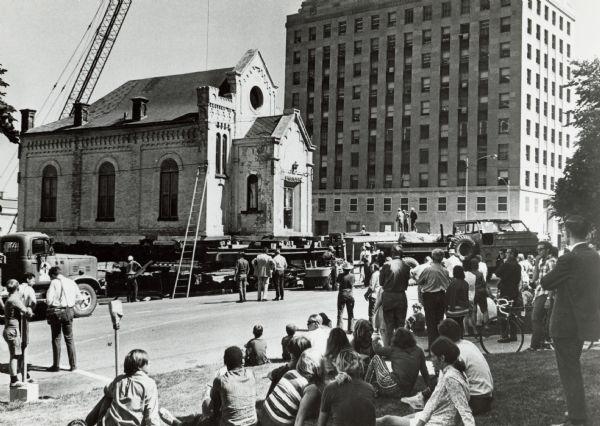

A crowd gathered near the Capitol July 19, 1971 as witnesses to Madison’s first ever transported-for-preservation building made its way from Washington Avenue to James Madison Park. Gates of Heaven Synagogue, now used as a voting location and various celebrations, went mobile for a day as it was thrown on wheels and saved from demolition.

The edifice was a creation of prominent local architect, August Kutzbock, known for his Reconstructionist style also seen in Pierce House, The Van Slyke House and the second Capitol building. The current Capitol is the third, so far.

It was originally constructed at 214 W. Washington in 1863 after a group of 17 Jewish families put together $4,000 to construct the first synagogue in the state of Wisconsin, according to the 1970 Register of Historic Places Nomination.

Close call at Gates of Heaven

Financial issues plagued the congregation and during the panic of 1887 they leased the building and in 1916 sold the building. Its subsequent string of occupants included a Unitarian Society, the Women’s Temperance Union, a Lutheran church, an undertaking parlor, a temporary recording studio, a tea room, federal storage, a veterinary clinic, offices, a beauty shop and a dentist office. Finally, showing its age in 1970, the building sat vacant, and along with the rest of the block, was slated for demolition.

The synagogue was largely constructed using sandstone from a local quarry, historian Dick Wagner said. In fact, during the era of the synagogue’s construction, Madison experienced a “golden age” of architecture with a multitude of German and Swiss masons building many of the houses that sit around the Capitol. Kutzbock used the distinctive Madisonian sandstone on the Peirce House and many of his creations adorning the Mansion Hill district.

The news that the historic building was to be torn down pulled at the heartstrings of many historians and members of the Jewish community, and community members felt an approaching threat from an “attitude of commercial institutions,” which would endanger landmark sites, according to a news report from 1970 from Wisconsin Historical Society’s archives.

“… the decision to demolish the Old Synagogue was apparently made in silence and permitted by city officials in the most hushed of legal tones,” according to the news report.

A task force was assembled including Norton Stoler, leading the grass roots fundraising, and other city officials including Mayor William Dyke, Sol Levin from the Housing and Community Development Department and other representatives.

Critics of the plan to move the synagogue argued James Madison had been “carefully and laboriously carved out,” Wagner said. He said many residences were displaced to construct the park and it would not have been suitable to leave an abandoned synagogue in disrepair unless renovation occurred. Wagner helped secure grants to renovate the interior and bring electricity into the building.

It was in the eleventh hour that the synagogue was added to the list of historic buildings and the funding for its trip across the square was secured. By the time it was going to be moved, Gigi Holland, volunteer and memorabilia coordinator, described the scene as comical.

“A massive construction pit with the synagogue standing in solidarity, the only building on the block,” Holland said.

The synagogue was not the first building in the city to be moved. Wagner said the practice was common when Capitol-area houses were relocated to the Basset Street area. He went on, however, to say it was, “the first building in the city that was moved for historical preservation purposes.”

Synagogue on the road to safety

The synagogue stood for more than the Jewish community in Madison; its brush with demolishment came shortly after the Mapleside building on University Ave. was torn down despite much opposition in an event Wagner described as nothing short of traumatic.

Holland ascribed the proposed demolition not to apathy, but described how there was a lack of precedent for relocating buildings for preservation. The synagogue was a turning point, a success that would go on to inspire a tradition of preserving the history built up throughout Madison, she said.

On the day the building was moved, the construction worker placed a bottle of champagne in the vestibule. For a day, Gates of Heaven went mobile as it was transported up West Washington Avenue toward the Capitol on the square, “ducking wires and poles along the way,” Wagner said.

“Hundreds of onlookers watched its progress while Madison police provided a safety escort,” Small Synagogues’ website said.

A crowd of 200 cheered as the synagogue was moved to its new home in James Madison Park July 17, 1971. The one-mile transport took seven hours.

Champagne safe and awaiting consumption, workers celebrated the saved synagogue. Then began the building and site restoration.

The friends of the Gates of Heaven formed as a group dedicated to replanting and beautifying the area of the park that had played host to the massive flat-beds that brought the old sandstone gathering place to its new location. Holland, a long time member who still volunteers with the landscaping, said the group is entirely self-funded and purchased the memorabilia stand, the walkway and the bronze plaque commemorating the 40th anniversary of the building’s salvation.