Jim Goodman had high hopes for his dairy farming business. After spending the bulk of his adult life milking and caring for his 45-cow herd outside of Wonewoc, Wisconsin, Goodman wanted to pass his life’s work on to the next generation.

His plans fell through, however, when a young couple reneged on their investment, forcing him to sell his cows for a much cheaper price to a larger farm in 2018.

In the years since giving up his herd, Goodman channeled his frustration into activism and rose through the ranks of the National Family Farm Coalition before becoming the organization’s president. Still, he remains saddened by the turn of events that preceded his early retirement.

“We could see that it was only a matter of time until our small farm was just not viable,” Goodman said “The cheese factory that we were selling to was losing its market share because of cheaper products produced by bigger companies, and they basically told us they wouldn’t be able to buy our milk anymore. There just weren’t any other options.”

The story of Goodman’s farm reflects a fast-moving shift in American demography — the consolidation of agribusiness followed by the hollowing out and graying of rural communities.

For family farmers like Goodman, the fate of Wisconsin’s rural counties and towns are inexorably linked to the business model for agriculture — a business model that increasingly emphasizes high production rates for foodstuffs and rewards corporate control of farms and their produce.

Competing with corporations

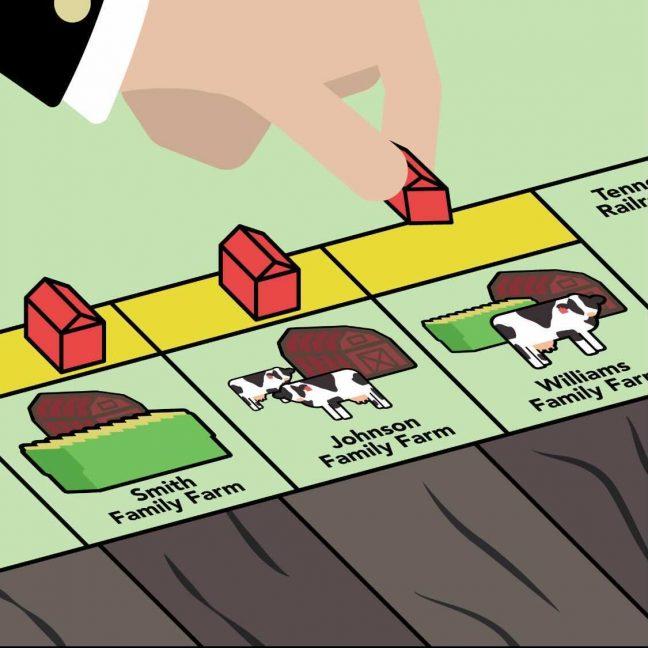

It is no secret that the idyllic image of agriculture — red barns, small herds of grazing cattle and family-owned farm houses — is rapidly disintegrating.

Wisconsin recently recorded the highest rate of farm closures in the United States, losing 69 farms in 2020, a net-increase of 12 from the previous year. In their place, large industrial-scale factory farms now dominate the market.

Factory farms — also known as concentrated animal feeding operations — gained popularity in the 1960’s, and are defined as using extreme confinement of a high number of livestock for commercial use. The practice was designed to generate a high volume of food in a short period of time and often relies on packing thousands of animals into tight quarters for production. The minimum number of cows needed to classify a dairy operation as a CAFO is 700.

These large-scale farming operations are frequently owned or directly financed by larger companies. Target, for example, unveiled its own line of produce in 2019.

The rapid consolidation of agriculture left small farmers and activists in dismay. Family Farm Defenders Executive Director John Peck said corporate insertion into agribusiness blindsided dairy farmers who are now on the verge of losing their market altogether.

“Some of them have these contracts where they’re providing milk for big cheese makers like Sargento who get their milk from a very small handful of giant factory farms,” Peck said. “Some of the big retailers like Walmart are now even setting up their own dairy farms. They’re not going to be buying from farmers anymore.”

In addition to their well-documented history of alleged animal abuse, corporate-contracted CAFOs also pushed smaller farms out of the industry at a breakneck pace. Between July 2020 and June 2021, 48 farms in Wisconsin filed for bankruptcy, exceeding the state with the second-most filings by 17. In 2019 alone, the state lost 57 farms.

Peck said Wisconsin lost half of its dairy farms since the turn of the century and that large, corporate-contracted factory farms currently control 25% of the market, despite accounting for less than five percent of the state’s dairies. In 1987, the average number of dairy cows per farm was 80. Just 15 years later, that figure reached 275.

The continual decline in family farming is accelerated by an economic structure that emphasizes quantity above all else. The average cow produces roughly seven gallons of milk a day, meaning a farm with 1,000 cows can produce 7,000 gallons in 24 hours, whereas an 80-cow herd can produce just 560 gallons a day.

Peck said companies such as Grassland Dairy are not only turning to factory farms as primary producers, but are also actively propping up factory farming as an alternative means of production.

“Two years ago Grassland basically cut off 70 or 75 smaller dairy farms in Minnesota and Wisconsin,” Peck said “They basically threw a bunch of smaller dairy farms under the bus, saying that there wasn’t enough demand to keep buying their milk to make butter, but at the same time, they’re pushing for a giant factory farm in southwestern Wisconsin.”

As the corporate takeover of agriculture persists, farmers are presented with a daunting choice: go big or go bankrupt.

Due to their experiences with the hostility of today’s agricultural market, Goodman and Peck were both clear in voicing support for small farmers who grew their herds as a product of circumstance, with Goodman calling a debate between small and large family farms a “false conflict.”

Rep. Dave Considine, D-Baraboo, of the Wisconsin State Assembly said the current economic landscape left many locally-based farms no choice but to scale up their production in order to compete with big agribusiness. Those who can not afford to expand their operations often face foreclosure.

“We have to differentiate between company-owned farms and large family-owned farms,” Considine said. “There are a lot of Wisconsin dairy farms that are really family farms that just grew to support a family.”

Controlling the market

The rapid consolidation of the agriculture market occurred in large part because corporate America was allowed to gain a stranglehold over each step of the supply chain.

After a relaxation of antitrust laws during the Reagan era, companies moved to buy up the production, distribution and processing of dairy, meat and crops.

Today, four corporations own over 50% of the farm to table supply chain. After the corporate buy out of agribusiness that unfolded as a byproduct of 1980’s trickle-down policies, companies became free to pay farmers historically low wages for their products, even as the retail price for milk continues to rise.

Yet, thanks in large part to a limited number of buyers, farmers are often unable to find alternative markets and are forced to settle for low prices.

“If you go to the grocery store, you see thousands of products,” Goodman said. “So people think ‘the system must be working really good, because look at the selection I have,’ but there aren’t that many companies producing food. They’re just different brand names that have been bought up. There just is not an option for farmers to market anymore.”

The absence of a diverse market places farmers in a bind. In order to remain operational, family farms often sell their products to a select number of companies who often rely on monopolization and cheap factory farm produce to fund their operations.

“The big meat companies are basically holding their suppliers captive,” Goodman said. “So, they’re really not independent producers.”

Thanks to their aggressive expansion and dominance over the supply chain, factory farms are now too big to fail. As a consequence, larger farms are often given priority for federal aid over family businesses.

During the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic, the top 10% wealthiest and largest farming operations netted the lion’s share of bailout money, earning 60% of federal dollars. The bottom 10% of farmers, meanwhile, received just 0.26% of relief funds.

In the pre-pandemic years of the Trump administration, 82 factory farming operations acquired more than $500,00 in stimulus payments while the bottom 80% of farmers received $5,000 on average.

Peck said he knows a dairy farmer who received a single dollar in federal aid.

Leveling the playing field

President John F. Kennedy once said, “The farmer is the only man in our economy who buys everything at retail, sells everything at wholesale and pays the freight both ways.”

In perhaps no other area are the former president’s words more applicable than the dairy industry.

The cost of producing milk in Wisconsin was $22.70 per hundredweight in 2020, yet the price of milk reached as low as 12.95 per hundredweight during the same year.

The decline in milk prices can be attributed in part to the rise of factory farming. As industrial farms pump out thousands of gallons of milk which are then purchased by large companies, the price naturally falls as supply exceeds demand.

The result is a market which is highly profitable for corporate agribusiness, yet leaves small farmers financially stranded. Nationwide dairy production rose by a factor of roughly 100,000lbs between 2005 and 2018, even as the U.S. lost over 10,000 farms during the same period.

The volatility of the agriculture market leaves producers in a state of perpetual financial uncertainty, as a farmer could receive drastically different prices for the exact same product on a month-to-month basis.

For all intents and purposes, farming is among the only professions in America that does not guarantee a minimum wage.

To offset the plummeting price of milk, some farmers are calling on elected officials to implement a price floor for agricultural goods. These price floors, which would be adjusted for inflation, are designed to guarantee a minimum price for a given agricultural product and provide a lifeline to farmers like Goodman.

“In the system we have now, prices that vary so widely,” Goodman said “It’s very hard for anyone to make a decent living and plan for the future if they have no idea what they’re going to be getting paid in the next month or a year. I think price floors will give [farmers] some stability about what they’re going to be getting paid, and what things are going to cost them.”

Price controls alone will not alleviate the stress factory farms put on rural economies. A reversal of current trends will likely require a complete overhaul of the agricultural industry and a bottom-up reinvestment in small-scale agriculture.

A potential solution posed by environmentalists and small farm advocates alike is a moratorium on factory farming. Such a moratorium would place a cap on the number of factory farms allowed in the country and facilitate a redistribution of farm aid. A moratorium could serve as an alternative to growing calls from climate activists to abolish the factory farming industry.

Considine said he is not prepared to support an outright ban on factory farming, but believes a moratorium should be on the table.

“In some ways, that makes a lot of sense,” Considine said. “Not to say you can’t ever do it anymore, but let’s take a minute and take a pause. Let’s really study the effects of this [factory farming].”

UW students challenge big agribusiness

For their part, UW students appear to understand the gravity of Wisconsin’s ongoing farm crisis.

Groups such as Slow Food UW make a point to work almost exclusively with small farmers when preparing and distributing their meals.

Slow Food UW is an offshoot of Slow Food — a decades-old organization which prides itself on functioning as an alternative to fast food companies. The organization’s executive director and UW senior, Emma Hamilton, said the mission of Slow Food coincides with a commitment to collaborating with family farms delivering fresh ingredients.

“Slow Food aims to make eating good food that is locally sourced and sustainably produced accessible to as many people as possible, and we do that in a lot of different ways,” Hamilton said. “We get as much fresh produce from local farmers as possible.”

In addition to buying ingredients from small farms, Hamilton said Slow Food actively networks with farmers at locally sourced farmers markets.

Hamilton described Slow Food’s relationship with local farmers as one which is based in both a desire for community building and respect for those producing food.

“For us, it’s about making connections with the farmers that are at the farmers market, and wanting farmers to know we love supporting them,” Hamilton said “I think having that relationship with farmers is important and just respectful.”

Student-led efforts to invest in family farming may prove to be a pivotal step in shifting away from industrial agriculture, yet Goodman expressed frustration with UW as an institution. Goodman cited research conducted by the university with backing from large corporations which centered around refining the same practices driving locally-based farmers to the breaking point.

Among the top donors to the Wisconsin Center for Dairy Research’s Campaign to Secure Wisconsin’s Dairy Future were Sargento Foods and Land O’ Lakes Inc., with Sargento Foods CEO, Lou Gentine serving as the project’s co-chair. One of the major partners of the Marshfield Research Station is the USDA’s Institute for Environmentally Integrated Dairy Management, an organization which specializes in researching milk production and dairy cow performance.

Goodman said he feels UW’s current research focus contradicts the university’s stated mission to promote the wellbeing of all Wisconsinites. Goodman said there is a need for research examining topics such as soil and animal health as opposed to studies focused on obtaining the maximum production out of an animal.

UW College of Agriculture and Life Sciences News Manager Nicole Miller said in an email statement to The Badger Herald that the school has faculty members dedicated to animal welfare as well as federal grants to study topics in sustainable agriculture like dairy farm greenhouse gas emissions.

CALS also hosts field days each year to share best practices with the state’s farmers, and the Center for Dairy Profitability aids farmers with succession planning by providing guidance on transferring farms to the next generation.

“[CALS] is dedicated to supporting all types of agriculture across Wisconsin, the nation and the world,” Miller said. “We are always open to hearing from members of the agricultural community about ways to better serve them, including collaborative research projects.”

Miller said farmers who would like to collaborate with the university or have concerns should reach out directly to CALS.

Even with his concerns, Goodman is still hopeful UW will chart a new course and shift the focus of its research to encapsulate what he described as the Wisconsin Idea.

“The university said it’s redefined Wisconsin Idea would center around the general welfare of the entire state,” Goodman said. “I want to see them to live up to that.”

Adverse Effects

Even as farmers, students and other organizations work to combat the immediate impacts of increasing mass agricultural production, the ripple effects of a consolidated agriculture market can be seen in the sharp decline of rural economic activity.

Between 2010 and 2018, two-thirds of Wisconsin’s rural counties experienced a drop in their populations.

According to the Wisconsin Office of Rural Health, 12% of rural Wisconsinites experience poverty, and almost one in five children live below the poverty line. The average unemployment rate for Wisconsin’s rural counties was 6.4% in 2020.

Any hopes of a potential surge in revenue from factory farming appear to be dashed by a continuing decline in labor force size and the number of businesses hiring workers, even as industrial farming expands. Langlade County, for instance, saw a 6.5% drop in the labor force and a 7.9% drop in the number of businesses countywide between 2010 and 2018.

From his perspective in the legislature, Considine described the ongoing trend as a predictable consequence of a truncated market. While factory farms may support a significant network of employees, Considine said laborers hired from outside of the community fall short of providing the same economic benefits as local farmers.

“In regards to money circulating in the local economy, the smaller farm does a better job of improving our local community and supporting our local businesses, whatever they may be,” Considine said.

For Peck, a farmer himself, the slow death of family farming is a far more sentimental issue.

Peck views the continued loss of small farming as an identity crisis for Wisconsin — a state whose dairy farmers pride themselves on the quality of their products and the ability to support their communities.

“Farmers I know don’t want to get an award for selling the cheapest, lowest quality milk possible, and that’s what’s so sad,” Peck said. “Our entire identity is being destroyed by an industry hell-bent on being the biggest, baddest dairy producer ever. That’s not our niche in the world.”