“Last Wednesday, he was doing 25 to 30 pull ups a day. And on Friday, there’s talk of him being intubated,” the father of an unnamed former Wisconsin high school athlete said to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. His son had recently been hospitalized in Florida.

The man, admitted to the intensive care unit, told MJS that his doctors said his lungs looked like “a 70-year-olds” and that he felt like he “was going to die.” He was admitted with a fever, chills and symptoms that were originally diagnosed by a private doctor as pneumonia.

As time passed, however, his family found out differently. Doctors at the hospital suggested that his illness was related to vaping with his electronic cigarette.

In early August, the Wisconsin Department of Health Services confirmed 11 state cases of teenagers and young adults with severe lung disease. Patients were noted to have shortness of breath, fatigue, chest pain, cough and weight loss, with some needing assistance to breathe.

The key takeaway, however, was sobering. Dr. Barbara Calkins, a pediatrician with Westbrook Pediatrics of the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, summarized the hospital’s initial warnings.

“On July 25th, Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin warned the public of the potential danger of vaping for those who are underage after we reported eight cases of hospitalized teenagers with seriously damaged lungs to the Wisconsin Department of Health Services,” Calkins said. “Vaping was the only commonality among all of the patients.”

Early beginnings

Vaping, according to the Center for Disease Control, is the use of an e-cigarette. The vapor is produced by the device heating a liquid that usually contains nicotine, flavorings and other chemicals that help to make the aerosol.

The vapor is then inhaled, both by users into their lungs, and by bystanders who can breathe it in when the user exhales into the air.

Niru Achanta, a junior at the University of Wisconsin, said he vapes “almost daily.” He talked about how he first became interested in vaping in high school.

“In high school, I thought the [vaporous] clouds were cool,” he said. “As time went on, I mainly used it for semi-stressful situations like [homework] and family parties.”

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, 9.5% of students have tried an e-cigarette by the eighth grade. That number rises to 16.5% in the twelfth grade.

Furthermore, the Food and Drug Administration states 1.5 million more middle and high school aged students used e-cigarettes in 2018 as compared to 2017. This correlated to a 78% increase in high school students’ use, and a 48% increase in middle school students’ use.

According to a statement from Marlena Holden, Director of Marketing & Health Communications at University Health Services, the use of e-cigarettes has quadrupled among incoming UW students since 2016.

Max, a sophomore at UW who requested to go by first name only, said he started vaping in college. He cited “party culture” as an introduction to vaping. “When you go to parties, a lot of people have [e-cigarettes] and they pass them around or offer them [to you], especially the first couple times when I said I had never tried it or that I didn’t have one,” he said. “Eventually, I was sort of like ‘well, it’s annoying to have to hit someone else’s’ because I started wanting it during the day … so I went and got one and hit it way more after that.”

Doug Jorenby, Director of Clinical Services for UW Center for Tobacco Research and Intervention and a professor of medicine, cited a Badger Herald article where UW staff accessed statistics from AlcoholEDU and discovered that 20.9% of incoming students reported past usage of e-cigarettes.

Jorenby said that the 20.9% rate couldn’t necessarily be extrapolated to define all undergraduate usage, but that he wouldn’t be surprised if it was around that benchmark.

An (un)healthy alternative

Max said he felt that many UW students, and people in general, thought that e-cigarettes were “healthier” than cigarettes. This, he said, makes them more inclined to try an e-cigarette when offered one as opposed to a cigarette.

According to Jorenby, e-cigarettes, to some extent, can involve different risks than cigarettes.

“E-cigarettes definitely don’t involve the same risks as cigarettes,” Jorenby said. “To put that into context, we look at what we’ve learned from the mid-1950s and onwards, where we’re looking at health effects of smoking globally … Generally, [a large percentage of] longtime cigarette users will face very serious health consequences that can and often do result in death. It’s very sobering when you think about that, and the legality of cigarettes. Compared to that, vaping is almost certainly lower risk.”

According to the CDC, cigarette smoking causes about one of every five deaths in the United States each year. The web page also adds that, in longtime users, quitting smoking before the age of 40 reduces risk of dying from smoking-related diseases by approximately 90%.

Jorenby added, however, that the negative effects of cigarettes do not eliminate the negative effects vaping can have.

“This doesn’t mean that [e-cigarettes are] risk free. In terms of the science of things, we’re badly playing catchup — e-cigarettes came out of nowhere for the public health community,” Jorenby said. “We’ve already got some solid scientific data about specific risks to pulmonary health that are unique to vaping. It’s not on the magnitude of inhaling tobacco smoke, but those risks are there.”

The Chicago Tribune reported on Adam Hergenreder, an 18-year-old from Gurnee, Illinois. He was hospitalized in a case similar to the Wisconsin athlete.

Hergenreder told the Tribune he and his friends didn’t believe “how dangerous [vaping] is.” He continued to vape regularly, up to one and a half pods a day — and wound up in the hospital, where he was taken after days of vomiting.

From his hospital bed, he told the Tribune that he was glad to be an example.

“[Vaping products] aren’t good at all,” Hergenreder said. “They will mess up your lungs.”

Harmful effects

Dr. Bill Kinsey, UW’s chief health officer and medical director of UHS, specified that the effects of vaping can be difficult to gauge.

“[E-cigarettes] emit a vapor that contains harmful chemicals and the effects on the health of the user, and those around them, are largely unknown,” Kinsey said.

Secondhand tobacco smoke has been well-known to cause harmful health effects to bystanders. According to the CDC, secondhand smoke causes over 7 thousand deaths annually from lung cancer and over 30 thousand deaths annually from heart disease.

Darcie Warren, Coordinator of the Partnership for Tobacco Free Wisconsin with the American Lung Association, went into detail on e-cigarette long-term effects.

“The inhalation of harmful chemicals found in e-cigarettes can cause irreversible lung damage and lung disease. Questions about long-term and lasting damage to patients will need to be studied,” Warren said. “We know the brain isn’t fully developed until around age 25, and the addictive nicotine found in flavored tobacco products and e-cigarettes slows brain development. Nicotine use can cause problems with attention, learning and memory.”

Achanta said the debate surrounding cigarettes and e-cigarettes can be “complicated.”

“On one end, vaping can help overcome nicotine addiction,” he said, adding that he did think vaping publicly was still “obnoxious.”

Paying the price: How UW’s drinking culture impacts community as a whole

A trade off

The CDC lays out an abundance of suggestions for overcoming a vaping addiction. One page on their website states that e-cigarettes “have the potential to benefit adult smokers … if used as a complete substitute for regular cigarettes and other smoked tobacco products.”

On a different page, the CDC states in all capital letters that “E-CIGARETTES ARE NOT CURRENTLY APPROVED BY THE FDA AS A QUIT SMOKING AID.” On the same page, it’s stated that evidence from two randomized, controlled trials “found that e-cigarettes with nicotine can help smokers stop smoking in the long term compared with placebo (non-nicotine) e-cigarettes.”

That page adds that many people who choose to vape as a method of fighting addiction wind up not quitting, and instead use both methods.

In addition to the CDC, Jorenby added that when people use e-cigarettes to stop smoking, many people will end up losing at both.

“They’re vaping some of the time, and then they’re also smoking some of the time,” Jorenby said. “We don’t have a good handle on how dynamic that is. Do they in fact give up the smoking? Do they give up vaping?”

Jorenby cited research he conducted with Megan Piper, an associate professor and a lead researcher at UW-CTRI.

According to the work, a cohort of both smokers — defined as using at least five cigarettes per day for six months and no e-cigarette use in three months — and dual users — defined as having smoked daily for three months and using e-cigarettes at least once per week for the past three months — completed baseline assessments. These assessments included demographics, tobacco use and dependence. The participants also provided breath and urine samples.

“We followed these people for two years,” Jorenby said. “We weren’t making suggestions on their behavior, they just did what they did and we collected that information. We met them once every few months in person, and called them in between that.”

The study notes that when they recruited, they deliberately oversampled dual users. Details of the cohort population include that slightly more than half were men and 32.2% lived with a partner who smokes.

The study also noted that there were “significant differences between exclusive smokers and dual users on race, education, and self-reported psychiatric history measures.” Overall, dual users were found to be more likely to be white, younger, have more than a high school education, report a psychiatric history and live with someone who used e-cigarettes.

“We just finished our two year follow-up, but we’ve taken a deeper look into the first year data,” Jorenby said. “About 30% [of people] who came in as dual users actually stopped vaping the first year and went back to smoking full time. Very few people progressed to not vaping or quitting all nicotine.”

The study noted that the results indicated that smokers and dual users took in approximately the same amount of nicotine per day. This suggests that dual users may compensate for smoking fewer cigarettes by obtaining additional nicotine from e-cigarettes.

Jorenby added that there are risks involving cigarette smoking even if you start vaping with the intention of never smoking.

“Something we’ve known for a couple of years now is that among adolescents — people younger than typical undergrad — who had never tried tobacco but started vaping, were between three to four times more likely to go on and start smoking,” Jorenby said. “There’s a really strong signal that if you pick up e-cigarettes because they’re not tobacco or not combustible, you still have greater risk later on to switching over to cigarettes.”

According to a 2017 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics, use of e-cigarettes with higher nicotine concentrations at the baseline was associated with greater levels of combustible cigarette and e-cigarette use at follow-ups, along with a greater intensity of daily use.

At a campus level

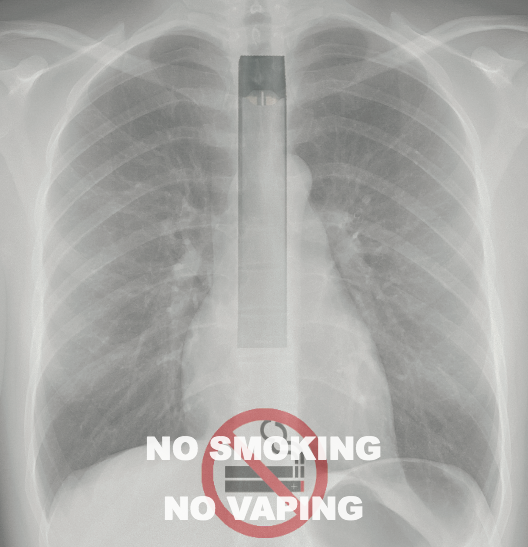

According to Holden, UW updated its campus smoke-free policy in 2016 to include e-cigarettes.

The policy states that smoking is prohibited in all buildings, facilities and vehicles owned, operated or leased by UW. The policy specifies that “smoking” not only includes the burning of any type of lit device, but also “any other smoking equipment or the use of electronic smoking device including, but not limited to, an electronic cigarette, cigar, cigarillo, or pipe.”

Kinsey said by reducing and potentially eliminating the use of nicotine products on campus, UW can continue “efforts to provide a safe and healthy environment for students and employees.”

Holden said UHS offers help to students who are interested in strategies for quitting smoking or e-cigarettes, including free individual counseling.

Warren added that campus policy can impact those trying to quit as well.

“Unfortunately, nicotine is hard to quit … However, we know that having a supportive environment helps smokers quit,” Warren said. “That’s why it’s important to have strong 100% tobacco-free college campus policies in place to deter young adults from starting and to support people ready to quit.”

Along that line, Warren said several colleges throughout Wisconsin have already implemented policies that target protecting their campuses from secondhand smoke and secondhand aerosol.

Regarding recent hospitalizations, Warren said the trends thus far have been concerning.

“While much remains to be determined about the reported cases of severe lung disease as well as the lasting health consequences of vaping, CDC and FDA have made clear that vaping and e-cigarette use is not safe,” Warren said. “The American Lung Association has been raising the alarm about e-cigarettes and their use for more than a decade.”

Warren called the recent cluster of pulmonary illness “deeply worrisome,” and reiterated her concerns about all tobacco products, not just vaping or smoking.

Calkins had a jarring note for anyone who thinks they won’t be affected.

“It can happen to anyone,” she said.