Note: This story uses person-first language (“people with disabilities”) and identity-first language (“disabled people”) interchangeably, per the mixed use in various interviews. Please note that people may prefer either term or different terms.

One day in fall 1994, University of Wisconsin law student Brigid McGuire rolled up to a desk, revved up an electric saw and cut it in half to make room for her motorized wheelchair.

This moment was the final straw for McGuire. She had received nine parking tickets in one semester. Her offense — the inability to find parking close enough to the law building to accommodate her disability. At one point, an assistant dean had McGuire arrested for trying to prevent her car from being towed after parking in the grass on Bascom Hill during construction.

McGuire’s struggle and act of defiance came four years after March 1990, when hundreds of disability rights activists abandoned their mobility aids to pull and drag their bodies up the steps of the U.S. Capitol to bring awareness to the need for legislation ensuring access for people with all kinds of disabilities.

This protest, known as the Capitol Crawl, inspired the landmark Americans with Disabilities Act to be signed into law in July 1990.

While smaller pieces of legislation provided some federal protections, the passing of the ADA is known as a critical moment for disability civil rights law, as it has attempted to ensure equal access in all spheres of public life, including education, entertainment and employment. In the realm of higher education, this means students, staff and faculty are entitled to accommodations that facilitate full participation in teaching and learning.

Though the ADA can provide countless accommodations to the UW campus community, McGuire’s story shows it doesn’t mean they always get them.

Today, the McBurney Disability Resource Center holds a crucial and appreciated role in securing such access for students with disabilities, however, McBurney only addresses a handful of the issues faced by disabled students, staff and faculty on campus.

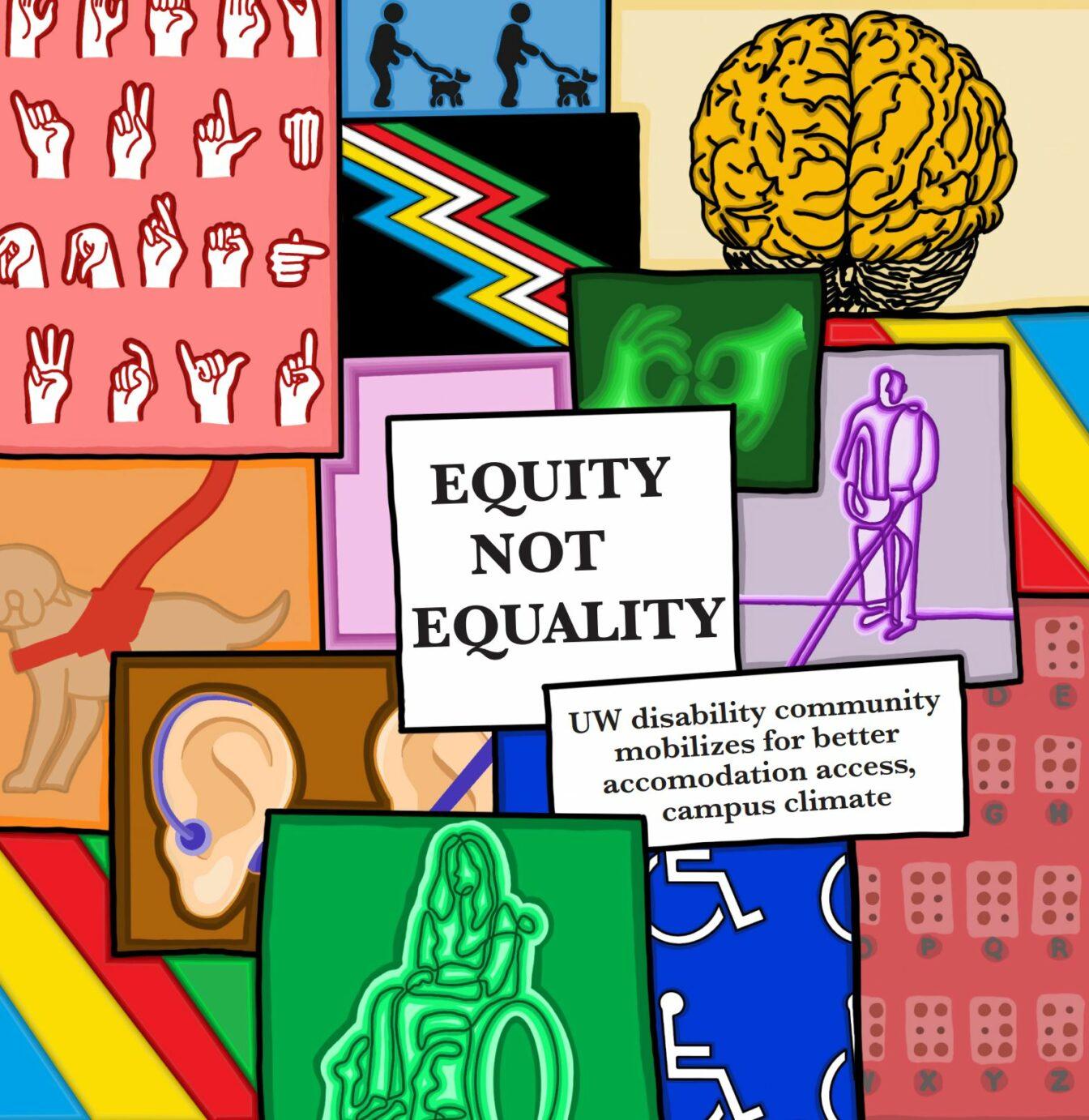

Following the footsteps of McGuire and the Capitol Crawl protesters, UW students and employees in the disabled community are continuing the fight for further recognition and inclusion on campus — for not just equality, but equity.

McBurney 101

Where other students are banned from using laptops in classes or certain elevators on campus, UW senior Justin Myrah has access thanks to the McBurney Center. Myrah, who has hemiplegic cerebral palsy, can use a laptop to take notes even if instructors have policies against technology and can use elevators otherwise closed to the student body.

Students themselves are the ones who know their access needs best, but the McBurney Center is the main avenue to adequately meet those needs through university-provided accommodations.

“I basically just told [McBurney] everything that I needed, and they were like ‘okay,’” Myrah said. “They even made more suggestions for me … [things] that hadn’t even crossed my mind.”

According to its website, the McBurney Center serves approximately 4,000 students who have been determined eligible for accommodations. These accommodations range from extra testing time and flexible deadlines to having an accessible shower in residence halls.

McBurney Center Director Mari Magler assures that any student who thinks they may be in need of extra support in the classroom may apply for McBurney’s services. A common misconception is that one must have an official diagnosis before applying for accommodations.

After submitting an accommodation application, students meet with an assigned access consultant who evaluates how to make the educational or housing environment most accessible for them. Magler said the initial meeting is the most important as it is when the McBurney Center gets to know the student in general, in addition to what barriers exist for them on campus.

“Disability is not a fault that lies with us individually. It is a thing that exists because of how the environment is created,” Magler said. “Let’s focus on the environment and not the person, if we can.”

Once a student has been approved for accommodations, they can go into their McBurney Connect online portal each semester and choose which accommodations they would like for each class, so they can tailor their accommodations to meet the specific demands of different courses, Magler said.

After selecting class accommodations, the portal generates a Faculty Notification Letter, which is sent to instructors at the beginning of the semester. Students are encouraged to meet with each of their instructors to discuss everything as well.

In addition to academics, the McBurney Center works directly with University Housing to ensure students are receiving necessary accommodations pertaining to daily living, Magler said. Similar to classroom accommodations, access consultants determine what housing accommodations are needed and then pass along requests to University Housing.

But, ease of access to accommodations is not equal for all students seeking them, as administrative barriers and actual adoption by instructors create more hoops to jump through.

Beyond undergrad

UW graduate student Amy is one of many who finds herself in a complicated gray area created by the decentralized nature of accommodations across campus.

UW employees work with an assigned disability representative inside their respective school or college to determine appropriate and necessary accommodations, Magler said. The Employee Disability Resource office, also known as EDR, supports these disability representatives in securing those accommodations.

But graduate students must work with both the McBurney Center and EDR to fully ensure an accessible experience at UW, and it can be difficult to know where to go.

“[Grad students] play a lot of roles on campus, and I think it can be harder to navigate those roles when you have a disability,” Amy said.

Amy said a unique issue facing graduate students is lack of formal medical leave policy. She is currently part of a student working group called Making Accessible Policies, also known as MAP, to address this, while also trying to make accessibility discussions more transparent in graduate handbooks.

UW sociology graduate student and teaching assistant Sara Trongone has an autoimmune disease and takes medication that makes her immunocompromised. Prior to the pandemic, she said she didn’t have any issues with asking for time off for transfusion appointments. But COVID-19 has changed the scope of her access needs.

Due to her immunocompromised status and uncertainty of whether she was producing enough COVID-19 antibodies, Trongone wanted to teach remotely for the fall 2021 semester. But after conversations with her disability representative and friends who were being denied or ignored, she felt discouraged from pursuing an official request.

“When I talked to a [representative] from the disability and accommodations office for the university, they just sort of said, ‘No one is getting accommodations,’” Trongone said. “At this point the university’s made it pretty clear … that what makes the university money is satisfied students, and most students seem to want to be in a classroom [to be satisfied].”

Trongone is not the only UW employee who felt discouraged at the start of the academic year as faculty members and others questioned some of the accommodations denied last semester. Thirty-one faculty members submitted accommodation requests, but only half of them were approved and one-third were still being processed less than a week before classes started. In the aftermath of fall’s accommodation conundrum, some campus community members are still uncertain what the university’s policy was and how decisions regarding remote learning were being made.

Magler said remote learning has been a popular accommodation request for both students and faculty since the start of the pandemic. The process for students requesting remote learning is the same as other accommodations, but it does require more documentation to fully understand the barriers presented by in-person instruction.

For faculty, course modality is set by individual departments based on what modality will fit effectively with the course, according to UW spokesperson Meredith McGlone. Faculty accommodations, COVID-19-related and not, are determined and approved on an individual basis.

“Where there are opportunities to match instructors looking to teach remotely with courses that are being offered remotely, we do that,” McGlone said.

Though Chancellor Rebecca Blank and Provost Karl Scholz denied both a blanket policy on remote teaching and claims of discouragement, 10 of 36 requests made as of Sept. 22 were withdrawn, one was denied and 14 were partially met, according to a report from Office of Strategic Consulting.

Even without a pandemic, many individuals still face a vast bureaucracy if they encounter challenges with their accommodations.

‘Three credit course’ to get accommodations

While the McBurney Center often successfully approves students’ appropriate and documented accommodations, the rest of campus is not always on the same page.

UW sophomore Priyanka Guptasarma said she sometimes spends a lot of energy just communicating how to work out her accommodations with instructors, particularly in her STEM classes.

For students, there are generally two grounds for which an instructor can deny accommodations. One is called a “fundamental alteration,” or when an accommodation would change the very nature of the class. In this case, Magler said the McBurney Center will work with the student, professor, department or academic advisor to either find an alternate class or work out an alternate accommodation.

The other is “undue burden,” which usually arises in the form of too high of a cost to implement an accommodation, but Magler said this is a relatively rare occurrence.

Otherwise, accommodations are protected by federal, state and university policy, and instructors must implement them according to the Faculty Notification Letter. Students are not obligated to share a disability status, which could subject them to unwarranted medical questions or stigmatization.

UW sophomore Brelynn Bille stressed that students, particularly those with invisible disabilities, should not feel pressured to disclose anything besides their accommodations.

“[Sometimes] professors go way too far in terms of making students almost justify their accommodations, and they have absolutely no right to be doing that,” Bille said. “There’s definitely a huge disconnect with professors at times with what is and isn’t appropriate for them to be doing when they receive our Faculty Notification Letters.”

Should a student face challenges with a professor, Magler said they should get in touch with their McBurney access consultant. There is also a grievance policy and bias incident report form students can fill out to address the issue.

Myrah, Bille and Guptasarma said they believe faculty could use more training on how to both implement accommodations in their specific classes and interact with students who have accommodations — but proper access to accommodations is just the start of improving disability inclusion on campus.

Redefining access and inclusion

When Magler worked for University of Minnesota’s disability office, she remembers a conversation with a blind student who said to her, “I might have the total access I need in class, but if nobody comes and sits by me and asks me how my weekend was or asks me to lunch, I don’t have inclusion.”

UW students and staff echo that sentiment — in order for disabled people to be fully welcomed on campus, the campus has to reshape how it thinks about access and disability more broadly.

In her ideal world, Bille said access means a complete elimination of physical and social barriers while awarding students with disabilities the exact same freedoms as nondisabled people.

“There are so many lecture halls where you are stuck either in the first row or the absolute back row if you have any sort of mobility contingencies,” Bille said. “If I need to use my wheelchair I should [not have to be] constrained to the front row or the back row.”

While the world is unlikely to adjust itself in a way that makes disability entirely obsolete, there are routes toward acceptance and normalization of disabilities as a part of life.

Myrah knows that not every person is going to want to discuss their individual disability and accommodations, and deciding whether or not to disclose a disability is a right. But he also believes having more open conversations about disabilities in general can minimize the stigmatization and othering of disability as a rare and personal phenomenon.

Many hoped the pandemic and the adjustments made during it would expand people’s understanding of accommodations and access. But Trongone said it unfortunately seems like the pandemic is being treated as an inconvenience society needs to overcome rather than an opportunity to learn how to be flexible and accommodating to people with all types of different access needs.

Amid a largely unmoving general public, the UW Disability Studies Initiative is one push in the right direction for changing the landscape of disability conversations on campus. UW Gender and Women’s Studies professor Sami Schalk said the initiative started about 10 years ago as a way to incorporate the field into UW academics.

While it is not a separate department or offered as a certificate, the main goal of the initiative was to hire faculty who incorporate disability studies into their field. Now, it is a collaboration which supports and highlights both campus events and professors who teach disability studies courses across various departments.

Go big or go bankrupt: Wisconsin farmers face daunting challenges as factory farms flourish

The initiative also brings in people from outside UW to give lectures or conduct workshops on disability studies-related subjects, Schalk said.

Though there is value in curricula within rehab psychology and special education that teaches people how to support the disabled community, Schalk said disability studies offers a more expansive method of learning about disability.

“Disability studies is a justice-based and often humanities-based approach to studying disability as a social and political issue rather than a medical issue based in somebody’s body or mind,” Schalk explained.

Schalk said disability studies offer insights into how ableism acts as a system of oppression, how disabled people have contributed to the world and understanding the rich culture and history of the community.

Finding community and culture

When freshman Emmett Lockwood first stepped onto campus this past fall, he was excited to find a hub for queer students — the Gender and Sexuality Campus Center, also known as the GSCC, which serves as a way for many LGBTQ+ affiliates and organizations to connect with each other. His next question — whether there was a similar entity for the disability community.

Though there is not currently a centralized space for disabled students to be directed to when seeking kinship, members of the community have still found ways to offer solace among each other.

Advocates for Diverse Abilities, or ADA Badgers, is a student organization for students with disabilities and allies to come together to engage in raising awareness on disability-related issues, listen to guest speakers and support each other.

People of UW: F.H. King farm director explains importance of gardening on UW campus

Bille, as the vice president of ADA Badgers, emphasizes how the organization provides a safe place for students with disabilities to share and empathize with each other’s experiences.

“We definitely have just had meetings where it’s a vent session [and] we talk about frustrations we might have about accessibility on campus or complications people have had with McBurney accommodations,” Bille said.

Guptasarma, who is the Vice-President of Advocacy and Education of ADA Badgers, said it helps to have guidance from fellow students to learn how to navigate the accommodations process.

Similarly, Amy founded the organization BadgerSTART as a way for all UW students to find connections with each other and advocate for issues facing the community. She is hoping to rebrand BadgerSTART to be a part of a national organization called Disability Rights, Education, Activism and Mentoring, known as DREAM. This would maintain the support network for disabled UW students and expand their advocacy efforts but also connect them with other DREAM chapters across the country.

Other ways students with disabilities have found ways to connect are specialized groups such as Chronic Health Allies Mentorship Program, also called CHAMP, Law Students with Disabilities Coalition and Disability Advocacy Coalition in Medicine.

These organizations sprinkled across campus undoubtedly serve a valuable purpose and show the resiliency disabled people have in building connections among one another. But Lockwood and others point to an issue of mainstream lack of recognition of disabled identity, which creates challenges in fostering a cohesive community.

This collective desire for mainstream identity-based inclusion led Lockwood to use his internship with ASM to start coalition-building and create a Disabled Students Cultural Center, or the DSCC. After garnering support from clubs, the McBurney Center and fellow students, he is currently in the process of gaining approval from Associate Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs Gabe Javier to start the DSCC.

Lockwood envisions the DSCC functioning like the GSCC by bringing awareness to student organizations with shared goals, creating space for meetings, providing formal and informal mentorship and connecting students with resources, including the McBurney Center.

“Once you get disabled people in a room together, once disabled people start talking to each other, so many more ideas about how the university could do better arise,” Lockwood said.

Lockwood also believes the DSCC can bring more visibility and recognition of disability culture and community to campus, and having a physical space beyond an accommodations office would help solidify the disability community as a valid identity group with a voice in campus decisions.

This visibility would ideally encourage conversations about accessible education and celebrate disability identity and all the community has to offer.

“Disability culture, from what I’ve seen, is always about meeting the other person where they’re at [and] making sure that you’re doing the best you can to be accessible,” Lockwood said. “It’s about accommodating each other and holding space for each other, but also finding joy in the aspects of us that many other people don’t know how to find joy in.”

Editor’s Note: This article has been updated to remove a last name at the request of the source.