Nurse Justin Giebel held up a phone for a dying patient. On the other line was a son and daughter, speaking to their parent for the last time. The elderly patient was a no-code, meaning if their heart stopped, no resuscitation measures would be taken. Once the patient’s health declined, their family had limited time to say their goodbyes.

The pandemic’s no-visitor policies forced the patient’s family to grieve without saying goodbye in person — and forced an immense burden on Giebel he wasn’t prepared to bear.

Giebel graduated from the University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire in 2019 and was hired at UW Health for his first nursing job only months before the COVID-19 pandemic. Surrounded by severely ill patients, unprecedented amounts of death and grieving families, Giebel found himself working in an environment where wins were “hard to come by.”

This environment is far from the picture of saving lives and giving compassionate care Giebel pictured. When he started as a nurse, Giebel was inspired by the field and the prospects to grow his skills to help others. But the destruction of the pandemic has disillusioned Giebel’s outlook — especially as he observed the treatment of nurses. He has even doubted his ability to continue as a nurse.

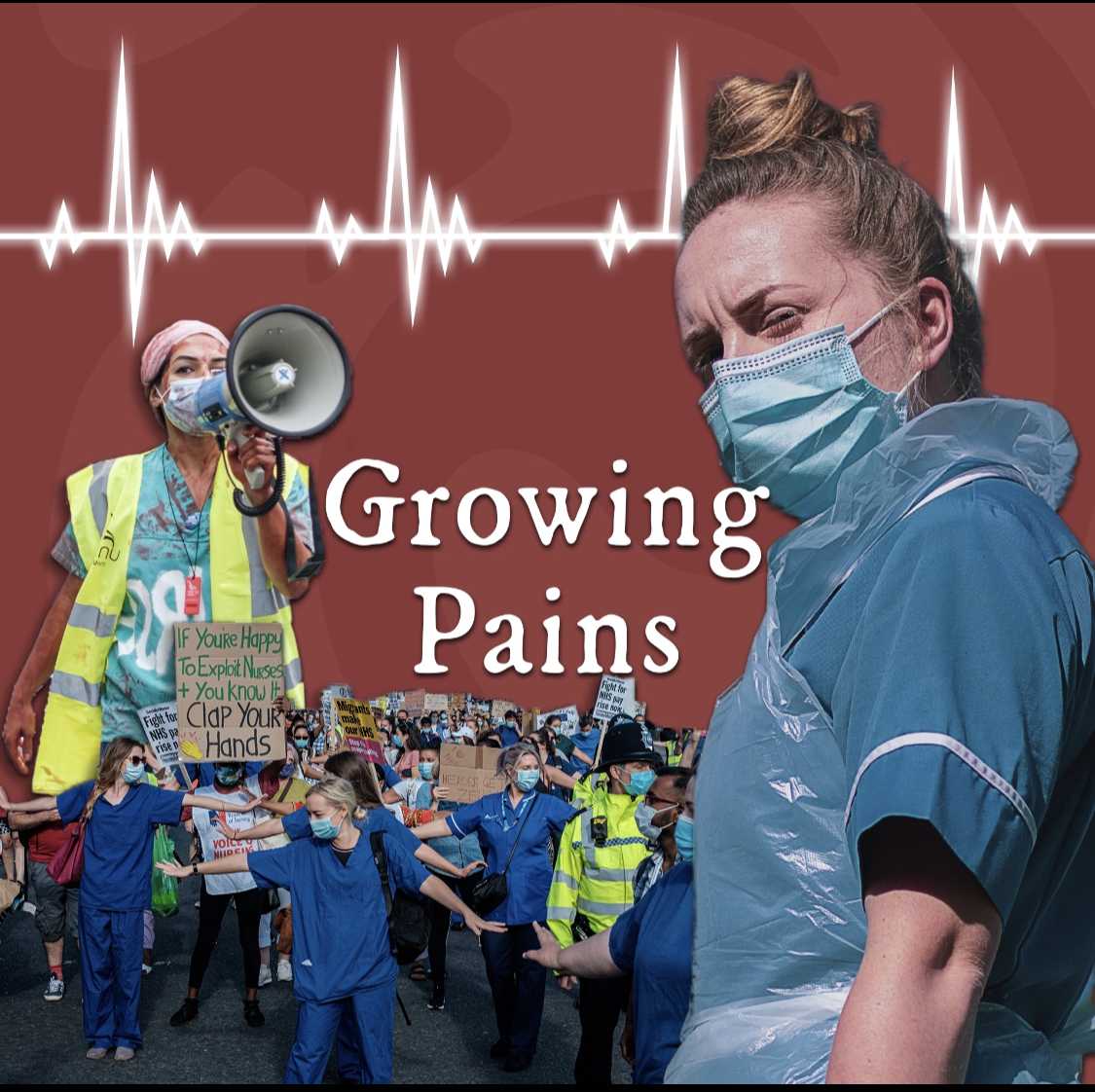

The pandemic is not the only factor taking a mental toll on nurses in Madison. A national nursing shortage has led to short-staffing as well as increased mental and physical exhaustion. At the mercy of these harsh conditions, UW Health nurses have continued to fight for unionization to no avail.

With the pandemic only fueling the fire, conditions are coming to a head and nurses are demanding change. As current nursing students are forced to reconcile how the future of nursing may look, many young and veteran nurses are still determined to persevere into uncharted water in hopes of driving cultural changes in the field.

Failure to meet growing demand

Between the aging baby boomer generation’s increasing healthcare needs and an influx of patients in hospitals due to COVID-19, the demand for nurses is rising exponentially across the country. Nurses are often scrambling to meet patients’ needs while working long, arduous hours without sufficient resources or support.

Giebel was barely out of school when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, rattling him and his peers.

Giebel began his career in an intermediate care unit, which was a high-stress environment despite patients being “healthier” than those in an intensive care unit. The next step for many of these intermediate care COVID-19 patients was a ventilator — a mentally taxing reality for the nurses who knew that this significantly reduced chances of survival.

Even for experienced ICU nurses who were used to taking care of the most gravely ill patients, COVID-19 had unprecedented effects.

Amanda Klinge, a nurse at UW Health for five years, said the physical and mental health struggles nurses are facing existed long before COVID-19 and were exacerbated by the pandemic — including the particularly exhausting plight of short-staffing.

A 2018 study predicted a shortage of 154,000 registered nurses by 2020 and over 500,000 by 2030. In Wisconsin alone, it is projected by 2035 there will be a deficit of 20,000 nurses.

“[Doctors] can do all of the exciting work, but if you don’t have a nurse to take care of that patient afterwards, my guess is that your outcomes are going to be really poor,” Giebel said.

The burden of serving an increasing retired and aging population is another substantial factor contributing to nursing shortages. According to the National Council of Aging, 85% of older adults have a chronic disease and 60% have more than one. Addressing these concerns in the baby-boomer generation of 71.6 million people is a daunting task considering the number of RNs in the United States is currently 3.8 million.

Building on the existing nationwide nurse shortage, COVID-19 led to an influx of nurses leaving the profession all together. The pandemic left some nurses unable to work due to severe complications from COVID-19 while others were traumatized by their experiences and chose to leave the field. Vaccine mandates also led to the departure of thousands of nurses, either from layoffs or resignations.

Though the demand for nurses is projected to grow significantly in the next decade, data from the American Association of Colleges of Nursing suggests the moderate rise in enrollment of nursing students will not make up for the 1 million RNs preparing to retire in the next decade, especially as the pandemic hastens nurses’ exits from the field.

The result of an influx of patients and fewer nurses available to care for them — nationwide staff shortages, which often require nurses to take on additional workloads and extra shifts, threatening to burn out those in an already taxing profession.

Dangerously short-handed

Many hospitals are already operating short-staffed — with dangerous consequences for both nurses and patients.

Giebel said short-staffing can result in an overwhelming amount of additional responsibilities during long nursing shifts in the face of a constant barrage of requests to pick up extra shifts. Walking into a shift after seeing those requests all day, Giebel knows he’s about to work with three, four or even five nurses fewer than a full staff.

“It’s exhausting for all of us working. And then it’s exhausting on our days off to be inundated with texts like ‘This unit is short today, and this unit is short too,’” Klinge said. “Even when you’re not at work, you feel guilty, and it just takes a mental toll.”

For many of Klinge and Giebel’s peers, this toll has created new mental health problems, including anxiety and depression. Nurses are also more likely to be physically injured as they try to care for patients while short-staffed, Klinge said.

PTSD in particular is a concerning diagnosis for nurses. A 2021 study found working in the emergency department of a hospital during COVID-19 and picking up irregular shifts led to an increased risk of PTSD diagnosis. With symptoms including emotional avoidance, worsened cognition, mood alterations and sleep disturbances, PTSD can greatly interfere with a nurse’s work.

“A lot of my colleagues have newly diagnosed mental health problems requiring medication or leaves of absence or leaving bedside nursing altogether,” Giebel said. “And I know from my experience I’ve definitely struggled with bouts of some pretty depressive feelings and stress and anxiety, probably bordering on PTSD.”

Short staffing has devastating impacts not only on nurses’ well-being but on patient safety as well. Under these conditions, Klinge said patients are more likely to fall, get a hospital-acquired infection, have medication errors and experience other adverse events.

When short-staffed, Giebel said charge nurses will often take on patient assignments. Charge nurses are responsible for coordinating patient care and keeping track of patients moving within or across hospital units, acting as a sort of shift lead for the bedside nurses. Adding patient assignments to their workload only places an extra burden on them, making it more difficult to reach when other nurses need to consult with the charge nurse.

When charge nurses aren’t available, Giebel said nurses must double up on patients and take on a “less-sick” patient in addition to a severely sick patient who should be one-on-one with a nurse.

Giebel cited a study that found for every additional patient a nurse takes on, the patients’ likelihood of dying within 30 days of hospital admission increases by 7%. High patient loads are also associated with increased surgical site infection and higher hospital readmission rates.

Giebel said nurses are aware of the statistics and know as their patient load increases they are more likely to make mistakes or miss something. For nurses who strive every day to give high-quality care, knowing it is physically impossible for them to do so is extremely distressing.

“None of us got into nursing to give half-hearted care, and when that’s all we can do to get by, it’s really hard for us to accept,” Giebel said.

Though nurses are problem-solvers by nature, they are suffering due to shortages and their adaptability is not enough to address these challenges. UW Health has taken some action to improve conditions, however, some nurses feel these attempts are lacking.

‘No teeth’: The push for a union

Some nurses are dissatisfied with the measures UW Health has taken to address the pitfalls of short-staffing. Other nurses feel unheard, saying their calls for better working conditions have been largely ignored or unmet entirely.

At a culmination of these frustrations on Feb. 24, hundreds of nurses and community members gathered across the street from UW Health’s main campus. Braving freezing temperatures and snowfall, they waved signs and elicited honks of support from drivers. The demonstration, formally named the “Informational Picket for Safe Staffing, Quality Care, and a Union,” is only the most recent example of a long, hard-fought push for unionization at UW Health — and nurses are far from giving up.

Pat Raes, a nurse at UnityPoint Meriter Hospital for the last 30 years and president of the SEIU Healthcare Wisconsin union, has seen the struggles UW Health nurses are dealing with firsthand.

“They [UW Health nurses] have often told me it feels like they have ‘no teeth,’ because even though things are discussed between the two groups, management has often not changed their opinion from what they came into the meeting with,” Raes said. “It doesn’t improve things for the nurses or the patients.”

Klinge said working conditions, along with the fact UW Health decreased their starting pay for nurses this year, has made UW Health less competitive against other hospitals and is driving new nurses to seek employment elsewhere.

“We [UW Health] offer compensation in nursing that compares very favorably to our peer organizations,” UW Health Press Secretary Emily Kumlien said in a statement. “To ensure we stay competitive and aligned with the market, we regularly assess our total compensation and make adjustments where they are necessary.”

One such competitor, also located in Madison, is UnityPoint Health Meriter Hospital. Raes said Meriter has also struggled with nursing shortages, however, in contrast to UW Health, nurses at Meriter have a different avenue to raise their concerns — a union.

SEIU Healthcare Wisconsin is the largest healthcare union in the state and has been working with Meriter since the 1970s. Raes said the union allows nurses to bring up issues to hospital management and to have their concerns genuinely heard.

Compared to the existing UW Health nursing councils with limited bargaining power, Raes said she believes unions give nurses a stronger voice, as representatives amplify the voices of hundreds or even thousands of members. The negotiation of contracts between the union and the hospital also ensures nurses have protection to bring up concerns without fear of retaliation.

With the help of their union contract, Meriter nurses were able to bargain for an additional 60 hours of time off since many nurses had used up their time due to having or being exposed to COVID-19. They were also able to negotiate a retention bonus for new nurses, vetted proposed furniture that was not safe for physically unsteady patients and won the right to have a voice in future healthcare emergencies.

“We know that even though it doesn’t feel like we’re getting anywhere sometimes, right at that time, we know it’s applying pressure and so down the road, we’ll get something that we had been pushing for,” Raes said.

UW Health nurses are no strangers to working with SEIU. Up until 2014, UW Health was also represented by SEIU before Act 10 removed UW Health’s obligation to recognize their union membership. The goal of Act 10 was to address a budget deficit of over $3 billion by reducing the state’s financial contribution to government employees.

This included requiring employees to increase their pension and health insurance contributions. The act also reduced the collective bargaining rights of most public employees and repealed the law requiring UW Health to engage in collective bargaining.

In May of 2021, the Wisconsin Legislative Council released a memorandum outlining the effects of Act 10 on UW Health’s right to union negotiations. According to the memorandum, UW Health is not allowed to formally or voluntarily recognize a union for collective bargaining, however, UW Health could “meet and consult” with a union representing its employees.

These meetings would not enact the collective bargaining that UW Health is prohibited from and would open the floor for discussions with a union, but the union could not take any official action to enforce agreements.

According to a press release from SEIU, the memorandum concluded UW Health could voluntarily recognize the nurses’ union and bargain a contract. According to SEIU, the Wisconsin Legislative Council stated Act 10 only removed the obligation to do so.

UW Health, on the other hand, has maintained they are prohibited from recognizing the union and participating in any discussions with a union.

“While the law is clear that we cannot recognize a union and collectively bargain a contract, we will continue working directly with our nurses through our nursing councils to address workforce challenges and continue improving the patient care we provide,” Kumlien said.

To address nurses concerns, Kumlien said UW Health has hired over 300 nurses in the past two years and has retention rates much higher than the national average.

Due to increased demands, there is still a need to hire more nurses and more clinical staff in general but Kumlien said UW Health is also working on recruitment and retention campaigns to address staffing needs.

“The stress, burnout and moral distress experienced by our nurses, our physicians and all of our clinical staff is very real,” Kumlien said. “We offer many resources to help our employees process and work through the strain and have created new tools like our Nursing Wellbeing Council to help develop and drive new solutions.”

Despite the recent changes, Klinge said the fight for union representation at UW Health has been “a long time coming.” In February 2020, just weeks before the pandemic hit, the University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics Authority board voted against voluntarily recognizing the union. Since then, Klinge said conditions have only gotten worse and the movement has only grown stronger.

The nurses’ union has also been endorsed by the Dane County Board of Supervisors as well as some Madison City Council alderpersons. Gov. Tony Evers also expressed support for the nurses’ union at a virtual forum.

“We have support from other people in the community now, and we have support from some political allies,” Klinge said. “We are pushing forward because we want to see our patients have better outcomes, have safe staffing and a better experience at UW.”

A large amount of support has also come from the UW nurses themselves. According to the SEIU press release, 1,500 UW Health nurses have signed cards in support of the union, which were then presented to University of Wisconsin Health and Clinics Authority CEO Alan Kaplan Jan. 13.

“We’re just trying to spread the information and awareness and show that we are a union and we are organized and we’re not giving up,” Klinge said. “After the picket, we’ll keep moving forward, but we would like to see a vote happen in the near future”

Still, union representation will not be enough to address the staff shortages being felt by hospitals across the country, Klinge said. The nursing shortage is a systemic problem and will require systemic solutions.

Changing the culture

Giebel has always been drawn to healthcare and firmly believes he was meant to be a nurse, however, he was shaken by the unexpected challenges he faced amid the pandemic.

The working conditions due to staffing shortages caused Giebel to rethink the entire field of nursing. He has doubted his ability to continue being a nurse, weighing his passion for helping others against the harm to his personal well-being.

“Even before I started working in the ICU with these nurses, they had expressed, ‘These are the sickest patients we’ve ever taken care of — the most deaths we’ve ever seen,’” Giebel said. “Really hard things to hear and to know and to be one of my first experiences as a nurse.”

Despite hearing about the high levels of short staffing and burnout is daunting, first-year UW-Madison nursing student Maddie Donnelly said it has not deterred her from the profession. Donnelly was drawn to nursing as a way to help and connect with patients, which outweighs the challenges she knows she’ll face.

Donnelly is not alone. Even in the face of recent challenges prompting veteran nurses to leave the field, there are over 250,000 students currently enrolled in nursing programs across the country.

The UW-Madison School of Nursing has also been working to mitigate nursing shortages since 2018 through an accelerated Bachelor of Science in Nursing degree, also known as the BSN program. While enrollment percentages are consistently increasing, a statement from the UW School of Nursing warns interest in the nursing profession is not the issue when it comes to addressing nursing shortages.

“While the high levels of interest in nursing education might sound promising in terms of addressing the nursing workforce shortage, the barrier does not stem from a lack of prospective students; it lies in a critical shortage of nurse educators and available resources,” the School of Nursing statement said.

According to the School of Nursing statement, the solution to the nursing shortage cannot be unsustainable changes like overworking and increasing patient loads. The statement calls for “meaningful systemic and cultural change” to address the urgent issues at hand.

A more tangible outline of these systemic changes comes from a National Academy of Medicine report about the future of nursing. The report outlines a framework of nurse well-being and offers interventions on an individual and systemic level. According to the UW School of Nursing release, the report offers hope that national leaders are working to address the challenges nurses are facing.

As more nursing students graduate and choose where to work, the culture of the nursing profession is an important factor. When finding a workplace after graduation, Donnelly said whether nurses have a voice at the hospital will be an important factor in her decision. Nurses are the best advocates for their patients and themselves because of their ability to see the effects of large-scale decisions firsthand at the bedside, Donnelly said.

The future of nursing may be uncertain, but many nurses and experts agree current working conditions are not sustainable, with grave ramifications for nurses and patients. Whether solutions are found through unions, the “Future of Nursing” report or enrollment of more nursing students, change is imminent.

“I recognize the extreme need for nurses,” Donnelly said. “And although I know it will be challenging, I look forward to making a difference, no matter how small it may be in the grand scheme of things.”