When a university makes the decision to cut a sport, part of the school’s soul is lost with it. It is a decision that has become all too common as a result of COVID-19 financial complications.

Both the University of Iowa and the University of Minnesota have made the decision to cut some sports programs following the Aug. 11 announcement by the Big Ten Conference that football would be postponed. Iowa dropped men’s gymnastics, men’s tennis, and men’s and women’s swimming after estimating $100 million in revenue would be lost. In the same vein, Minnesota cut men’s gymnastics, men’s tennis, and men’s track and field.

Since the reinstatement of football Sept. 16 — and with it the return of at least $50 million in TV deal revenue — neither school has restored the programs dropped or the jobs lost. Iowa Athletic Director Gary Barta made it clear that the school had no intention of restoring any of the lost teams, stating that it simply “isn’t possible.”

Minnesota took a similar position, not reinstating any of the sports lost despite the financial benefit the return of fall football entails.

The question for these universities and the Big Ten Conference — where did the money go? What happened to the near $700 million from the Big Ten Network-Fox Sports joint TV deal? Or the $440 million yearly compensation from CBS as part of a six year/$2.64 billion contact? Why can’t endowment laws be restructured to preserve the integrity of “amateur” athletics? Why are schools just now closing programs that have historically operated at a massive loss anyway?

Both schools report that losses are likely to be within the $40 to $60 million range even after the decision to play football. But the costs of athletic departments are consistently overestimated and revenue underestimated, according to the Washington Post.

Economic theorists have provided helpful insight into understanding why losses are often overcalculated and revenues undercalculated. Everything from merchandising profits to scholarship costs to construction fees makes the accounting of college athletics notoriously messy.

Merchandising revenue is often understated on the bottom line because it is first distributed to other departments within the university before it reaches an athletic department’s balance sheet. Additionally, OSKR economist Andy Schwarz explains that unless giving an athlete a scholarship prevents another student from paying tuition, the dollar amount of the scholarship isn’t actually lost by the school. But it can be stated on a balance sheet as an expense. Out-of-state tuition waivers, Title-IX tuition waivers, lottery funds and a bunch of other technical terms inflate the actual value of the cost of running an athletic program.

Schwarz wrote on Deadspin.com in 2014 that if the goal of a university is to increase enrollment, as has empirically been the case at many of the Big Ten’s large state schools, the actual cost of scholarships may be “pennies (or at least dimes) on the dollar of the listed cost.”

These baffling numbers and strategies beg the question of why athletic departments cut sports in the first place. In 2013, Temple University saw key recruiting losses across a variety of sports, primarily as a result of the athletic department’s inability to provide full scholarship packages. In early 2014, the school cut seven sports and increased funding for the remainder of the athletic department. Effectively, the school fired 162 student-athletes to consolidate losses after a disappointing football season.

Recent memory also recalls the University of Alabama-Birmingham cutting football, bowling and archery in 2014, though the latter two of the sports were operating at a profit. In a 110-page report published by OSKR and written by Daniel Rascher alongside Schwarz, the economists found that costs at UAB were overstated, revenues were understated and being part of Conference USA for football was extremely financially advantageous for the school.

Outside of the monetary benefits these programs experience within the athletic department, Rascher and Schwarz found that these sports correlated to an increase in applications, enrollment, quality student life and exposure of the school.

The decision to cut sports that have proven their value to the university has rationale analogous to Temple’s decision, just on a larger scale. The popular conspiratorial belief is that the Alabama Board of Trustees, which governs all University of Alabama system schools, pulled the plug on UAB football in a move to divert funds toward the capstone University of Alabama-Tuscaloosa program. Additionally, the movement to bring back UAB football — which returned to the gridiron in 2017 and reached bowl games in each of the past three seasons — generated $20 million dollars that otherwise would not have ended up in the coffers of UAB President Ray Watts.

Conclusion — schools cut sports to cut their losses and invest in more competitive programs.

Ohio University associate professor of sports business, B. David Ridpath, told My Central Jersey in May, “I think dropping sports is basically a knee-jerk reaction and many of the schools are using the pandemic as an excuse for something they already wanted to do.”

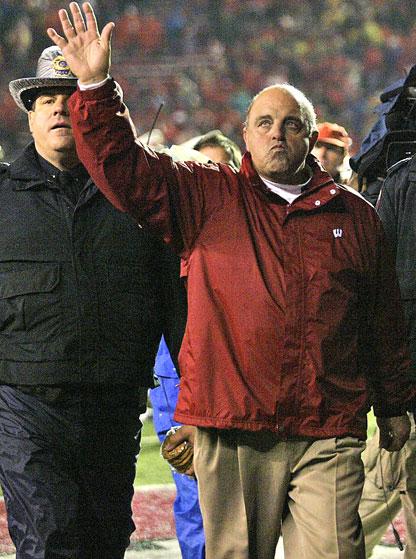

For the Badgers, neither University of Wisconsin Chancellor Rebecca Blank nor Athletic Director Barry Alvarez have announced plans to cut any fall sports, which include football, women’s volleyball, men’s and women’s cross country and men’s and women’s soccer.

That is, unless student-athletes start getting paid. In September 2018, in regards to a federal bench trial summons, Blank testified, “It’s not clear that we would continue to run an athletic program” if the NCAA was required to compensate student-athletes.

As damage control, UW released a statement later that week indicating that college athletics would continue to be offered. Blank would not return to testify whether or not she had co-signed the statement from the university.

In May, the top 25 earners in UW Athletics voluntarily chose to take a 15% pay cut until November. Blank has pledged to take a 15% pay cut from her $590,000 salary until November as well. Big Ten football will be entering its third week by then and Big Ten men’s basketball will be just three weeks away. Additionally, Wisconsin’s sustained success and relevancy in football, men’s basketball, and men’s and women’s hockey gives UW a bit of a cushion when hit by unforeseen economic circumstances.

In the short term, there are no immediate signs that UW will cut any fall sports in 2020.