Three Universities of Wisconsin branch campuses are set to shut down at the end of the academic year, leaving students scrambling to transfer to larger campuses and communities reeling from the loss of their local campuses. Marinette, Fond du Lac and Washington Counties will soon lose their local UW campuses due to diminishing enrollment rates. These campuses offered students two-year liberal arts programs and a mode to begin their bachelor’s degrees before transferring to a four-year campus.

Most importantly, these campuses allow students the opportunity to ease themselves into higher education. A history professor at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh’s Fond du Lac branch told The Cap Times that many students who attend these local campuses are from small, rural towns or are non-traditional students that require the academic support and affordability offered at small, local campuses. The closure of these academic institutions can make entry into higher education increasingly inaccessible to Wisconsin residents.

Per The Cap Times, Ben Kannenberg is a student at the Washington County branch of University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee that was able to reenter higher education via this local, affordable campus after failing out of the University of Wisconsin. Kannenberg claims that the Washington County branch provided him with more interaction and support from faculty members in contrast to the large, impersonal classes he attended at UW-Madison.

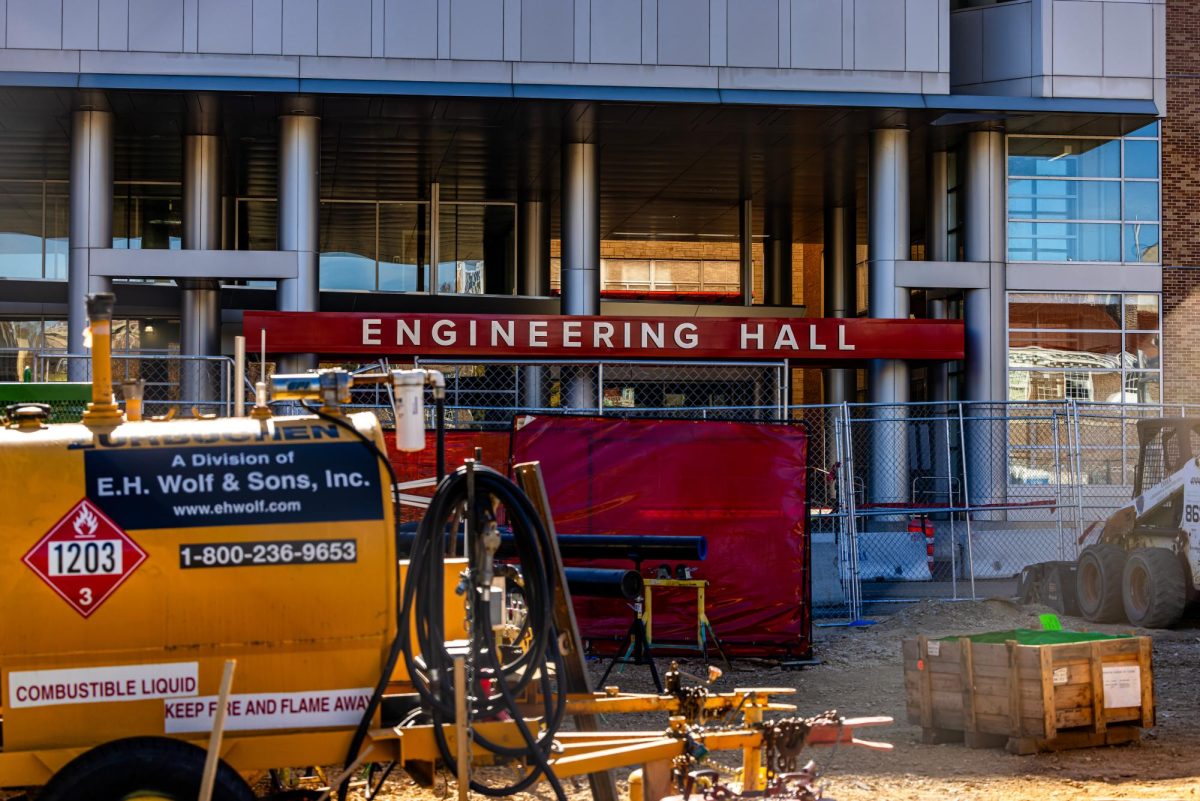

NIH grant further establishes UW as research, STEM institution

The Washington campus served as a safety net that eventually propelled Kannenberg back into the pursuit of a four-year degree. Without these local campuses, students that require a more individualized education will no longer have the option to begin their academic journeys at these local institutions. In other words, these students are at greater risk of falling through the cracks at large, public institutions.

Matthew Caine, student at UW-Oshkosh’s Fond Du Lac campus, told the Fond Du Lac Reporter that transferring to UW-Oshkosh’s main campus will not be a viable option for many of his nontraditional classmates who have full-time jobs or children.

Alyssa Ratledge, a research associate at a national nonprofit told PBS Wisconsin that the gradual closure of two-year colleges contributes to the formation of “education deserts.” Ratledge claims that the stereotype of the college experience involves students traveling far from their homes and living on campus.

But in reality, the majority of college students commute and attend classes within 25 miles of their home, according to Ratledge. She further claims students from rural towns are less inclined to leave their local communities, making local two-year institutions their entry point into higher education.

Republicans aren’t serious about marijuana reform. A State Supreme Court case might change that.

Ratledge believes that forcing rural residents into urban areas to pursue higher education will further deprive rural communities of demographic and economic development. While trade schools exist in small Wisconsin towns — such as the Moraine Park Technical College in Fond Du Lac — UW branch campuses provide a unique opportunity for students to pursue degrees in liberal arts and utilize resources associated with four-year institutions.

Spectrum News also attributes the shutdown of branch campuses to a decrease in funding from the state. Gov. Evers’ proposal to reduce tuition for students with a family income below $60,000 was not approved by the Legislature, creating great burdens for UW schools to increase enrollment after the economic crisis associated with the Covid-19 pandemic.

Additionally, the UW System is facing a budget loss of $32 million, leaving all but two UW schools with a budget deficit. With the four-year campuses reeling from the effects of this loss in funding, UW’s satellite campuses are in grave danger of losing support from these main campuses.

Age limits for Wisconsin justices balance responsiveness, experience

But the economic burdens associated with declining enrollment at these two-year institutions cannot be overlooked. It is not sustainable for the UW System to use its limited funding and Wisconsinites’ tax dollars to fund programs that are not demanded by communities. But without the branch campuses, rural communities are in danger of being locked out of the UW System entirely, furthering existing urban-rural inequities.

In order to combat these burdens, UW System President Jay Rothman suggests solutions such as offering graduate programs and expanding dual enrollment programs for high school students. It is clear that these creative solutions will be required if the branch campuses are to be sustained. In fact, investing in early college programs for high school students in rural areas may prove to be a successful method to help them jump-start their college careers. This might be especially impactful as rural communities struggle with accessibility to dual enrollment programs.

If enrollment rates and budget cuts persist, UW’s remaining branch campuses face an uncertain future. But it is important that legislators and university authorities fight to sustain these local campuses for the sake of equity in higher education. Higher education is not only linked with economic development for students, but it has far reaching implications. For instance, access to higher education is a social determinant of health outcomes. To avoid depriving rural Wisconsinites from their right to pursue higher education, the state must take creative action to maintain branch campuses in rural communities.

Aanika Parikh ([email protected]) is a sophomore studying molecular and cell biology.