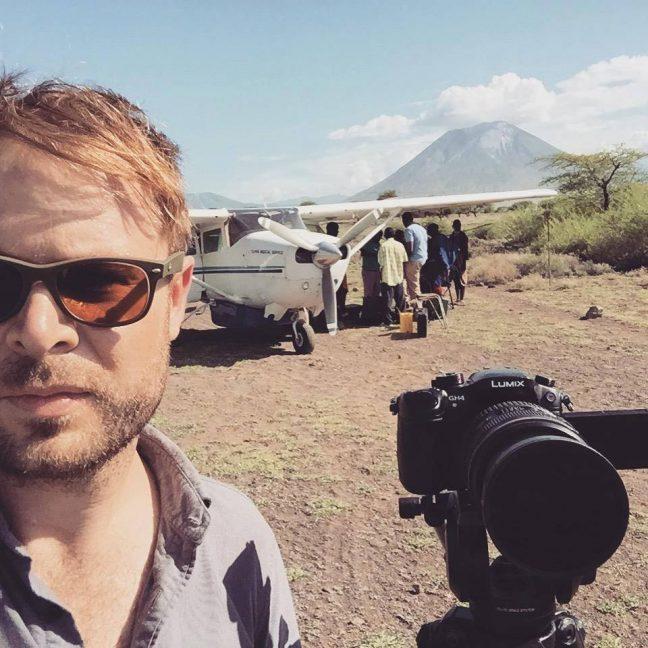

Aaron Ohlmann films those who don’t have a way to tell their stories, in the hopes that the world will empathize with them.

The University of Wisconsin alum is now a traveling documentary director who has shot in over 50 countries, often revealing and unpacking the humanistic nuances of issues that mainstream media ignores.

Ohlmann’s latest work are episodes of the second season of Viceland’s Black Market series, which starts Tuesday, in which he captured the day-to-day lives of poachers in one episode and Japanese yakuza, members of organized crime units, in another.

The Badger Herald talked to Ohlmann about what he’s been up to, where he wants to go next and the importance of his work.

The following interview has been edited for style and clarity.

The Badger Herald: In these Viceland episodes, do you make any effort as a director to portray your subjects as sympathetic.? Or do you try and simply portray them in plain light and let them tell their stories themselves?

Aaron Ohlmann: The idea behind the Black Market series is to tell the stories of people who have been marginalized by the system and follow the underground economies that emerge when people are forced to improvise to survive.

In the segments I produced, we’re telling the stories of poachers and gangsters, but of course there’s a far more complex reality behind those terms. These are deep human stories. Whether you agree or not with the choices they’ve made, you have to empathize with the people you’re filming. That’s the job, and it’s not difficult.

When you’re in the same room with a human who feels like they’ve run out of options and has their back against the wall, it’s impossible not to empathize. We’re all human. We’re dropped on this rock that’s careening through space, constantly subjected to overwhelming forces over which we have very little control. We all do what we can.

BH: Did you ever fear for your life during the filming of those episodes?

AO: I’ve never been in fear for my life, but there are moments when you find yourself in intensely surreal situations. There was a moment when we were deep in the jungle in Cameroon when I realized I felt much safer and comfortable with the poachers than I did with some of the forest rangers. The poachers welcomed us into their homes and shared food with us, while the rangers were really quite threatening and cruel —not what I expected going in.

BH: What advice would you give film students at UW who want to get into the kind of work you do?

AO: I don’t think I’m really in a position to offer much advice. Werner Herzog has some ideas.

BH: What’s one country and topic you haven’t gotten to film but desperately want to?

AO: I think that the current refugee crisis demands our attention, and while I’ve had a chance to engage on the fringes of that topic, I hope to do more. I’m just getting home after a month in Northern Iraq, where the conflict with ISIS is escalating to the point where the UN expects over a million people to be displaced this year. We’re currently witnessing one of the largest humanitarian disasters since World War II, and as we speak, Iraqi and Kurdish tanks are rolling toward Mosul. It threatens to get much worse before it gets better. I think that’s where my attention will be focused in the coming months.