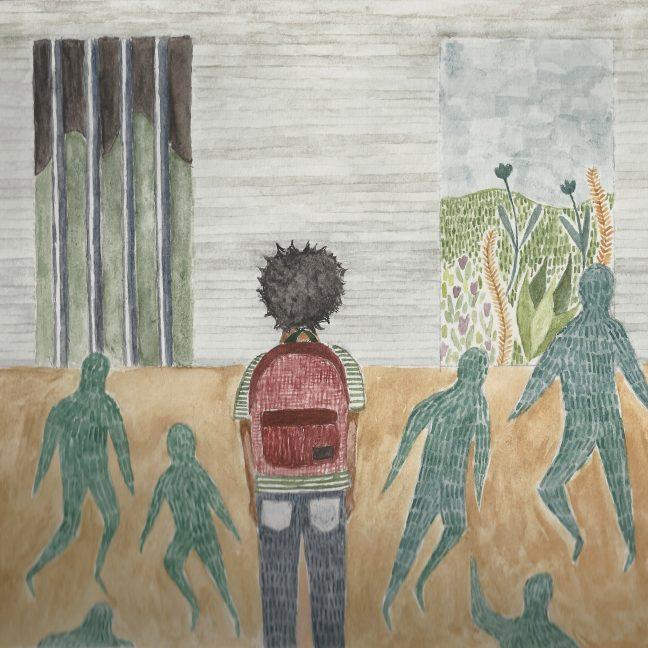

For most young people, the changes associated with coming of age can seem daunting, and when combined with the instability that comes with an arrest, it can become unmanageable. Restorative justice systems help youth stay away from a path of repeat offenses while introducing positive influences.

Restorative justice programs like the TimeBank’s Youth Court Program and the Dane County Community Restorative Courts work toward reshaping the traditional criminal justice model.

These programs allow victims and offenders to interact with one another and help repair the offender’s relationship with the community. In Dane County, the Community Restorative Courts act as an alternative to the judicial system for first-time offenders who are 17 to 25 years old.

Using funds from the Department of Children and Families, Madison has also expanded the reach of its youth peer courts in the past year. Any person between the ages of 12 and 16 who receives a municipal violation may now “opt-in” to one of the restorative justice courts run by the YWCA, Briarpatch or TimeBank.

Jonathan Scharrer, director of the Restorative Justice Project through the University of Wisconsin Law School, said restorative justice programs allow crime victims to get many of their lingering questions answered. These types of interactions decrease the victim’s fear toward the offender.

“When a serious offense occurs it dramatically impacts people’s lives in a way that is substantially altering from the day that it occurs, really, for the rest of their life,” Scharrer said.

In comparison to the traditional system, Scharrer said victims can feel better when given the chance to discuss how their lives may have changed from a crime. Before these discussions, most offenders do not have a full understanding of what their actions caused the victim to experience or how they impacted others in the community.

A community partnership

About two years ago, the Community Restorative Courts were established in South Madison as a pilot program. Today, the program has spread to not only the entire city of Madison, but to all of Dane County, dealing primarily with charges of simple battery, disorderly conduct, obstructing an officer, theft and community damage to property.

Ron Johnson, the coordinator for the program, said originally the charges were part of the pilot launch, but they intend to widen the charges as the program continues to grow.

Johnson said Dane County wanted to give the traditional justice system another tool to tackle the same issues through a different lens.

“We work with people that have been affected by the crime, the communities that have been affected, to help restore the balance,” Johnson said.

When a case is referred to the Community Restorative Courts, Johnson said there are no longer police, courts or a jury involved. The process involves the victim, the offender or respondent, Johnson and a group of community member volunteers called peacemakers, who go through a 16-hour training on restorative justice and policing.

Throughout the process, Johnson said the peacemakers speak to the respondent to learn about their background and who they are as a person outside of their case. The peacemakers help determine the proper action, whether that is an apology, community service or alternative assignment. Once completed, all charges and fines are dropped and the respondents are not put in the Circuit Court Access System, which is open to the public.

“We discuss not only the case, but who are you and what brought you to this point in your life,” Johnson said.

Preventing a cycle of arrests

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, within three years of release, about two-thirds of offenders were rearrested. Within five years of release about three-quarters of released convicts found themselves back behind bars. Restorative justice programs work to reduce these numbers through victim and offender dialogues and less punitive approaches sentencing for minor offences.

Scharrer said restorative justice programs help reduce recidivism and that there is a correlation to reduced crime severity if former participants in the program commit a crime again.

To date, there have been more than 60 participants in the Community Restorative Courts program. Only one person did not complete the program and two others chose to pay fines instead of joining the program. Johnson said examining the exact reoffense data of the participants is a 2017 project.

“We want to be able to hold the respondent accountable for what they did … but also provide them with support systems that will prevent them from reoffending,” Johnson said.

During the summer, the controversial arrest of Genele Laird at East Towne Mall sparked a renewed conversation on the restorative courts after a video of her arrest went viral.

Though her case was originally ineligible, the District Attorney Ismael Ozanne decided to transfer her to the program. Ozanne said for Laird, it gave her a chance to reduce her risk to reoffend. To have her charges fully lifted, she needed to complete all the terms of the program.

But Laird’s arrest met criticism from activists like Alix Shabazz, a member of Freedom, Inc., who said Laird’s referral to the restorative justice program was not enough to address unequal treatment of black citizens. Many said Laird shouldn’t have been arrested in the first place.

Community members gather at East Towne Mall to protest Genele Laird arrest

Expanding the reach of youth courts

According to an internal progress report, 81 percent of people between the ages of 12 and 17 were referred to the Municipal Diversion Program youth courts. Of that 81 percent, 70 percent successfully complete all portions of their agreement. Those who do not must go through the traditional juvenile justice process.

Youth courts are unique from other restorative justice methods in that they involve youth of the same age to come up with a plan appropriate to each case. Kris Moelter, a program facilitator and former criminal attorney, said the process requires only minor support from adult coordinators who occasionally step in during the informal proceedings and to offer advice when the young jurors deliberate.

The restorative plan for each offender is tailored to meet their specific needs and take advantage of their interests, Moelter said. Lorrie Hurckes, Executive Director of the Dane County TimeBank, said this allows kids to get involved with something positive while also fostering a positive relationship with a member of the community.

“If someone is interested in becoming a lawyer they may have to do a bit of mentoring with a lawyer in the TimeBank,” Hurckes said. “If someone is interested in music they might have to do a few music lessons through the TimeBank as one component of their agreement.”

A central component of many of these agreements is the community-embedded exchange system created by the TimeBank itself. The nonprofit offers a way for community members to exchange goods and services with each other using service hours instead of money. The system is free and serves to bring community members closer together.

The system further entwines the community with peer courts while also incentivizing jurors to take part in the system since they receive hours for hearing cases. Hurckes said the system also benefits from a host of community members and organizations that are always interested in employing or working with young people.

“The idea is you help your community, your community helps you,” Hurckes said.

Even though cases the peer courts hear can include charges of stealing, fighting, drug use and vandalism, Moelter said the students and youth she deals with are pretty well-behaved. Often, Moelter said the incidents in question are simply mistakes which any teenager might make and she rarely encounters a student reoffending after an agreement is reached and completed.

Local officials announce program to reduce disparities in criminal justice system

Moelter, who has worked in restorative justice courts since 1999 in and outside of Dane County, said she is continually impressed by the maturity and insight jurors show. Still, she is working with teenagers, so she said she’s learned to be flexible.

“I’m pretty much just there to facilitate … sometimes I can help by asking questions but that’s rare,” Moelter said.

While the program has been successful for the most part, the report also outlined several areas for improvement. Not all officers communicate the restorative justice option to offenders when issuing tickets and staffers encountered difficulty contacting youth who went through the process.

Restorative justice and racial equity

Programs such as these also aim to curb the negative impact of the juvenile justice system on communities of color by offering alternatives to traditional punitive sentences. According to Madison Police Department data, 75 percent of the 861 municipal citations issued to those ages 12 to 16 in 2014 were to people of color.

In September 2015, Dane County Criminal Justice Workgroups were asked to make recommendations to improve the criminal justice system in a resolution focused on racial disparities and mental health challenges in the jail. One of the suggestions was expanding restorative justice as an alternative to incarceration.

Latest Dane County work group to address racial disparities in jail diversion programs

Before the report came out, the Wisconsin State Journal found black people were arrested at a rate more than 10 times higher than white people. One of the goals of restorative justice is to eliminate racial disparities within the criminal justice system.

Scharrer said in restorative justice some of the disparities fade away when people are looked at holistically, through a more complete picture of the person’s background and factors that led to the crime.

“When we look at this person in a more complete picture you can help, hopefully help, eliminate some of the implicit bias or some of the bias of the traditional system,” Scharrer said. “Some of those disparities tend to fall away when you look at people as people.”