Aug. 20 started with a torrential downpour. Caitlin Pueschner clocked in for her shift at the Whole Foods on University Avenue the same way she would on any work day.

But at around 8 p.m., a five-foot-tall swell of water grew so high it blocked the doors of the grocery store, trapping everyone inside. Only one woman made it outside in time to reach her car.

In a matter of minutes, the store turned dark. The power had shut off.

“Some of the employees were very frightened,” Pueschner said. “People [were] really nervous once the lights went out and when they’d bump into things underwater.”

Pueschner, her coworkers and customers all had to stand on top of desks until emergency personnel arrived to evacuate them.

Although Pueschner sustained no injuries, she was shaken by her experience.

“I was really scared to drive home. I was worried about getting stuck,” she said.

Whole Foods lost more than $200,000 of merchandise throughout the 90-minute flood. But it was only one of many victims of the unrelenting floods affecting the isthmus the past few weeks.

The flood not only devastated businesses like Whole Foods, it also made Lake Mendota more vulnerable to algae blooms, one pollution issue that has been plaguing the lake since the 1940s.

The most recent flood has increased runoff of phosphorus, a nutrient typically used as a crop fertilizer that encourages organism growth, from rainfall and nearby agricultural lands into the lake.

Something in the water

Although phosphorus runoff from rainfall encourages plant life in lakes by creating excess nutrients therein, it takes away oxygen animals may otherwise consume, causing death — a process called eutrophication, according to University of Wisconsin limnology professor Stephen Carpenter.

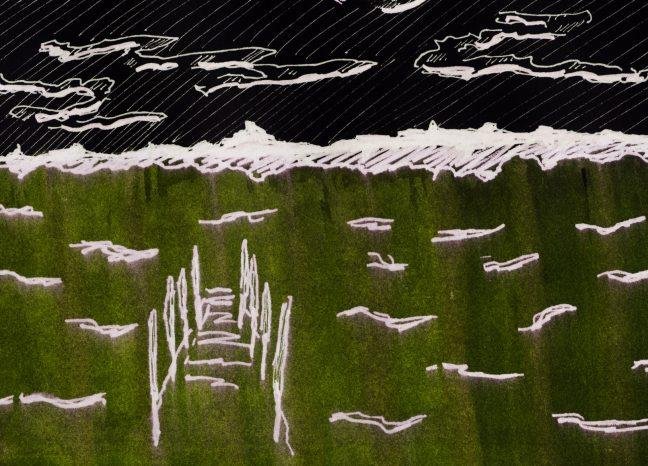

For instance, eutrophication manifested in June 2017 in the form of a toxic blue-green algae bloom that crept over the surface of Lake Mendota.

The algae bloom, cyanobacteria, can harm not only animals but also humans. It can, among other health issues, damage the liver and other internal organs, according to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. The severity of such pollution has forced many Madison-area lakes and beaches to shut down.

Worries about further water pollution in light of the flood have only encouraged individuals and organizations from UW and the Madison area in their work to resolve Lake Mendota’s persistent phosphorus problem.

Among these individuals is Dave Elsmo, sailing program manager and head coach of the Wisconsin Hoofers sailing club.

The sailing program loses money every time the high toxicity level in Lake Mendota cancels practice or causes it to move location. But Elsmo is also concerned about the impact of lake pollution for the greater Madison area, beyond the reaches of UW and his organization.

“The phosphorus and its associated outfall is pretty substantial to the community at large,” Elsmo said. “We’ve seen reports of dogs being killed by this stuff.”

Because the Memorial Union terrace is located on the shores of Lake Mendota, life on campus has been affected as well.

UW junior Tanner Bilstad, for instance, was disappointed that the pollution prevented him from enjoying a swim in the lake this past summer.

“This summer I would have loved to jump into the lake after running along the Lakeshore Path on the really hot days,” Bilstad said, “However, the potential harm from the blue green algae prevented me from doing that, and not being able to enjoy the water was a real bummer.”

Solutions in bloom

Determined to fight back, Elsmo has worked alongside UW’s Environmental Health Services Division to test Lake Mendota regularly for dangerous levels of algae contamination.

Elsmo said the university has used retention systems to manage stormwaters, which he hopes will reduce the amount of phosphorous entering the lake.

Elsmo’s organization, Wisconsin Hoofers, is trying to make a difference too. Starting Oct. 1, Hoofers will be undertaking a renovation project that will install several more water filtration and stormwater abatement systems, as well as make the lakefront more environmentally friendly.

“Right now it’s a concrete jungle,” Elsmo said. “One of the big things we integrated into the renovation is some green space on our lakefront.”

The plants in the new green space will help serve as a bioretention area that holds and filters a large amount of phosphorus-rich rainfall. He hopes the process will reduce the amount of phosphorus leaking into Lake Mendota, therefore decreasing incidents of toxic blue-green algae blooms and improving water quality.

Elsmo has faith the work Hoofers and UW is doing will pay off in the end.

“The university has a huge plan for [reducing pollution],” Elsmo said. “They’re thinking about it on a macro level.”

Outside of the university, non-profit organization Clean Lakes Alliance has also worked to help improve and protect bodies of water within the Yahara Rivershed area, including Lake Mendota.

Clean Lakes Alliance spokesperson Adam Sodersten said the organization has been using CLEAN, a 14-step action plan designed in 2012 to reduce phosphorus in lakes by 50 percent by 2025, to guide their effort in quelling pollution in Madison-area lakes.

“Our main goal is helping fund and implement lake improvement projects that reduce phosphorus, educating the public on how to change practices on the land to slow runoff, and to give the public [better] lake conditions,” Sodersten said.

Others are less confident about using phosphorus removal methods to alleviate pollution in Lake Mendota.

UW soil science professor Phillip Barak is one such person.

“We’re conservative about what the implications of phosphorus removal might be,” Barak said. “It might not make an appreciable difference in the phosphorus content of the effluent that is released back into the surface waters downstream of Madison.”

Circle of life

Still, Barak believes the technology he is currently developing, which could extract, recover and repurpose phosphorus into dry fertilizer, would make a positive impact to both lake water quality and farming fields because the same process that contaminates lake water also encourages plant growth.

This process, he said, underscores a mutually beneficial exchange of nutrients. The idea is to move from waste, to recovery, to food.

“If the phosphorus that goes to the wastewater treatment plant isn’t going out with the effluent water, then it has to go somewhere,” Barak said. “In the United States most of the [phosphorus] is applied to land, to agricultural fields. It serves as a nutrient source to the soil [and] to the plants.”

Because factories spend as much as $250,000 annually to unclog and remove phosphorus that would otherwise crystallize, Barak said he believes his technology will also contribute to a productive, ecological solution for an otherwise difficult, expensive and labor-intensive process.

Barak’s goal is to recover phosphorus by treating five to 10 percent of solids that go through wastewater treatment plants. This process would also reduce the amount of phosphorus being consistently released back into Madison-area lakes; others so far have focused mostly on cleaning rainfall as they come.

Too close for comfort

Although outside the path of Hurricane Florence, a storm currently devastating the Carolinas, Wisconsin is not immune to the effects of climate change, one of which is the increased level of phosphorus in the lakes surrounding Madison.

Despite efforts by many individuals and organizations in the Madison area, phosphorus inputs to Lake Mendota have remained relatively constant.

Murky waters: Foxconn deal brings economic opportunity, environmental concerns

The increase of hard surface areas such as roads and roofs, according to Carpenter, is one factor that offsets efforts to better manage phosphorus output from agricultural lands, as phosphorus runoff increases with the size of hard surface areas.

Artificial interruption to nature aside, Carpenter said warmer waters have also caused lakes to be more susceptible to harboring toxic algae blooms. In recent years, UW lake researcher John Magnuson has documented a steady decline in how long lakes in Wisconsin are staying frozen.

Lake Mendota has averaged six fewer days of ice cover every decade from 1956 to 2006, indicating not only warmer winter temperatures but a changing lake environment.

All this is symptomatic of what Carpenter considers the culprit of the continuous lake pollution Madison confronts: volatile, unpredictable environmental conditions.

“Precipitation is increasing and big storms are more frequent,”Carpenter said. “[Although] Dane County, municipal governments, Yahara Pride and other farmers are making strides toward reducing phosphorus pollution … there is still a lot of phosphorus in soils.”

As Hurricane Florence wreaks havoc on the East Coast, dropping upwards of 25 inches of rain in cities across the Carolinas, the repercussions of climate change are becoming increasingly evident. Flash floods, much like those Madison experienced at the end of August, are closing interstates and isolating cities, preventing aid from reaching citizens.

City of Madison engineer Robert Phillips warned that Lake Monona has reached 100-year flood levels; Lake Mendota is not far behind.

According to the Wisconsin Department of Emergency Management, floods between Aug. 17 and Sept. 3 are responsible for more than $39 million worth of damages to county and local governments alone.

While the floods have caused unprecedented damage, climate change trends reveal that severe weather and storms are only becoming more frequent.

Recent natural disasters in Madison have so far ravaged businesses and displaced citizens. Further damages, monetary and psychological, are not far out from the horizons of Lake Mendota — on which algae bloom already looms large.