From 2000 to 2005, a fifth of his 25 years of incarceration, Ramiah Whiteside worked for the Bureau of Correctional Enterprises. While he started stuffing registration stickers into envelopes for 42 cents an hour, Whiteside eventually worked up to lead stock screener, creating Wisconsin’s traffic signs for $1 per hour

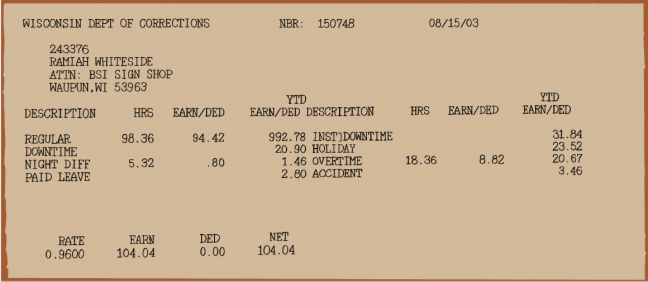

Aug. 15, 2003, Whiteside received a paycheck for working 98 hours, with 18 hours of overtime. His check was just $104.

During the 2018-2019 fiscal year, 440 inmates worked 805,000 hours for the BCE. For those hours, they received $780,000, resulting in an average pay of 97 cents per hour.

The low pay and sometimes hard to process conditions inmates experience in prison labor has garnered attention, with many likening it to modern-day slavery. BCE, however, may be different from the general concept of prison labor that may come to mind.

Contract Controversies

BCE is composed of Badger State Industries, Correctional Farms, Badger State Logistics and their Transition Program. These programs provide jobs to inmates in a variety of industries, from dairy to carpentry. An inmate’s pay depends on the security level of the facility they are at, and which of the industries they work with.

In 2020, the average BCE agricultural and logistic worker earned $1.22 per hour, while industry workers earned 97 cents, according to Wisconsin Department of Corrections Director of Communications John Beard.

The University of Wisconsin System has faced backlash for holding a contract with Badger State Industries, which produces furniture and road signs, among other things, including office furniture purchased by UW-Madison. While many have called for UW to end their contract with BSI, including change.org petitions and other student papers, UW has little choice in the matter and must renew their contract come Dec. 31 to comply with state law.

“The Department of Administration and state statute currently mandate the university’s and UW System’s use of Badger State Industries,” UW communications director Meredith McGlone wrote in an email. “In other words, we are required by state law to purchase certain materials from BSI, ‘when the Bureau of Correctional Enterprises is able to provide comparable products at comparable prices.’ Any changes in that requirement would need to be passed by the state legislature and signed by the governor.”

The current contract with BCE dates back to 2014, according to Beard, with UW campuses purchasing 52% of BCE furniture sold in 2020 for more than $4.6 million.

Worked like “dogs”

Craig Sussek also worked for BCE during his 25 years of incarceration, and constructed some of the very furniture the UW System has purchased. He and Whiteside described working hard for hours on end.

“So, I’m doing back-breaking work, you know,” Whiteside said. “Imagine lifting and turning and shipping an order of 800 stop signs 1,000 stop signs, 200 stop signs, 400 no parking signs or left turn signs. So, imagine doing that work every day, you know Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, sometimes on a Saturday. So, weekly 10-hour days. Go, go, go, go, go.”

With the Fight for Fifteen movement and a current minimum wage of $7.25, $1 per hour seems unimaginable. Whiteside, however, explained that this was not the case for the incarcerated. He explained that BCE pays more than most prison jobs and described them as “the upper echelon,” making them sought-after jobs in prison, a sentiment echoed by Sussek.

In order to apply to work for BCE, an inmate must have earned a high school diploma or equivalent and not have any major rule violations in the previous 12 months. They must then interview for the job before receiving an offer. They can also choose to leave the BCE position if they would like.

But, this did not mean Sussek and Whiteside thought the pay scale was fair for the amount and quality of work BCE workers do.

“It should not be legal to basically oppress, or suppress, a person connected to a criminal conviction or criminal like that,” Whiteside said. “The punishment is you’re removed from society, you’re removed from the community, but to make you work like a mule on top of that for five years, 10 years, 20 years without being compensated — that I think constitutes a level of cruel, cruel and unusual punishment.”

As a Computer Numerically Controlled program operator — a person that operates factory equipment that turns the raw materials into a finished product — Sussek said he would have made $20 to $30 an hour “on the street.” But, when asked how much they believed inmates should be paid for their labor, both responded with numbers well below minimum wage.

Whiteside said the pay scale should start at $1 and cap at $5, while Sussek suggested pay be around $6 an hour. Sussek’s suggestion, however, included the caveat that inmates be unable to access a majority of the funds so they would have what he referred to as a “nest egg” once they were released.

“I honestly think the $6 mark is a fair wage,” Sussek said. “And then you take $5 of that $6 and you put that into a release fund that the inmates cannot touch. Because making $1 an hour in prison is enough to get you your commissary. If you save a little bit, it’s enough to buy your shoes or whatever you need. It’s more than enough to survive in prison. However, when you’re trying to survive in prison, if you don’t have help from the street and save money for your release, $1 an hour is not going to cut it.”

A 2018 report, “Nowhere to Go: Homelessness among formerly incarcerated people” by Assistant Professor of Sociology at Suffolk University and Prison Policy Initiative Advisory Board Member Lucius Couloute, revealed a connection between being incarcerated and being unhoused.

The report found that formerly incarcerated individuals were 10 times more likely to be houseless than the rest of the population. Specifically, it found that 203 out of every 10,000 formerly incarcerated people were homeless and 570 out of every 10,000 faced housing insecurity.

What inmates earn while incarcerated, as it is, does not all go directly to them. Their earnings primarily pay court-ordered payments, including restitution to victims of their crimes as well as child support for dependent children. Funds are also deposited into their release account so they “have available funds upon release, which add to stability and reduce the likelihood of future criminal behavior,” according to the BCE website.

After saving up, Sussek said he was released with about $2,200 in his release account. Sussek said that he had made sure to network while he was in prison so he would have connections when he was released, which paid off. While he was lucky to find a program that helped him with housing costs, Sussek said that if he had to “pay $1,000 a month in rent he wouldn’t be making it out here.”

“They work the guys, and women, like dogs, for not a lot of money,” Sussek said. “Yet at the same time you’re making twice what anybody else makes, and then at minimum, you can make up to $1.60 an hour. So, you’re making more money but they do work you. And like I said, work is the number one emphasis above rehabilitation and training, in my opinion.”

Sussek, however, did emphasize that some people in the program left an impression on him and that “there are people within the institutions [who] actually cared about the men and women that work there,” specifically Dave Jesko, the head supervisor for BSI at the Fox Lake Correctional Institution at the time. Sussek described Jesko as having “compassion to spare.”

A tangle of red tape

When asked about the low wages the inmates earned, BCE Director Wesley Ray agreed that “a reasonable person would consider that low pay.”

But, Ray explained it’s not as simple as just raising workers’ pay rates.

BCE is completely revenue funded, meaning that any money made from selling products goes right into running the program, which includes paying the workers as well as maintaining the necessary equipment.

Just last year, BCE had to replace the 20-year-old combine for their agriculture division. While BCE did purchase a used combine, brand new combines ran for $380,000 to $500,000 in 2019. The farm BCE operates in Waupun also required renovations, including the upgrade of a calf transition barn. These upgrades were part of a multi-million dollar project.

“So, it is low pay, and it’s the way that we can continue to provide these opportunities,” Ray said. “If I paid more, first of all, I’d be breaking the statute by creating a deficit situation through compensation, and second of all, I wouldn’t be able to provide the number of quality experiences that I can provide now.”

Before he was director, Ray said BCE was not “cash positive.” BCE has just become profitable for the first time four years ago, meaning Ray may have the opportunity in the near future to pursue pay raises for BCE workers.

This, however, is contingent on BCE remaining profitable, which is difficult with a limited client base.

“We can only sell to — for office furniture — state customers, but we compete with multi-million dollar multinational companies who can sell to anyone in the world,” Ray said.

For businesses to work with BCE, Ray said there is a complex process to follow, which creates barriers to business growth and partnerships. In order for these things to change, the legislature would have to make them happen.

Recently, when a Wisconsin furniture company was starting up and approached Ray about outsourcing labor through BCE to get started, they went a different route which was less complicated and time-consuming. This opportunity would have allowed BCE workers the opportunity to work in the private sector, thus earning higher wages.

“I think those statutes are quite old, and my peers in other states can change their industry operations, provide different opportunities or additional opportunities to persons in their care, more quickly than we can,” Ray said.

Beyond prison bars

After their release, both Sussek and Whiteside have worked on settling back into life outside of a cell.

Whiteside now works as a Community Organizer for Ex-incarcerated People Organizing, which is a group led by formerly imprisoned people that “works to end mass incarceration, eliminate all forms of structural discrimination against formerly incarcerated people, and restore formerly incarcerated people to full participation in the life of our communities,” according to the EXPO website.

Sussek has spent the last year working to get his vehicle roadworthy and fixing up his apartment. He is currently working on getting an apprenticeship in the plumbing industry and just celebrated the arrival of his stimulus check, which he said meant he could finally start saving for his future. While BCE does provide help for former workers once they are released, Sussek preferred to find his own way.

“They do offer programs when you get out, such as, you know, they help you with resume building, they can help you try finding jobs in certain areas,” Sussek said. “If you get a job like I’m trying to get, a job in the plumbing industry, right now as an apprentice, they would help you with tools or shoes or things of that nature. But I haven’t been leaning on them because I’d rather do for myself than lean on somebody else.”

Ray pointed out that BCE workers are re-incarcerated at lower rates when compared to similar inmates that did not work for BCE. According to Beard, a 2020 analysis by the Department of Corrections’ Research and Policy Unit found that 71% of former BCE workers had not returned to DOC custody three years after release, which is 3% higher than those who did not work for BCE while in custody. The same analysis found that 88% of BCE workers find jobs and still hold them three years after release, which is about 9% higher than those who did not work for BCE.

Ray said he has received communications from former BCE workers, including Christmas cards and video footage from their new job to update Ray on where they are and what they are doing.

“We want to be a small and growing part of their success,” Ray said. “That’s why I say it’s work worth doing.”