Shorty stands on the end of the 600 block of State Street handing out issues of Street Pulse, Madison’s homeless cooperative newspaper.

Before becoming a vendor for Street Pulse, Shorty, who asked to only be identified by his nickname, was homeless.

“About three years ago … I didn’t have a place,” Shorty said. “All of sudden, I’m hearing all of these people … like me are getting places.”

He went to Bethel Lutheran Church, where he filled out an application for the federally-funded Housing Choice Voucher program for low-income housing.

About a year later, he was accepted.

The Housing Choice Voucher program, known as Section 8, pays a portion of low-income tenants’ rent. About 1,600 households in Madison are funded through this program.

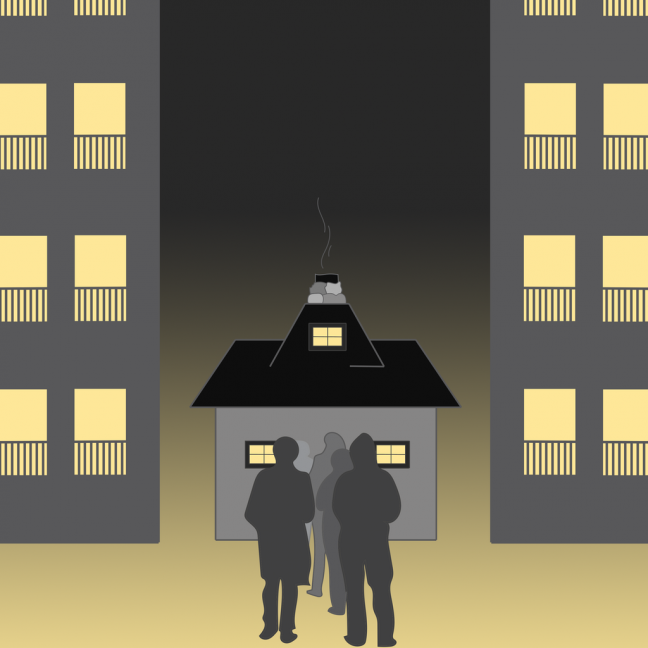

Through Section 8 and other Madison initiatives, the city has seen an increase in efforts to house individuals experiencing homelessness that have previously been absent.

Despite Madison’s efforts, Jani Koester, Homeless Services Consortium of Dane County board president, said the city isn’t keeping up with the demand for housing for low-income tenants.

“There just isn’t enough housing,” Koester said. “We’re not keeping up with the demand … as soon as we build it and we have it, it’s full.”

When Madison/Dane County Continuum of Care surveyed the streets and homeless shelters in January, a process that yields a point-in-time count, they saw about 614 individuals experiencing homelessness, a 4.9 percent increase from the previous year’s count.

And while that number provides a snapshot of the homeless population on a given night, the number is “undoubtedly higher” than estimated.

Though the city has made strides in providing resources and moving Madison’s homeless population into housing, it is only starting to address the shortage of units and funds available.

A limiting definition

Homelessness is a spectrum. When obtaining affordable housing, many individuals who are homeless for a short time never access the homeless resources system again after receiving the assistance.

Others may have larger challenges and need ongoing, one- to two-year financial and social assistance, like job training or child care services, Matt Wachter, the city’s real estate manager, said. Once they get themselves established in secure housing, they may still need ongoing assistance.

On the other hand, those who receive rent assistance while in rapid rehousing — which provides individuals short-term financial stability to obtain a low-rent apartment — they still need to secure a stable income stream to continue affording housing, Wisconsin Homeless Coalition executive director Joe Volk said.

Some need assistance for years or the rest of their life, Wachter said. To accommodate those needs, the city has partnered with developers to provide health, social and support services when individuals rent affordable housing units.

For different needs, there are different resources needed. But the reality is that there aren’t always enough funds to address the vast array of issues confronting the diverse homeless population.

Volk said this diverse population includes youth, individuals who are experiencing mental health issues, those facing economic crisis and more.

That said, addressing homelessness doesn’t lie in one single remedy. At the same time, the existence of numerous federal definitions makes it difficult to come up with any remedy at all.

“The federal government can’t decide on a single definition of homelessness and I think it’s really connected to resources,” Koester said. “If you don’t broaden the resources that come with it, you’re not going to be able to serve everyone who’s identified.”

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development tackles the issue with a “one approach for all” solution, Volk said.

HUD defines homelessness in four categories. The first being someone who is “literally homeless,” or an “individual or family who lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence.” Individuals under categories two, three and four are at “imminent risk of homelessness,” “homeless under other federal statutes” and “fleeing/attempting to flee domestic violence,” respectively.

The narrow definition can have deafening results for individuals not only across Madison and Dane County, but the country at large. For example, Volk said HUD won’t fund shelters or transitional housing.

Rather, Volk said many of their funds are directed toward supportive housing, which is only one piece of the larger puzzle.

Other definitions, like that of the Department of Education, operate under a much wider lense of homelessness. This allows them to count more individuals experiencing homelessness on a given night, Linette Rhodes, the city’s interim community development grants supervisor, said.

Under that definition, school districts, for example, would count individuals who don’t have a stable home or are “couchsurfing” as homeless, while the Madison/Dane County Continuum of Care only looks at those who are in shelters, Rhodes said.

In other words, some families and youths who the Department of Education’s definition consider homeless cannot access resources under the HUD definition — more than 75 percent of families in Madison’s schools who identify as homeless don’t meet HUD’s definition, Koester said.

Michael Luckey, director of the Wisconsin Interagency Council on Homelessness, said the multitude of definitions then creates a gap in trying to determine who is homeless and allocating funds toward those individuals who don’t meet the definition.

“One of the areas where the state can fill the gap is by focusing on every type of homeless — whether that’s those who identify as homeless in our schools or identify as homeless under housing programs,” Luckey said.

‘You just gotta take it’

HUD funds local municipalities to help combat homelessness, Koester said. Every year, HSC looks at their priorities, which are based on data like the point-in-time count, and uses the funds accordingly. Last year, HSC prioritized housing families, which saw a 22.6 percent decrease in 2018’s point-in-time count from the prior year.

Right now, their priorities lie in housing singles, or individuals without children, Koester said. Madison/Dane County Continuum of Care saw a 27.4 percent increase of singles and a 42.5 percent increase of those who are chronically homeless.

“There’s not enough housing to even make a dent in the [priorities] list,” Koester said.

In Madison, there’s one men’s shelter service, provided through Porchlight; one youth shelter, provided through Briarpatch Youth Services; one women’s shelter and one family’s shelter service, both of which are provided through Salvation Army of Dane County, according to the HSC website.

University Housing offers overpriced options compared to other large universities

Porchlight, which houses an overnight shelter through Grace Presbyterian Church and has two overflow shelters, provides two meals, laundry services and other day-to-day needs for individuals experiencing homelessness, development director for Porchlight Jessica Mathis said. Additionally, they operate a mental health shelter for both men and women.

But Porchlight operates on a 90-day limit rule, where individuals can only use the overnight shelter 90 days out of the year, according to their website.

Part of that is because of space, but Madison also has a mission to use shelters as an emergent need and to make stays there as brief as possible, Rhodes said.

“One of our overarching goals in homelessness is to make … the experience of homelessness rare, brief and non-recurring,” Rhodes said. “One of the performance measures we put on the shelter is the length of stay overall that people have. And our goal is to shorten people’s stay they’ll have at the shelter.”

Shelters serve as “access points,” where individuals experiencing homelessness can get connected with case management services or with resources around the city, Rhodes said.

Through these access points, Mathis said the key for these services is to give homeless individuals long-term solutions, like teaching them how to budget.

For Shorty, he got connected to these resources through a friend that also worked at Street Pulse.

“Before I was doing Street Pulse, I was out here on the streets selling drugs and panhandling at bus stops until it just got to a point where I just got sick and tired of being sick and tired,” Shorty said. “There are resources here. You just gotta take it.”

A changing Madison market

Approximately $9.3 million in funds from both public and private sources went toward homelessness initiatives in the 2016-17 Community Development Division budget, $1.1 million of which comes from the city.

The largest portion of the $9.3 million was allocated toward permanent housing, which accounted for just under $2.2 million.

Still, there are not enough funds and there are not enough resources to connect everyone with housing, Koester said.

“If you don’t have access to those programs, then you’re out there on your own,” Koester said.

And when individuals eventually find housing, the rising rent can put them in circumstances where they may not be making a wage that can support themselves in that housing.

Madison has seen a dramatic growth in rental housing over the past ten years, Wachter said. Though the city has added 1,500 to 2,000 apartments per year, it isn’t enough to keep up with the growing population.

In recent years, Madison’s vacancy rate has been around 2 percent; in some areas of the city, it was 1 percent, Wachter said. Right now, the city of Madison’s vacancy rate is at 3 to 4 percent, while a “healthy” vacancy rate is 5 percent.

A safe place: Legislation pushes sober housing development in Wisconsin

“When vacancy rates get that low, landlords should be a lot more picky about who they rent to because they have waiting lists of people oftentimes for these units,” Wachter said. “If you own an existing unit and you’ve got a lot people who are demanding it, you can charge more. So we’ve seen rents go up fairly dramatically in the city of Madison.”

Because of the increase in demand and in construction costs is driving up the prices of units in an already tight market, there were years where there was a shortage in housing, Wachter said. This, in turn, had a detrimental effect on the lower-income side of the renters pool. The number of affordable options is small in comparison to the rest of the market.

Luckey echoed Wachter’s sentiment. He said because of a fast-growing population and development of unaffordable housing options in Madison, it has been difficult getting people into housing they can afford.

For an average one-bedroom apartment, a worker making minimum wage would have to work 90-hour weeks to afford rent for that unit, Mathis said. This doesn’t include other living expenses.

The isthmus is a hotspot not many people can attain, Rhodes said. Not only do low-rent apartments tend to be on the outskirts of the city, they are also occupied, presenting a new challenge of incentivizing people to stay in the city.

To combat those circumstances, the city does provide subsidized housing throughout the city through Section 8, where they pay a portion of a person’s rent through a lottery system.

Those who obtain the housing voucher pay 30 percent of their annual income and the voucher pays the rest, Wachter said. Otherwise, individuals would have to be making at least three times their monthly income to even consider the possibility of affording the apartment’s rent.

That way, people will also have flexibility in where they want to live and can move if they want or need to.

But that program hasn’t been growing and neither have others that provide low-income rent, Wachter said.

Instead, the city has “latched onto” the Section 42 tax credit program, a well-funded initiative that awards tax credits to states, which private developers can apply to build apartment buildings, Wachter said. The tax credits fund about 50 to 70 percent of construction costs on the condition that they reserve units for individuals making a mix of income levels and charge them a rent they can afford.

Through this program, the city has created the Affordable Housing Fund, which developers use to apply for funds to create buildings in certain areas of the city for a mix of income levels. These areas usually are along bus routes, near grocery stores and generally where individuals have the best chance of succeeding, Wachter said.

The city had a goal to build 1,000 new units in five years with these funds and they’re on their way to succeeding, Wachter said. More than 700 units have been built since 2014.

Nevertheless, there are still individuals who are limited in housing choices due to barriers like low credit or eviction records, Mathis said.

To counteract that practice, Rhodes said they have created “housing navigators,” which provide resources to help in filling out applications and determining where to apply for housing.

In the 2019 county budget, Rhodes said the county is allocating additional funds toward more housing navigators to place a larger emphasis on pairing youth with affordable housing options as a way of preventing homelessness before it happens.

Still, as the city works to provide options for housing, inevitable stereotypes and myths about individuals experiencing homelessness persist.

Working toward a better community

While the city progresses toward a more comprehensive understanding of how to combat homelessness despite limits in funds and definitions, the onus of creating a better community as a whole falls onto its members.

There’s a common myth that homelessness is a choice, but homelessness isn’t something many choose, Mathis said. Rather, the majority of people experiencing homelessness are children, far from the common perception.

“There’s definitely a disconnect between what the general person who is experiencing homelessness is, and who is actually most affected by homelessness in the Madison community,” Mathis said.

There are myths that individuals who have experienced homelessness are not good tenants and can’t budget, which simply isn’t true, Koester said.

“We have a lot of clients who are very good tenants,” Koester said. “But if you don’t have a living wage to keep affording the living home that you have, then it’s hard to maintain a good relationship with your landlords if you’re always late with payments.”

Luckey said the simplest, yet often “most challenging” way to debunk these types of myths is by having conversations with individuals who have experienced or are currently experiencing homelessness about their path in life. Visiting and volunteering at shelters also provides that invaluable experience, he said.

For Shorty, when he’s handing out newspapers, he said he’s largely ignored by passersby.

“A lot of people don’t even acknowledge me, like I’m not even here,” Shorty said. “Especially when you greet everyone … the least you can do is say hi or something. You don’t have to buy my paper, I don’t care. Say something.”