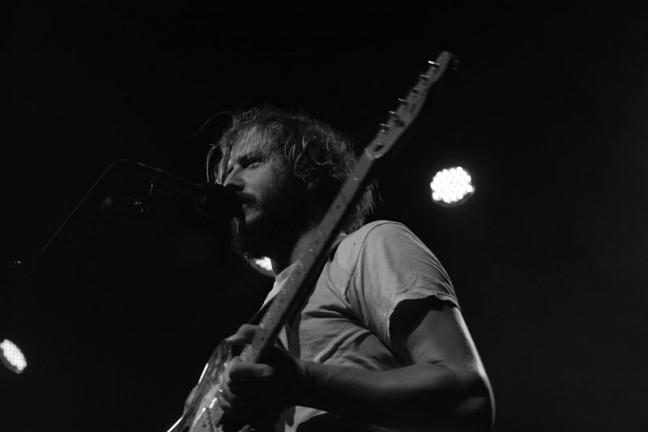

Eight years ago Justin Vernon and his band recorded much of For Emma, Forever Ago in a northwestern Wisconsin cabin. Bon Iver was propelled into stardom upon its release, but even as “Skinny Love” gently nestled into every indie-rock playlist, Vernon’s hometown of Eau Claire, Wisconsin remained his creative foundation.

This summer Vernon — in collaboration with producer and guitarist for The National Aaron Dessner — will share Eau Claire’s artistic prowess through an aptly-named music festival of their own creation: Eaux Claires. In addition to Bon Iver, headliners like The National, Spoon, Sylvan Esso, Sufjan Stevens and Indigo Girls will grace its stages July 17 and 18.

Though Vernon dreamt of filling the Chippewa River Valley with festivalgoers for many years, he could not do so alone. Roughly two years ago he approached Michael Brown — famed production designer for Vernon and The National — to help create an experience unlike that of any other festival.

“Some [festivals] are these amazing little pockets of culture that benefit all the people around and some are these terrible experiences,” Brown said. “In a lot of ways we wanted our own opportunity to make a statement and give our own attempt at one.”

Brown swiftly became Eaux Claires’ creative director, dedicated to bringing to life the vision he and Vernon shared. Since its original conception, the pair have sought to elicit a sense of community, Brown said. For Vernon, there is only one place where this could be achieved: Eau Claire.

“It’s been important to Justin throughout his entire career to try and bring focus back into Eau Claire, and that’s been one of the reasons he never really left Eau Claire; he’s chosen to make his roots here specifically so he can help bolster the community,” Brown said.

Vernon’s sentimentality is not the only thing that makes Eau Claire ideal for a music festival. In fact, Country Jam and Blue Ox have already made the Wisconsin town their home for several years. It has sizable parks available for large scale events (including campgrounds), significant student presence courtesy of its UW System campus and a convenient location between Madison and the Twin Cities. Last but not least, Eau Claire has developed a substantial and, perhaps even more importantly, inclusive music scene.

“We definitely didn’t want to create a festival that could have been just pigeonholed as ‘this is just the folk music festival,’ or ‘this is the rock music festival,’ or even ‘this is the indie rock festival.’ That is one thing that Justin is definitely striving to do, is make sure this is an event that … is musical education,” Brown said.

This “music education” occurring between audience and artist manifests in the sense of community Eaux Claires hopes to foster. The concept was a primary factor in every step of Eaux Claires’ development, from booking acts to mapping the grounds. Vernon specifically catered the lineup to create a holistic experience. Audiences are intended to enjoy all acts with their fellow concertgoers, Brown said.

Unlike other festivals housed by one generally large area, attendees are encouraged to travel between Eaux Claires’ two stages via a wooded path, Brown said. While serving as a music “palette cleanser” between acts, it also provides an avenue for interaction.

Festival planners also realize community is not synonymous with being pressed up against sweaty bodies all the time. Attendance will be limited to avoid people being bombarded by others and the attractions, Brown said.

Just as Eaux Claires seeks to push Chippewa River Valley’s physical boundaries, Brown and his team hope to push the boundaries of what a concert can be. Not only are patrons expected to foster community among themselves, but with the artists as well.

“There’s going to be a lot of alternate performances in different kinds of performance spaces, to give you an idea of the regular relationship between the stage and the audience, and really trying to alter that,” Vernon said in an interview with Billboard. “We’re trying to be unique at a global scale, colliding art forms and music and collaborations between artists of all kinds together.”

For Brown, facilitating the “relationship between the stage and the audience” was both the biggest challenge — and biggest reward — of working on the festival. While he is accustomed to working with lighting, scenery and other visual elements as a production designer, creating a large-scale exposition capable of connecting with patrons on a new level posed unique obstacles.

“[We considered] how do we take that traditional environment that everybody knows with audience versus stage, and how can we completely alter that?” Brown said.

Versatility and experience were key in manufacturing stages that would be fluid enough to gratify artists and audiences, Brown said.

When the lights dim the final performances, Eaux Claires’ creators hope attendees will leave with more memories than sunburns and hangovers.

“What would be a huge win in my opinion would be every artist and every attendee to comes to the festival in some way to have a personal experience,” Brown said. “The whole dream is for it to become more than just a music festival.”