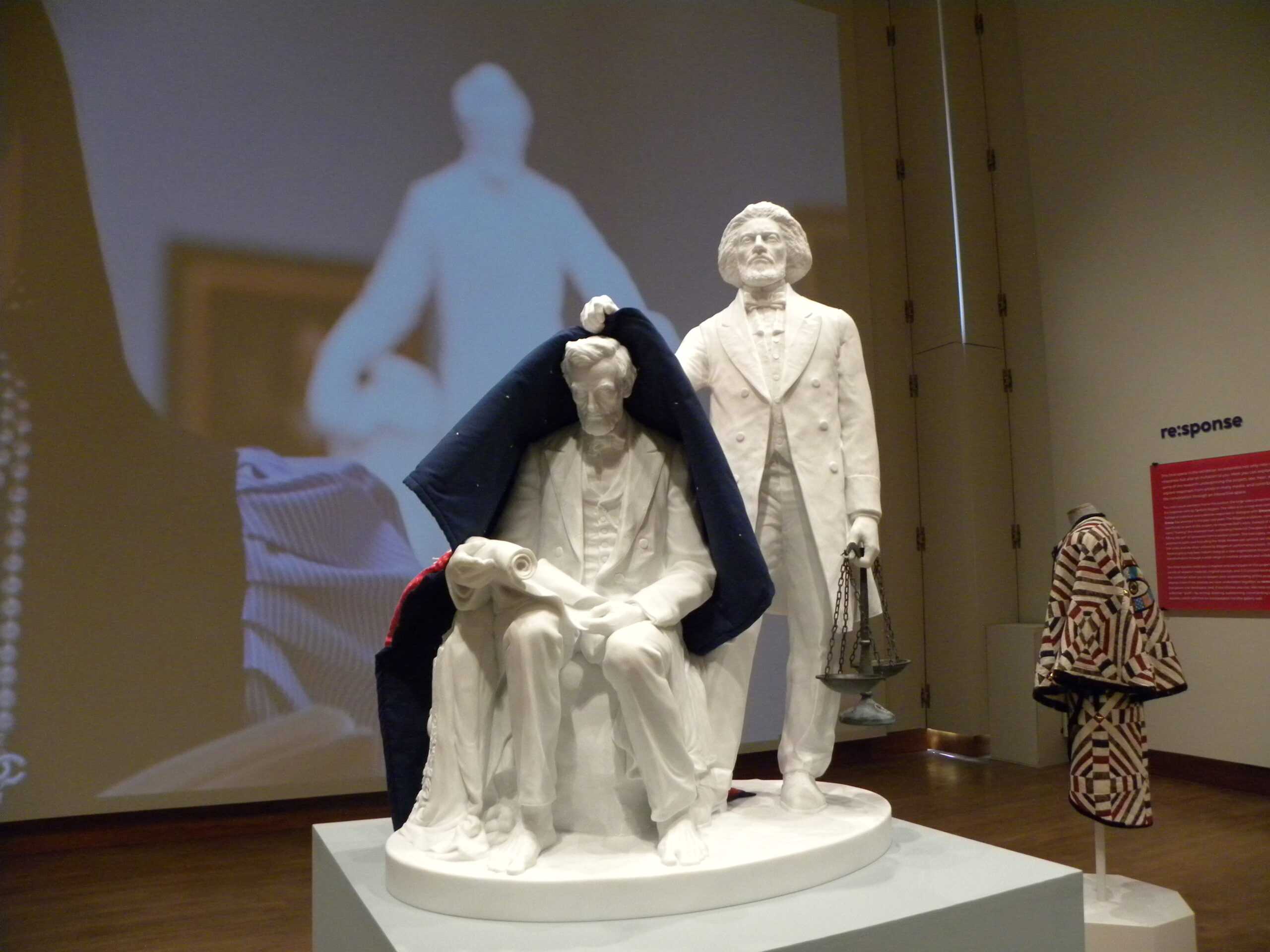

The Chazen Museum of Art revealed the newest addition to its “re:mancipation” exhibit May 4. The sculpture, titled “Lifting the Veil,” is a critical response piece from conceptual artist Sandford Biggers to the problematic 1873 “Emancipation Group” monument.

“‘Lifting the Veil’ serves as an artistic intervention in which we have examined a museum’s collection, acknowledged the complicated histories behind some works and proposed a pedagogical and object-based intervention to illuminate innovative ways of interpreting works on view,” Biggers said in a press release from The Chazen.

The “re:mancipation” exhibition is the culmination of a multiyear collaboration between The Chazen Museum of Art, Biggers and MASK Consortium, which combines art, education and analysis to engage the community in critical dialogues about history, culture and monuments.

The piece of art in question, “Emancipation Group,” features Abraham Lincoln presiding over a kneeling, stereotypical figure representing enslaved people. The sculpture carries a false sense of empowerment, since emancipation and Black freedom are attributed to Lincoln, while a sense of inequality remains.

In contrast, “Lifting the Veil” features Frederick Douglass standing while removing a red, white and blue quilt from the face of a barefoot Lincoln. Biggers’ response piece alludes to “Lifting the Veil of Ignorance,” a monument dedicated to Booker T. Washington at Tuskegee University, and to Douglass, who expressed disappointment over the original reveal of the “Emancipation Group” sculpture.

Celia Hiorns/The Badger Herald

“What I want to see before I die is a monument representing the negro, not couchant on his knees like a four-footed animal, but erect on his feet like a man,” Douglass said in a letter, written days after the “Emancipation Group” dedication in 1876.

“Lifting the Veil” offers such a representation by starting a conversation about symbolism in the original work. Instead of posing Lincoln as a savior, the response sculpture honors Douglass, who presides over the president. The piece explores the complexity of Lincoln and Douglass’ relationship and creates a comprehensive representation of emancipation. But this piece is only one part of the larger exhibition.

Janine Yorimoto Boldt, one of the curators of “re:mancipation,” says not having “Lifting the Veil” ready when the exhibition first opened worked out well, since Biggers wanted the project to focus less on his own work, and more on the community’s response to “Emancipation Group.”

“By not including it originally, it allowed visitors to come and make up their own minds, and to engage with the history of the piece without being overshadowed by his work,” Yorimoto Boldt said.

The full exhibition includes a historical timeline starting with some of the earliest records of slavery and colonization, continuing through to modern-day mass incarceration. This part of the exhibition is accompanied by artworks relevant to the time periods and cultures discussed in the timeline.

As the timeline element continues, visitors encounter a unique representation of an original “Emancipation Group” sculpture, which is surrounded by mirrors. This display emulates exhibition styles of the time period and creates a space for self-reflection, as viewers see themselves reflected alongside the sculpture, according to Yorimoto Boldt. Another depiction of “Emancipation Group” in the exhibit contains an analytical breakdown of each element in the piece, uncovering the symbolism and discussing the problematic themes.

“Our conversations were constantly evolving about what this exhibition really needed to do and the content that had to be in there,” Yorimoto Boldt said. “And that came through really open, honest dialogue with our collaborators and with some of the folks who were doing response pieces.”

This element of dialogue is reflected in an interactive, 3D view showing the original placement of “Emancipation Group” inside The Chazen — situated in a room of portraits of white, wealthy elites, further exacerbating the unequal power dynamic between Lincoln and the Black man in the original sculpture.

As a response to this environment, the new exhibit physically faces portraits of white figures who contributed to slavery and colonization against positive, powerful depictions of historical Black figures. The dialogue sparked from the interaction between these two different interpretations of history are at the heart of what this exhibit intends to do.

Celia Hiorns/The Badger Herald

“For art to do what it does, we have to make sure that those avenues of communication are open, that we do not censor things that we don’t like, but we provide environments where contentious conversations can happen in a constructive manner, not a destructive manner,” Biggers said in an interview on the re:mancipation YouTube channel.

The final section of the exhibition hosts Biggers’ response sculpture, a video loop showing a variety of other response works and an opportunity for community members to contribute their reflections on blank quilt squares. As a whole, the exhibition calls on the public to engage with art and history in a more critical way.

Though Biggers’ response piece is the newest addition to the exhibition, it is one part of a larger project to create a safe space for learning and conversation. Ultimately, “re:mancipation” offers a more comprehensive understanding of the past that can better inform the present and future.

“This exhibition isn’t meant to solve racism, it can’t solve the monument debate, but it opens up a space for conversation,” Yorimoto Boldt said. “The first step is opening your mind before we can really make a lot of change.”

“re:mancipation” is open at The Chazen Museum of Art through June 25.