In the early morning hours of Aug. 24, 1970, a mysterious van parked unnoticed outside Sterling Hall on the University of Wisconsin campus.

At 3:42 a.m., dynamite set off the massive amounts of ammonium nitrate and fuel oil packed into its hull by four young radicals enraged by the United States’ ongoing role in the Vietnam War and the Army Mathematics Research Center’s home in the upper floors of Sterling Hall.

The bomb produced a blast that shook homes for miles around, damaged at least 26 campus buildings, shattered years of physics and astronomy research and left 33-year-old physicist Robert Fassnacht dead.

Across the isthmus, people sat up in their beds at the rumbling of the explosion and thought one thing:

“Army Math.”

Long before 1970, Madison attracted students stirring for change in the U.S.

Paul Soglin, a noted activist who went on to be mayor of Madison, remembers arriving as an undergraduate in 1962 at a campus with already strong civil rights and peace movements. Opposition to discrimination and the proliferation of nuclear weapons ran high, and in 1964 the lynching of three civil rights activists in Neshoba County, Miss., outraged campus. One of the victims, Andrew Goodman, was a former UW student.

As the decade progressed, however, energy in Madison increasingly shifted toward the developing Vietnam War. In October 1963, UW saw its first anti-war protest in the form of a few hundred people gathering on the steps of Memorial Union. Over the next seven years, the movement grew from “a couple hundred people to literally tens of thousands in Madison,” Soglin said, its numbers swelled by an unpopular draft targeting youth who at the time were too young to vote.

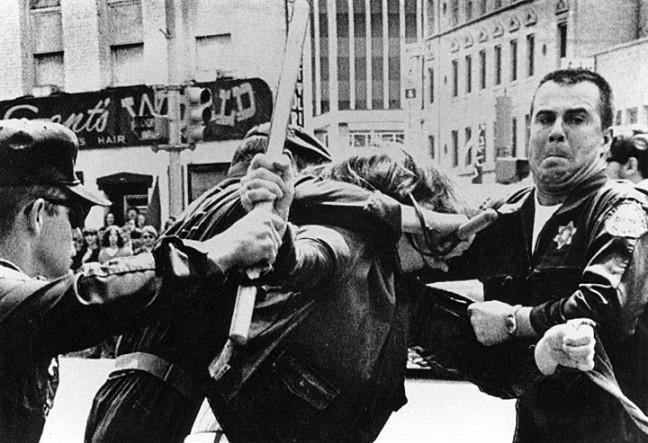

Increasingly, local and national violence radicalized members of the disillusioned in Madison. Campus got its first taste of police brutality on Oct. 18, 1967, when protestors, upset the university was again allowing Dow Chemical Company to recruit on campus, poured into Commerce Hall, now known as Ingraham Hall. Campus officers and administration called in city police as backup, who in the end resorted to beatings and tear gas to clear the building.

From there, tension in Madison escalated. In 1969, the first Mifflin Street Block Party was intended to be an anti-war dance. Instead it descended into a riot. Students for a Democratic Society grew into a powerhouse for activism on campus, regularly attracting thousands of people to its meetings and organizing demonstrations. Nationally, the organization became known for its radical nature and spawned movements such as the Weather Underground Organization.

Soglin said throughout this time, the anti-war movement in Madison remained focused on civil disobedience and passive resistance. Based on these tactics, protesters might obstruct a site and take the consequence of being arrested, never fighting back in the process.

“I would say that 99 percent of the students were activists within that construct,” Soglin said. “Then there was just a very tiny percentage who, for lack of a better name, I refer to as the crazies. These were the ones who thought America was ready for armed revolution.”

Mary McComb, now a part-time lecturer at UW-Stevens Point, remembers being drawn in by the energy of the isthmus’ radicals as a resident of Mifflin, which was considered the epicenter of Madison activism at the time.

“We all thought that we were going to have to save the world,” McComb said. “I remember people my age or a little bit older had guns because sooner or later it was going to be out on the streets, and you were going to have to fight. I remember hiding a bunch of guns in my lingerie drawer.

“It made perfect sense to me to have guns in my drawer.”

In 1970, the invasion of Cambodia whipped the nation’s students into a fervor, resulting in the tragic fatal shooting of four students at Kent State University on May 4 and two at Jackson State on May 15. By the summer of 1970, the National Guard had been called to campus twice to quell student unrest. The “crazies,” though relatively low in number, were becoming increasingly visible at UW.

Under the cover of night on Dec. 28, 1969, Karl Armstrong, an on-and-off UW student horrified by the war in Vietnam, tossed a firebomb into an ROTC classroom located where the Microbial Sciences building now stands.

It was the first in a string of winter bombings that targeted military-affiliated buildings. On Dec. 29, with his brother Dwight piloting a stolen airplane, Karl Armstrong dropped a series of explosive-filled jars, which failed to detonate, on the Badger Army Ammunition Plant in the Baraboo Hills.

A later firebomb struck the Red Gym, and failed attempts hit the Primate Laboratory –meant for the state Selective Services headquarters across the street — and the Sauk Prairie substation, which supplied power to the Ammunition Plant.

The attacks were heralded in student media outlets like the Daily Cardinal as essential efforts against the war, and after an endorsement by local underground newspaper Kaleidoscope, the mysterious group became known as the “New Year’s Gang.”

Meanwhile, Army Math had become a focal point for anti-war efforts on campus. Its removal was demanded by SDS under the slogan “Bring the war home.”

And in the summer of 1970, the New Year’s Gang, which now included 24-year-old Karl Armstrong, 19-year-old Dwight Armstrong, 18-year-old David Fine and 22-year-old Leo Burt, turned its sights on Army Math’s destruction.

“They believed things had reached such a horrid state in terms of what the Nixon government was doing … that it was the obligation of students to become part of a resistance that waged war against the war machine,” Soglin said.

The bomb was packed into a stolen Ford Ecoline van left parked outside Sterling Hall early that August morning. It shattered Army Math’s windows, but left its work almost untouched. Instead, the blast shattered the radical faction of the antiwar movement in Madison.

The story of the Sterling Hall bombing is twice as old as many students at UW and yet, year after year, it is recounted on tours, whispered among students and revisited in the pages of local newspapers as a tragic piece of campus history.

But its legacy as the moment that broke the radical movement is its greatest. Evident today, that peaceful refocusing returned Madison activism to what Soglin said are its roots in the civil rights era.

Even for Heidi Fassnacht, who was 11 months old when the bomb killed her father, that message is absolutely essential when looking back at the context of the times and the state of student involvement in 2010.

“There’s a sense of people playing at revolution. There’s that energy there. But when my father died, it was a reality check. It was a ‘Wait a minute, this isn’t just a game,'” she said. “That’s one of the things I’ve been realizing more. It really was a gift.”

With the U.S. involved in unpopular foreign wars, emotions running high in the gay rights movement and rampant questioning of the accessibility of the American education system, that could prove to be a salient message.

Max Love, a UW sophomore and former Associated Students of Madison representative also involved in Student Labor Action Coalition, said smart student activism has shifted to focus on novel instead of highly visible, in-your-face tactics to get the attention of those in power.

SLAC member and UW junior Jonah Zinn said two of the greatest victories at UW during the past two years — the cutting of apparel contracts with Russel and Nike –came only after SLAC and other student groups nationally drew attention to them through peaceful means.

Tactics like these mean few believe students to be on the verge of armed revolution. Instead of a respect for peaceful protest and working through the system, however, some liken the current state of student activism to something deeper.

History professor Joe Elder, who also taught on campus in the ’60s and ’70s, said general student interest in current U.S. wars amounts to “a numbness” that dates to demonstrations against the beginning of the Iraq War in 2003 that went unacknowledged in foreign policy.

“The level of suffering has sort of reached a level where people can kind of say, ‘Well this is what we’re doing in this part of the 21st century.’ It’s almost part of a way of life to acknowledge that every week there are going to be more young Americans, more young Iraqis killed,” Elder said. “There’s a weariness.”

Paul Buhle, who founded the SDS-centered journal Radical America and went on to become a notable author and scholar on radicalism, said rising tuition at UW has also contributed to a student population dominated by the well-off. Because, like the Vietnam War, current U.S. wars draw troops from lower economic backgrounds, most veterans who attend school upon their return choose cheaper options.

“If you were to go to some other campuses, people have told me that they have a lot more people coming back from Iraq in their classes, ” said Buhle, who earned a Ph.D. from UW in 1975 and is now a Madison resident. “We’re cushioned from some of the worst effects of the war.”

Soglin said overall, the current generation simply has less appreciation for the benefits they receive from the greater society, perhaps making them less inclined to fight hard and publicly for a voice.

“The negative side — and I’m not the one that came up with this — is this present generation may be the one that has less empathy than any other generation since World War I,” he said.

National shows of student mobilization are rare now, said Angus Johnston, a student activism historian who teaches at the City University of New York, though he believes a surge in activity is happening at the campus level. However, he noted March 4 as a recent national movement, when students across the U.S. rallied in support of greater accessibility to higher education.

Though UW had little involvement, mobilization around the day will likely continue in the coming years. Johnston also expects October 7 to be a major point of national action, when students will rally against current financial policy.

“I’m really skeptical of the whole decline in empathy argument,” Johnston said. “[The anti-Vietnam War effort] wasn’t about being empathetic and trying to help people in other parts of the world. That was about students who were [worried about the draft and] looking out for their own interests.”

Love said the face of student involvement has simply changed, and today extends to students involved in recreational sports, the environmental movement and beyond.

Though their action may not appear direct, their passions all provide means to contribute to a better community, Love said. Their work is borne out peacefully in dozens of advocacy groups at UW, including popular student unions, marches and rallies on spaces in Library Mall well-worn by activists of the past and student governments like ASM.

Still, the question remains if students are also acting on lessons learned from the past. Despite its place in the history of campus, quick turnover means many students miss the story of Sterling Hall.

“Whether [students] know about the Sterling Hall bombing or not, it seems like having the conversation so you can avoid violent confrontation, that would be more important to me,” Heidi Fassnacht said.

After slipping through the fingers of local authorities after the Sterling Hall bombing, the New Year’s Gang remained on the run, now threatened by the eyes of thousands aware of their new spots on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list.

In 1972, Canadian authorities caught up with Karl Armstrong in Toronto, Canada. The next year, he was returned to Madison where he was sentenced to 23 years in prison for his leading role in the bombing and death of Robert Fassnacht. He served seven.

Fine was arrested in 1976 and Dwight Armstrong in 1977. Both were sentenced to seven years and served three.

Though shortly after the bombing newspapers carried their regret for Fassnacht’s death, the New Year’s Gang’s remorse for the bombing has been portrayed by the media as low.

Soglin noted that in 1989, Karl Armstrong made a different sort of apology.

“This time he apologized for the anti-war movement. He apologized for what the New Year’s Gang did to disrupt it, to weaken it,” Soglin said.

Today, Karl Armstrong lives in Madison and owns the Loose Juice vending cart, which regularly pops up on Library Mall. Dwight Armstrong, who also remained in Madison, died of lung cancer in June at UW Hospital. Newspapers across the U.S. ran his mug and stories of his involvement in the bombing.

Fine works as a paralegal in Portland, Ore. At one point, he was blocked from becoming an attorney after passing the Oregon Bar exam due to his role in the bombing of Sterling Hall.

Authorities caught up with Burt in Canada shortly after the bombing but failed to capture him. Over the years, he remained on the FBI’s wanted list, and thousands of tips poured in to aid the case.

He was never found.

Related articles:

Original article on bombing from 1970, with timeline: Protest Activity Reaches a Terrible Superlative