“Mithila Painting: The Evolution of an Art Form” is an eclectic, captivating exhibit that dives headfirst into the culture of Bihar, one of the poorest states in India. The collection, which is located in the Leslie and Johanna Garfield Gallery at the Chazen Museum of Art, is open to the public until Dec. 1 and is far from an ordinary art exhibit. An inherent appreciation of culture resonates through each piece, whether the artist sought to remain within the confines of his or her community’s customs or redefine expectations with displays of social commentary.

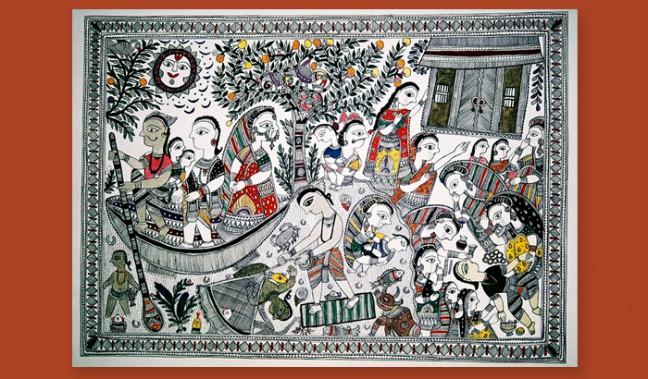

Mithila painting has evolved as a tradition that started about 700 years ago, with women using flower pigments and bamboo to adorn walls with religious motifs and wedding décor. The themes of the Mithila paintings, which have now expanded dramatically, alter by caste and community; even the materials used are selective based on the community. Yet the level of detail in each of the paintings doesn’t change, the colors are characteristically bold and alive and the spaces are all overflowing with increasingly textured patterns. Pages are splattered with flowers, trees, underwater spirits, snakes, almond eyes and indifferent, straight faces. The paintings are less about the subjects and more about how they fit into their surroundings, into nature; it is as if the artist is catching the scene just a moment before the subjects can react.

A vibrant piece called “Women Watering Krishna’s Kadam Tree,” by artist Sangita Kumari Bhagat, shows two women feeding water to a tree that represents the god Krishna. Awkwardly-shaped triangles perfectly illuminate the tree’s curvature, forming geometric abstractions that come off as intelligent products of a pensive artist. The branches of the tree shoot out in all directions, hundreds of leaves delicately mapped out to reach all the empty spaces. As the eyes are drawn vertically up the branches, the tree seems to slip off the page, leaving the imagination to decipher the larger image.

The Mithila artists seem to have a strong connection to the idea of snakes. Snakes are referred to as naga, and it’s difficult to tell whether they represent an evil or benevolent force, or perhaps both. In the more modern section of the exhibit, which focuses on political and social issues in both Bihar and India as a whole, a piece titled “Radiant yet Submissive” by Shalinee Kumari uses snakes to symbolize the men in a woman’s life. The female subject of the piece is split into two alter egos: The first radiating waves of light on the left, and the other nodding submissively to a pack of snakes on the right. This painting is the first of many that provides surprisingly explicit social commentary. One titled “From Marriage to Bride Burning” touches on the polemical problem of acid-burning in India. The painting, which is set up as a six-scene narrative, seems relatively harmless at first glance, like an extended form of the kohbar. It becomes shocking when the viewer catches the last scene of the husband dumping kerosene on his bride while the mother-in-law strikes the match.

Other paintings in the second part of the exhibit quickly estrange themselves from the initial, harmless motifs of fishes, trees and domestic rituals. The paintings become more and more thematically heavy, touching on issues of abortion of female babies, 9/11 and HIV. The style stays the same throughout; thank goodness for that, because each piece is like a maze that’s just too perfectly complex to step away from. At times, the paintings providing social commentary try a little too hard to make a point. “Creative Destruction: The Benefits and Costs of Capitalism” displays three symbolic figures, one of which sports an overloaded truck as a hat. This comes off a little bit more silly than intended. However, what sticks with the viewer most is the dedication, the attention and skill that goes into each piece. Mithila paintings pulse with color and life, and the pieces are fascinating regardless of the subject matter.