For many years, Taco Bell asked customers to “think outside the bun.” Ever since the fast food chain’s State Street location applied for a liquor license just over a year ago, some in city government want the restaurant to think outside the bottle.

Though a majority on the Alcohol License Review Committee voted to grant the Taco Bell Cantina on State Street a liquor license, Ald. Paul Skidmore, District 9, opposed the license, as he was concerned about the consequences of increased availability of alcohol in the community.

“On one hand you could say, ‘for goodness’ sake, it’s only a Taco Bell. You go there to buy food, you’re only going to have a few drinks and it’s going to be very expensive,’” Skidmore said. “True, but you could go next door and you could buy alcohol or you could go next door to that and get alcohol or you could go to a bar on the corner. Does every place need to have a liquor license?”

For city officials who have fought the license, the answer is no, and for every push Taco Bell has made to sell alcohol with their chalupas and quesadillas, the city has pushed back just as hard.

Which is City Attorney Mike May sent an email earlier this year to Mayor Paul Soglin and the Madison City Council regarding the Taco Bell Cantina on State Street.

“As we recently told you, the Circuit Court ruled against the city’s decision to deny the liquor license on State Street.” May said in the email. “I have reviewed the decision … We have determined to appeal the ruling.”

Madison’s City Council originally voted to grant the business a liquor license last year, but Soglin vetoed the move. The appeal marks yet another chapter in the Taco Bell saga — an affair that has been closely covered at every step. The debate on whether to allow the restaurant on the 500 block of State Street to sell alcohol has been contentious.

But Taco Bell is only the jumping-off point for a much larger conversation. Concern about the prevalence of drinking in the downtown area and its potential adverse effects have raised questions about what actions — if any — the city should take to keep drinking under control.

With unusually competitive municipal elections this year prefacing decisions that will have huge implications for the downtown area, the fate of liquor licensing remains uncertain.

Disturbing the peace

On any given Saturday at 1 a.m., the majority of the city of Madison is soundly asleep. While the rest of the city slumbers, a platoon-sized force of officers are awake downtown. The bottom of State Street and the 600 block of University Avenue are the most heavily patrolled regions of the city, Jason Freedman, the Central District Captain of Police, said.

“There’s a reason for that,” Freedman said. “The reasons are the sheer quantity of humanity and alcohol that are interacting.”

The combination of large crowds mixed with alcohol consumption breeds conflict, Freedman said. His officers have encountered everything from public urination to assault on weekend nights. Alcohol and crowds, Freedman said, impact decision-making and can make people more vulnerable to crime.

Julia Sherman, the senior outreach specialist for the Wisconsin Alcohol Policy Project, said that higher concentrations of alcohol outlets, like the downtown area in Madison, correlate with higher rates of alcohol consumption, crime and disorder.

“There’s been research emerging since the 80s,” Sherman said. “It crosses countries and it crosses cultures. It’s not about Madison, it’s not about Wisconsin, it’s about the fact that we’re all human.”

Alcohol has been on Freedman’s mind too. Close to a year and a half ago, the Madison Police Department analyzed data on the downtown area and saw that there had been a spike in violent crime.

“I grew up in Madison, I went to UW-Madison, I’ve been a cop a long time,” Freedman said. “We’ve always had issues downtown because of alcohol and density, but what we saw were significant increases in some of these more violent offenses that really made us pause and say, ‘OK, something has changed, we’ve got to do some different things.’”

Rowdy crowds and the rise of violence are not the only concerns being raised for the downtown area.

The prevalence of businesses selling alcohol has also affected the downtown ecosystem, according to Soglin and others on the city council. Downtown property owners know that tenants who sell alcohol can generally afford to pay more in rent, Soglin said, and faced with rising rent costs, retailers are driven out of the downtown area.

Tiffany Kenney, executive director of Madison’s Central Business Improvement District, is skeptical that alcohol is driving retail off of State Street. Converting a retail space into a restaurant space can cost a property owner hundreds of thousands of dollars, Kenney said.

“Most property owners don’t really want to convert their property from one to the other,” Kenney said. “It’s a really expensive endeavor. What I do think is that we’ve got smart property owners who are trying to figure out a really diverse mix of buildings downtown.”

Another concern of the city is the cost of keeping the downtown area safe. Doing so requires a lot of manpower — anywhere between six and 26 cops in addition to the eight police officers already on patrol in the area.

This presents a challenge for Freedman, who says filling the assignments can be difficult at times. The hours are late, the weather conditions can be extreme, and many of the interactions police have are with drunk people.

“It’s certainly not seen as a cush, easy way to earn money,” Freedman said.

The city does what it can to encourage officers to take overtime hours, but policing State Street doesn’t come cheap. Ald. Mike Verveer, District 4, said the city spends between $100,000 and $200,000 a year on police overtime.

Alcohol is also the number one reason behind calls for police — more so than any other drug, Freedman said. After 22 years in law enforcement, Freedman said that he is comfortable saying that the downtown area would be better off without the heavy drinking behaviors so commonly seen in the central district.

Fermenting chaos

While pedestrian and transit malls across the country have failed, State Street has proven to be an exception to that rule. Verveer gives credit to Soglin for building State Street into what it is today — arguably the most famous street in the state.

“We survived the regional shopping malls,” Soglin said. “Now we are in effect a victim of our own success — namely the attraction of out of town and local money that want to sell large quantities of alcohol.”

Twenty years ago, retail made up 50 percent of all greater State Street area businesses, according to the 2018 State of the Downtown Report. But last year, retail made up only 22 percent of State Street businesses, although that total number almost doubled over that stretch of time.

Verveer, who sits on the Alcohol Licensing Review Committee, said previously the city allowed too much alcohol growth downtown.

“I might go so far as to say we came close to creating a monster,” Verveer said.

Sherman said expectations for the downtown area have changed in the past 10 years as more high-end housing entered the space. With high rises now located so close to the downtown area, concerns over noise and trash were quickly brought to light.

“Those considerations are always going to be there now, because there are some really great homes,” Sherman said. “The issues changed as the downtown has changed.”

Sherman also said until around a decade ago, new bars were considered a positive economic development because they were businesses that served as a source of employment and brought people to the community. Now, Sherman said, there is growing recognition that bars are not a positive economic development and are in fact a drain on the city’s resources.

“Not all businesses are equal,” Sherman said. “Some will cost you more in the long run, and alcohol is one of them.”

Freedman said he’s quick to point out that Madison’s bars are not the only cause behind downtown’s heavy drinking problems.

Outside of the bars, Freedman said, more can be done to make public spaces downtown safer, and to dismantle the strong drinking culture among UW students.

“The bars have been there forever,” Freedman said. “The upticks in violence are more recent. That would suggest to me that, while the bars play a role in this, they’re not necessarily generating some of these issues.”

Freedman said he doesn’t have a clear answer as to why violent crime is rising on State Street. But he speculated that a handful of key factors have contributed to the trend.

In recent years, Freedman said he has seen an overall increase in violence throughout the city, a rise in harmful drug and alcohol practices, such as ordering drugs off the internet and greater levels of defiance toward police.

But the most significant factor, Freedman said, is that there are simply no other large venues open into the late night with no cover charge and less limited hours of operation.

“There’s a vacuum,” Freedman said. “You have a vacuum where there’s a lot of alcohol, there’s a lot of people, there’s the anonymity of the crowd, and it’s a reflection of the broader societal trends.”

Hangover issues

For years, the city of Madison has enforced an alcohol overlay district, an ordinance which bans new alcohol licensing for bars and liquor stores in the downtown area.

The ordinance stretches across the 500 and 600 blocks of State Street and University Avenue, between Broom Street and Lake Street. The measure has kept several businesses, such as the 7-Eleven on the corner of Lake and State Street, from acquiring liquor licenses. The alcohol overlay district does not prohibit the city from granting liquor licenses to restaurants.

But written into the ordinance is a sunset provision, which will cause the alcohol overlay district to expire in June, just after the next city council and mayoral election in April. Not only is it possible that Madison will have a new mayor, but facing an unprecedented number of retirements from the council this year, many seats will be filled with newly elected council members.

One of the first issues the council will face is deciding whether or not to keep the alcohol overlay district in place.

“By the end of the semester, these conversations will really be coming to a head in many respects,” Verveer said.

It’s hard to foresee how this new council will respond. Liquor licensing, Verveer said, is not a commonplace topic that candidates bring up when they campaign door-to-door.

The most notable attempt to address liquor licensing in the downtown area came last year when Soglin proposed a moratorium that would have extended the existing hold on liquor licenses to include the vast majority of State Street and stretch as far down as West Washington Avenue. Verveer initially worked with the mayor on the plan but parted ways when they couldn’t agree on specifics — particularly those surrounding restaurants within the affected area.

The proposal gained little traction and was quietly dropped. Instead, the council adopted a separate resolution to launch a study of alcohol density across the city. The methodologies of the study were presented at a ALRC meeting Feb. 20 and the findings of the study will be presented in June — the same month in which the sunset provision of the current moratorium takes effect.

Kenney said she believes it is time for the sun to set on the license hold downtown. For the many years it has been in place, there has been no evidence that the measure has been successful in curbing negative alcohol consumption, Kenney said. She added that the city could be more effective focusing its limited time and resources on treating the effects of binge drinking and supporting viable alternatives to drinking on State Street, such as the Madison Night Market.

“Community energy would be better spent on [other] solutions than an additional moratorium because we’ve had one that hasn’t really made any impact, positive or negative,” Kenney said.

Skidmore, who serves on the ALRC, agrees that the moratorium is not a full solution, but he said that it’s important to call a timeout to study those problems — not add to them.

“You don’t throw gas on a fire to put it out,” Skidmore said.

Restaurants aren’t explicitly prevented from having a liquor license as a part of city ordinances. But Soglin has attempted to prevent several restaurants from obtaining liquor licenses — most notably, Taco Bell, but also Mad City Frites and Lotsa Pizza, both of which were formerly housed on State Street.

The city has also stopped downtown restaurants from selling late night alcohol.

This can put restaurants in the State Street area in a tricky situation. Restaurants sometimes operate on slim margins, and not being able to sell alcohol can impact their ability to survive financially downtown.

Freedman said he cannot support granting liquor licenses to any downtown businesses in problem locations. His focus is on public safety and the wellness of the community. Freedman said the interests of the businesses are sometimes in conflict with the interests of the broader community.

“We’ll have a restaurant come in and they have good ownership and good management,” Freedman said. “I’m very confident they’re good people, but I say, ‘while I have no concerns with you as ownership, because of where you are looking to open … I can’t advocate or support your trying to sell alcohol after midnight.’”

This is what makes the fate of the Taco Bell lawsuit so important. The initial ruling claimed that the city acted arbitrarily in denying the restaurant a license. May said requiring the city to provide justification for every alcohol license denial is too stringent of a requirement.

The city’s primary concern is not the individual license, but that it may put the city in a difficult situation, May said. Everytime the city denies a license, the city will be forced to spend a large amount of time justifying the differences between two establishments.

It’s rarely restaurants that are troublemakers downtown, Verveer said. On the rare occasion that they do cause trouble, it’s usually been because they morphed into a tavern during late night hours.

This is what caused Verveer to part ways with Soglin, who desired to expand alcohol serving limitations within his proposed moratorium.

“My perspective is that I would rather have a restaurant than a vacant storefront on State Street,” Verveer said.

City Council rejects move to ban new alcohol licenses on campus

Another concern, which led to the creation of the alcohol license density study, is that combating alcohol sales at bars may just lead to higher rates of pregaming. If Madison doesn’t tackle both, they may just end up pushing the problem around, Sherman said.

“No one in Wisconsin has to go too far for a drink, whether they buy it and take it home, or buy it and drink it there,” Sherman said.

Final call

Many do think that they can effectively make the downtown region a safer area.

When the 600 block of University saw a spike in violent crimes — many of which involved weapons — police took action. In 2018, the city put around $80,000 into better lighting in the area and mandated that none of the bars in the region allow new entry after 1:30 a.m.

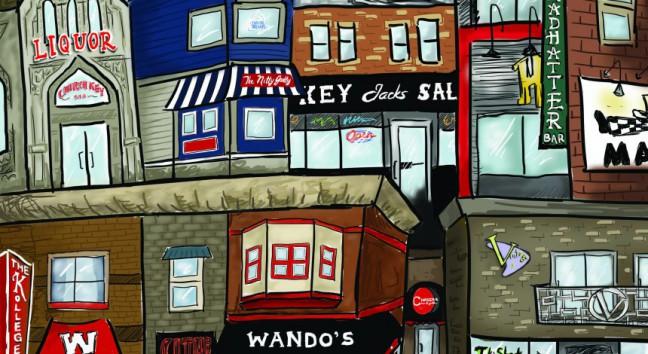

Officers downtown believe the 1:30 a.m. rule has been effective in curbing problem behavior. There have been talks of expanding the measure to include a greater expanse of the downtown and campus area, including well-known hangouts like The Kollege Klub, Whiskey Jack’s and City Bar, among others.

There has also been renewed conversations with UW about introducing ID scanners to bars and liquor stores across the downtown area.

City officials have considered shifting more financial burden of downtown safety measures onto bar owners. Alcohol licensing fees in Madison range between $500 and $600. In comparison, the average cost of liquor license fees across the country was just over $1,400 as of June 2018. Verveer said that out-of-state entrepreneurs looking to open a new business in Madison are blown away by how little it costs.

Madison currently has no plan to offset the cost of drinking by increasing the fees bars pay to the city. But the study could give the city enough data to support adding a special charge to certain properties that see a disproportionate number of calls for service, Verveer said.

Ultimately, many of the policy decisions that will be made this spring and summer are dependent on the results of upcoming city elections and the findings of the alcohol density study. While conversations may differ about what policies are best for Madison’s beloved downtown, one thing is certain — it’s going to take a lot of work to change the region.

“There are no magic bullets in this sort of public policy debate,” Sherman said. “No one thing is going to remedy the problem.”