, Roger Ebert, won the first and only Pulitzer Prize in film criticism in 1975. He and Gene Siskel’s success in the field of film criticism led to the first ever television program concerning film reviews, called “At the Movies” which ran for 20-plus years. Film criticism became wildly popular because of this Public Broadcasting Service program, for the simple reason that Siskel and Ebert reviewed all films, including the worst of the worst. They made film criticism something that everyone could take part in, and stated that all films were equal, and deserved thoughtful discourse. The duo invented the motto “Two Thumbs Up,” and entertained through thoughtful disagreements that often turned heated.

In today’s world, film criticism is ubiquitous, open to amateurs and much more prevalent. There are good and bad things pertaining to this change, which has resulted mostly through the Internet’s boom. Like me, many people write reviews of films on social media or on different film websites, including Rotten Tomatoes, IMDb and Metacritic. This means that today can be seen as a golden age for film criticism, as there are more people reviewing films than ever before. Opinions that may never have been thought over or given credence are now on the web for all to see, which means that more films are being recommended and seen than ever before.

What’s generated from this mass interest is various websites’ need for buzz for their pages. This leads to a lot of clickbait, which are links to articles which only exist to generate a site’s traffic. Many top lists, articles and reviews are written without care, just to produce ad revenue. This leads to shoddy criticism that often critique weak, clichéd films instead of ones that actually deserve the attention, like independent features, films directed by women or minorities and foreign films.

There are also a lot of amateurs among the ranks of online critics who don’t pay close attention to what they write, who don’t care about history, or technique or how this particular film fits into regular genre conventions. As someone who started out as an amateur and someone who still needs instruction in this art form, this isn’t as big a problem as many older critics would have us think. Everyone has to start somewhere, even if it’s just spewing out a couple sentences on a recent superhero film.

Nowadays, there’s no major critic who is right in the forefront of people’s minds. Siskel has been dead for 15 years, and Ebert died this last year. Today the more finessed critics are writing with an elitist flair, without regard over whether the reader engages with the piece at all.

Film criticism is rarely written for those just going to see a movie in theaters, but more for those who count Renoir and Kurosawa as the best, and only, auteurs worthy of praise. It’s not that this brand of criticism isn’t wanted, but that it’s not as needed. People want concise sentences that give them a general picture of what they’re going to see. They do not want to wade through the missive of an aging philistine with a bone to pick with major studios.

Still, where will our film culture go if not for its critics? Without the stalwart presence of Roger Ebert, who is going to take on the big studios, who are peddling out schlock left and right? Who will question unfair practices of the MPAA, or confront clichéd, hollow performances from well-paid actors? Without those who question those in power, where would we be? Great, impactful films are a dying art as of late, at least compared to major studios’ output. Though it may be the unpopular opinion, film criticism needs to stand the test of time, and it needs a leader to do so.